Primary Source Set - Franklin Leavitt Maps

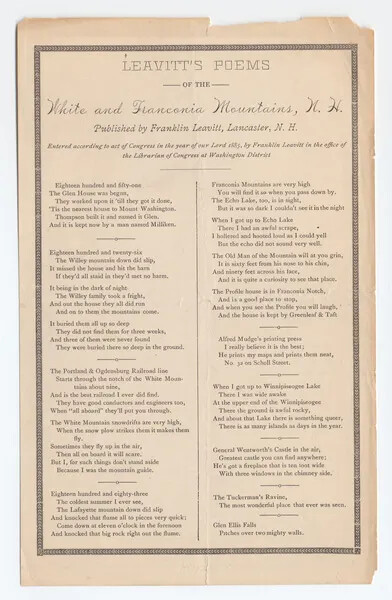

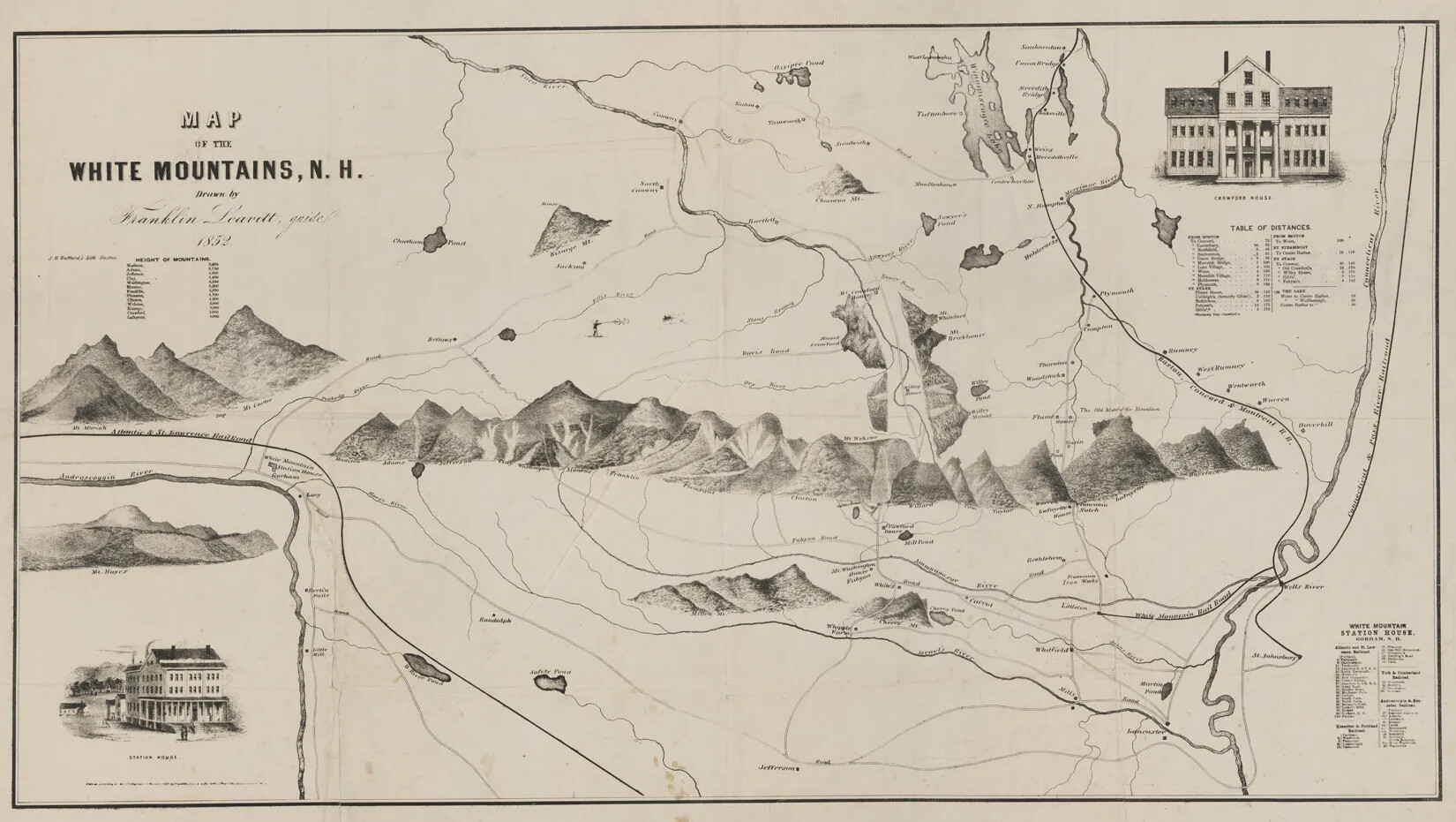

