Primary Source Set - Amoskeag Manufacturing Company

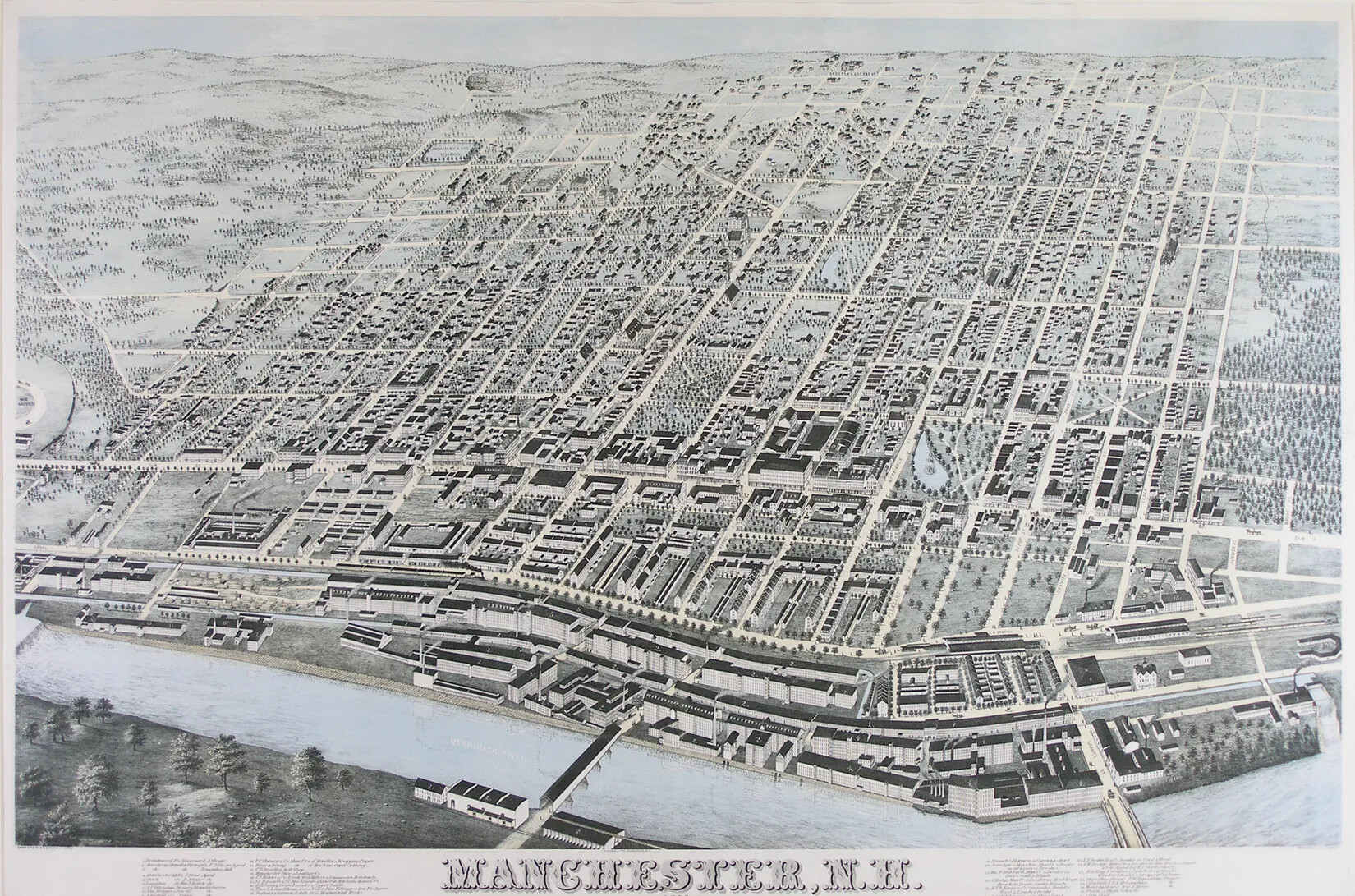

Once the largest textile mill in the world, the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company dominated the textile industry in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was one of the great industrial giants of its day, and its impact on New Hampshire’s development was profound. The company made Manchester the largest city in both New Hampshire and northern New England, a distinction the city still holds today even decades after the Amoskeag mills closed.