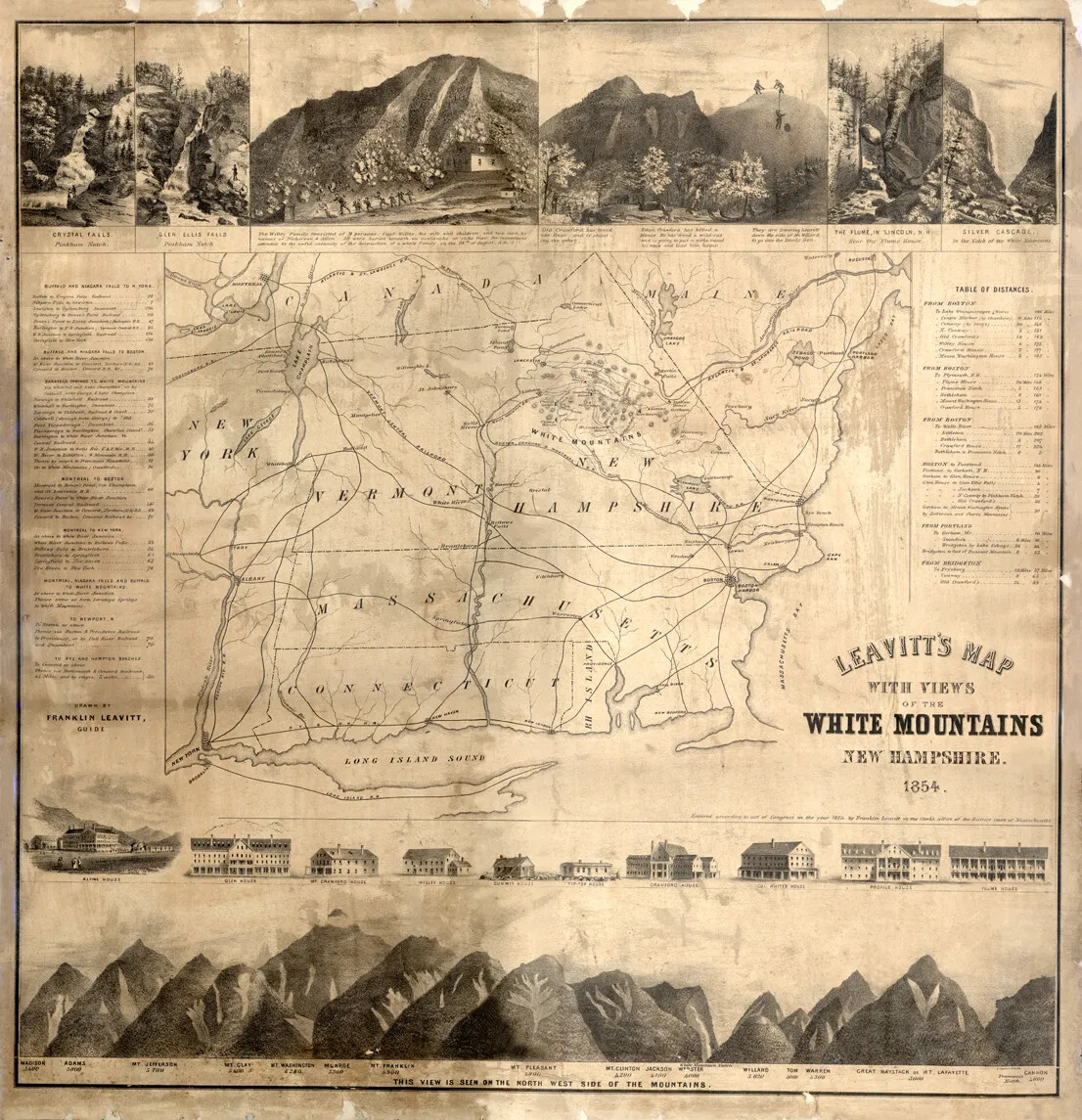

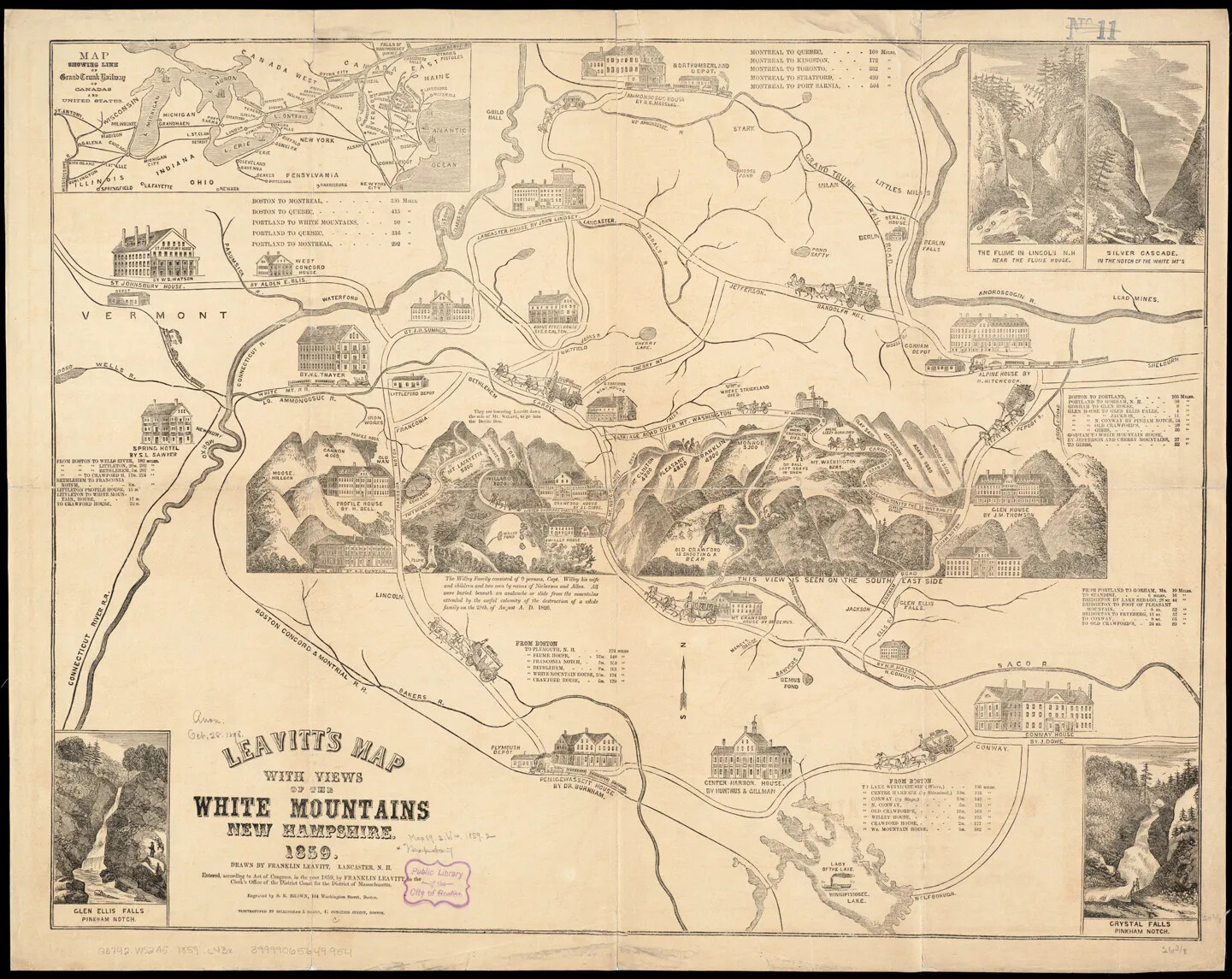

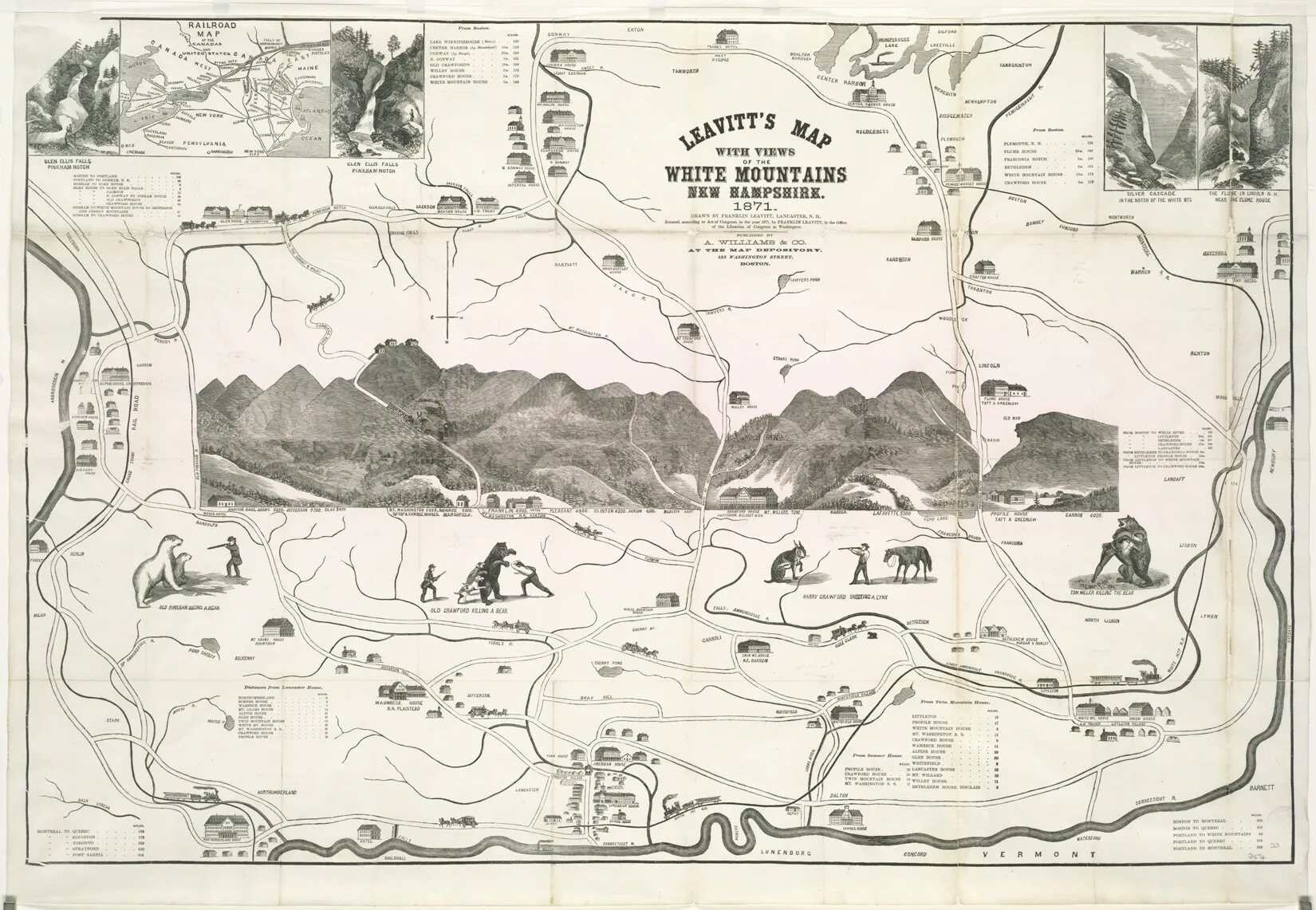

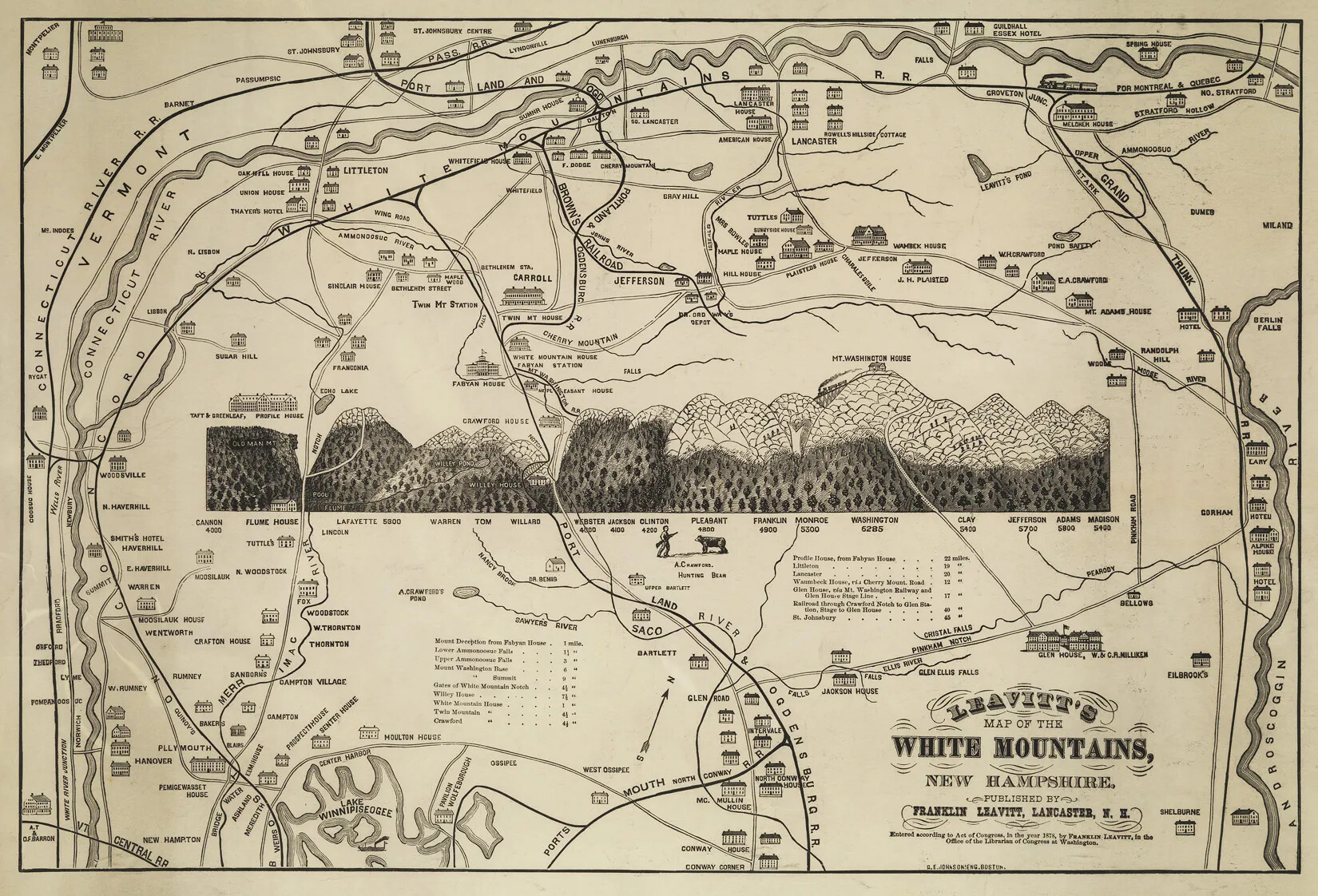

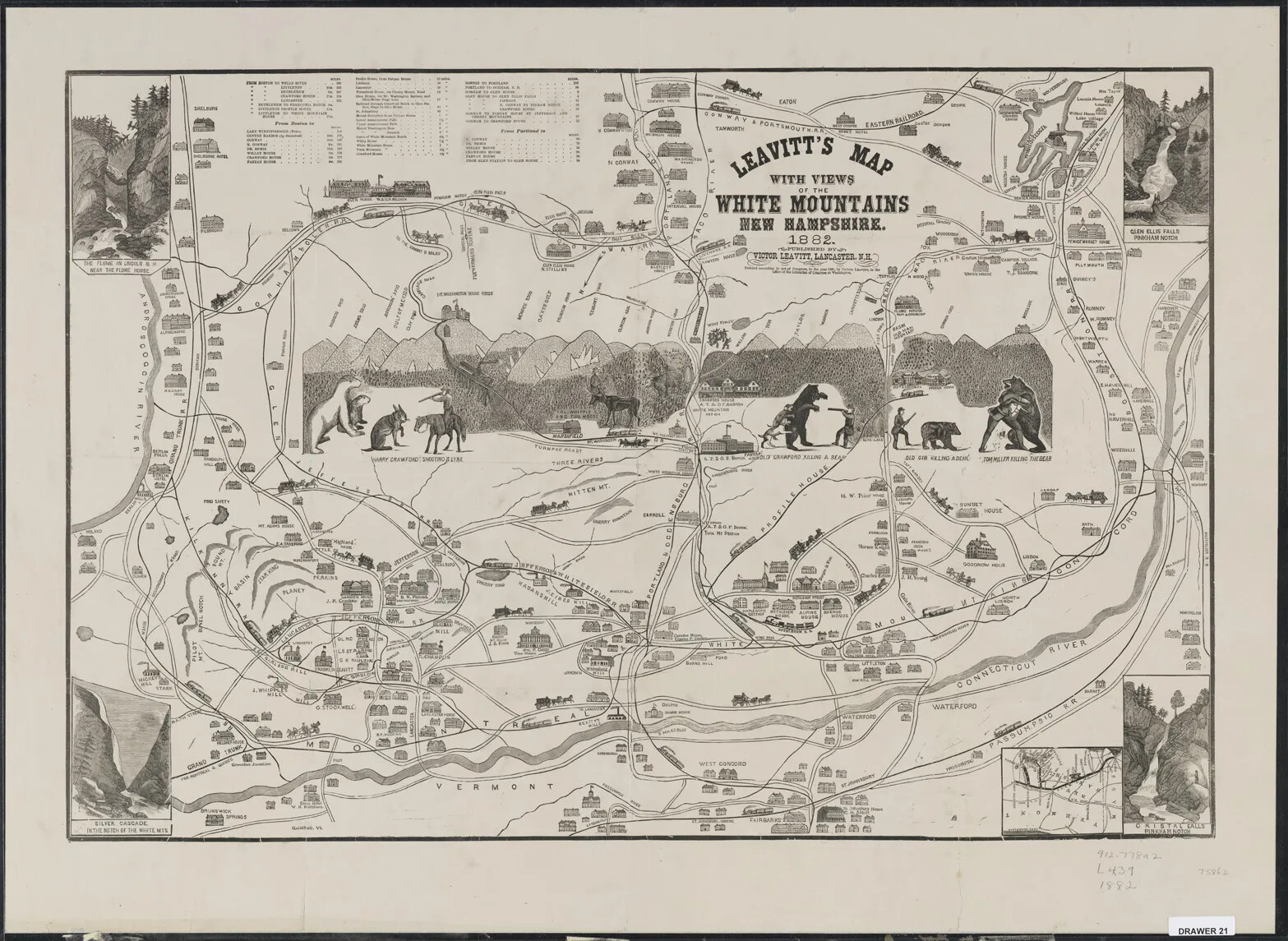

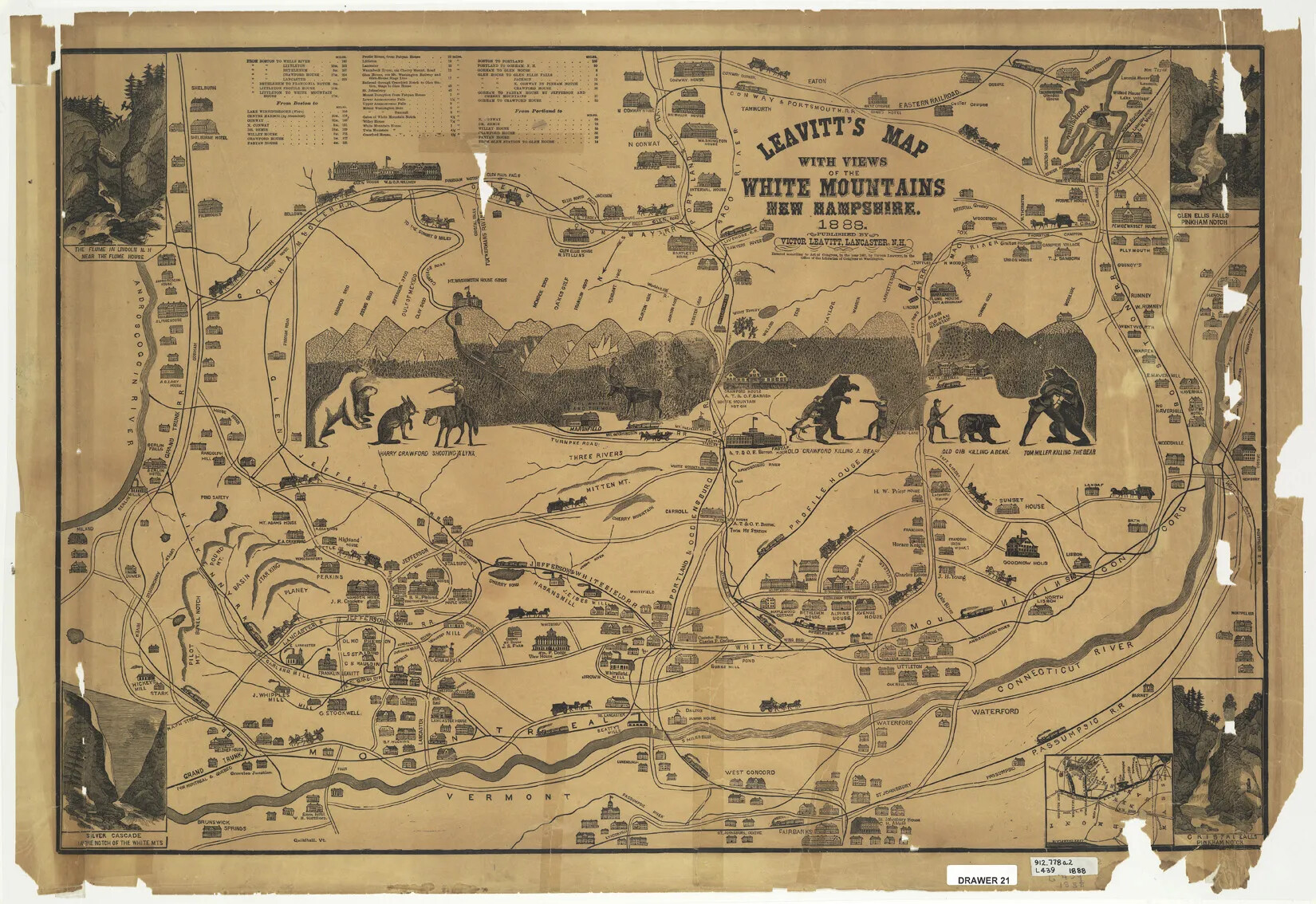

Franklin Leavitt created a series of eight maps of the White Mountains in the 19th century that captured the history of the region, promoted tourist destinations, and offered whimsical depictions of the White Mountains that contributed to the area’s legends and lure.

Background

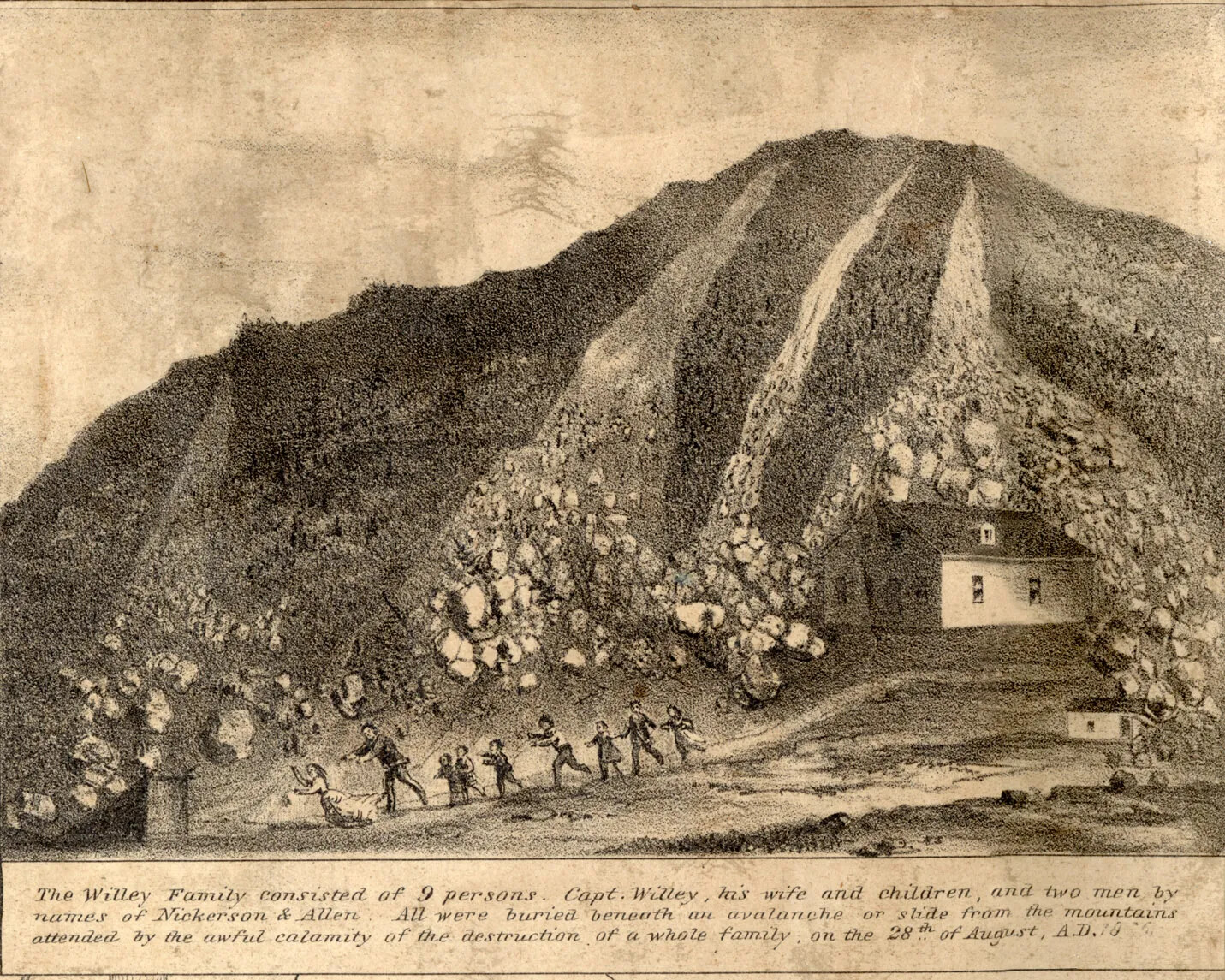

The maps were “cartographically ludicrous”—nothing was drawn to scale, noted landmarks were shown out of position, and the geographic orientation had almost no relation to reality. The first of the series was flipped, with north being shown at the bottom of the map and south at the top. Later versions were more conventionally oriented. But through drawings, poetry, and small vignettes, Leavitt’s maps created a mythology about the White Mountains. The maps related stories such as the Willey tragedy and established regional heroes, like Abel and Ethan Allen Crawford, who are depicted as larger-than-life figures wrestling bears and subduing various forms of wildlife.

Born and raised in Lancaster where he was a farmer, Leavitt became a well-known White Mountain figure in the middle of the 19th century. He had worked at the famed Notch House, one of the earliest White Mountain inns, where many tourists stayed during these years. He had helped build mountain trails, carved popular wooden souvenirs, and gained renown as a storyteller and guide. Later in life, he would help build the carriage road to the summit of Mount Washington and try his hand at writing poetry. In many of these endeavors, he showed a talent for self-promotion.

In 1852, Leavitt produced the first of his tourist maps, although it had an even greater significance than that. That map was the first map of any kind depicting the White Mountain region, and although other, more serious maps would quickly follow, it blazed a trail in New Hampshire mapmaking for this reason alone.

Other maps followed in 1854, 1859, 1871, 1876, 1878, 1882, and 1888. Through the progression of these maps, viewers are given a snapshot of the expansion of infrastructure in the White Mountains, much of it pertaining to tourism with the construction of hotels and railroad lines, the development of roads and hiking trails, and the identification of tourist sites. Each version of the map becomes more and more complicated, in part because of the development of the area, but also because Leavitt himself added storytelling elements to the maps.

All of the maps are fine examples of 19th-century folk art, hand-drawn by Leavitt himself. He took each map to a Boston printer to turn them into engravings that were then sold and widely distributed. Leavitt’s maps were among the most popular 19th-century souvenirs, and as such they ended up all over the country when tourists took them home. But since they were made out of paper, not many of them survive today.

This primary source set guide can be used in several ways to explore the Franklin Leavitt maps. It is not necessary to use all sources in a set to create a meaningful inquiry. Rather, educators are encouraged to select—or have their students select—the sources best suited to your project.

Additional Resources

- Georgia Brady Barnhill, “Depictions of the White Mountains in the Popular Press,” Historical New Hampshire 54, Nos. 2 & 3 (Fall–Winter 1999): 107–23.

- David Tatham, “The Iconography of the Early White Mountain Resort Hotels, 1825–1875: Prints, Photographs, and Maps,” Historical New Hampshire 50, Nos.1 & 2 (Spring–Summer 1995): 66–79.

Focus Questions

In addition to our general suggestions for using primary source sets, consider giving students one of the following prompts for an inquiry using this primary source set about the Franklin Leavitt maps.

-

1How would a tourist’s visit to the White Mountains in 1852 be different from a tourist’s visit in 1888?

-

2How did Franklin Leavitt tell stories through his maps?