Background

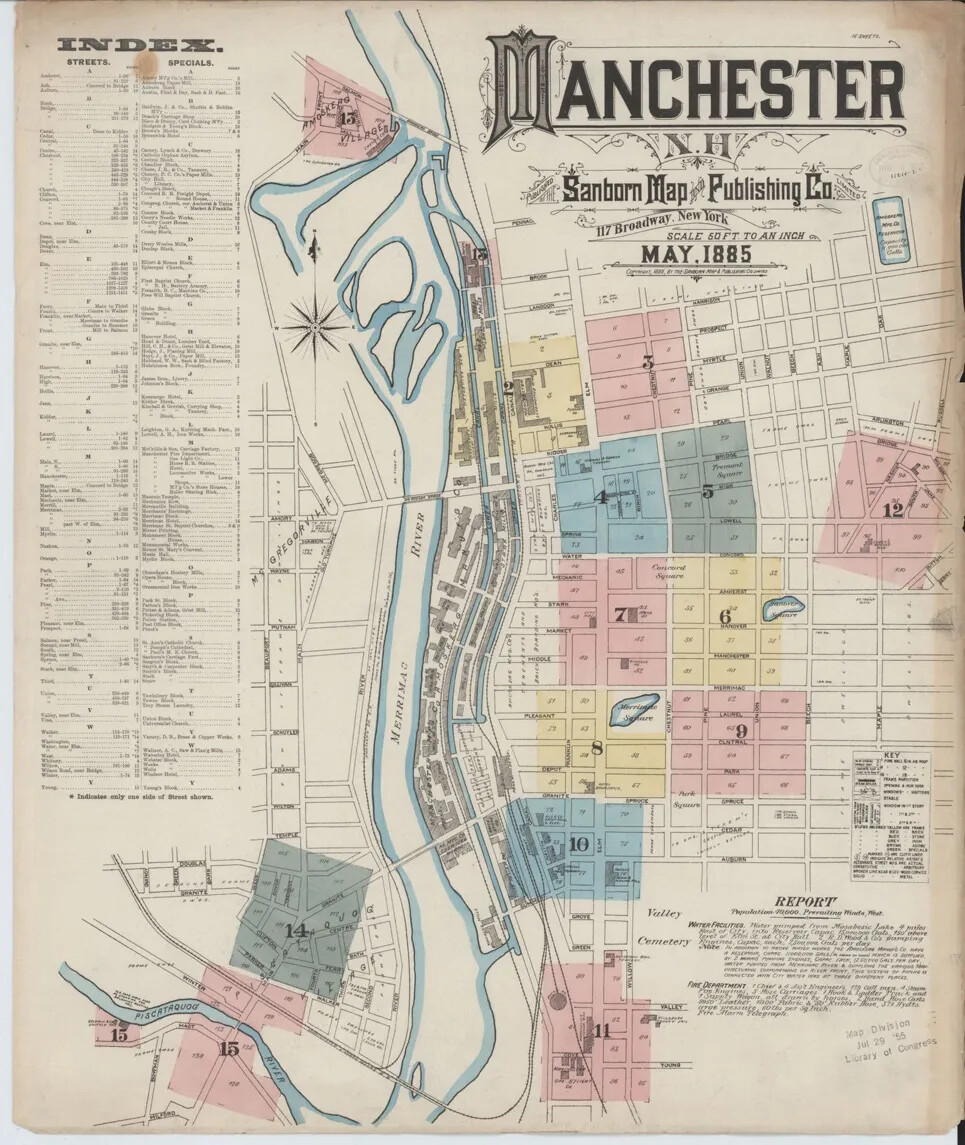

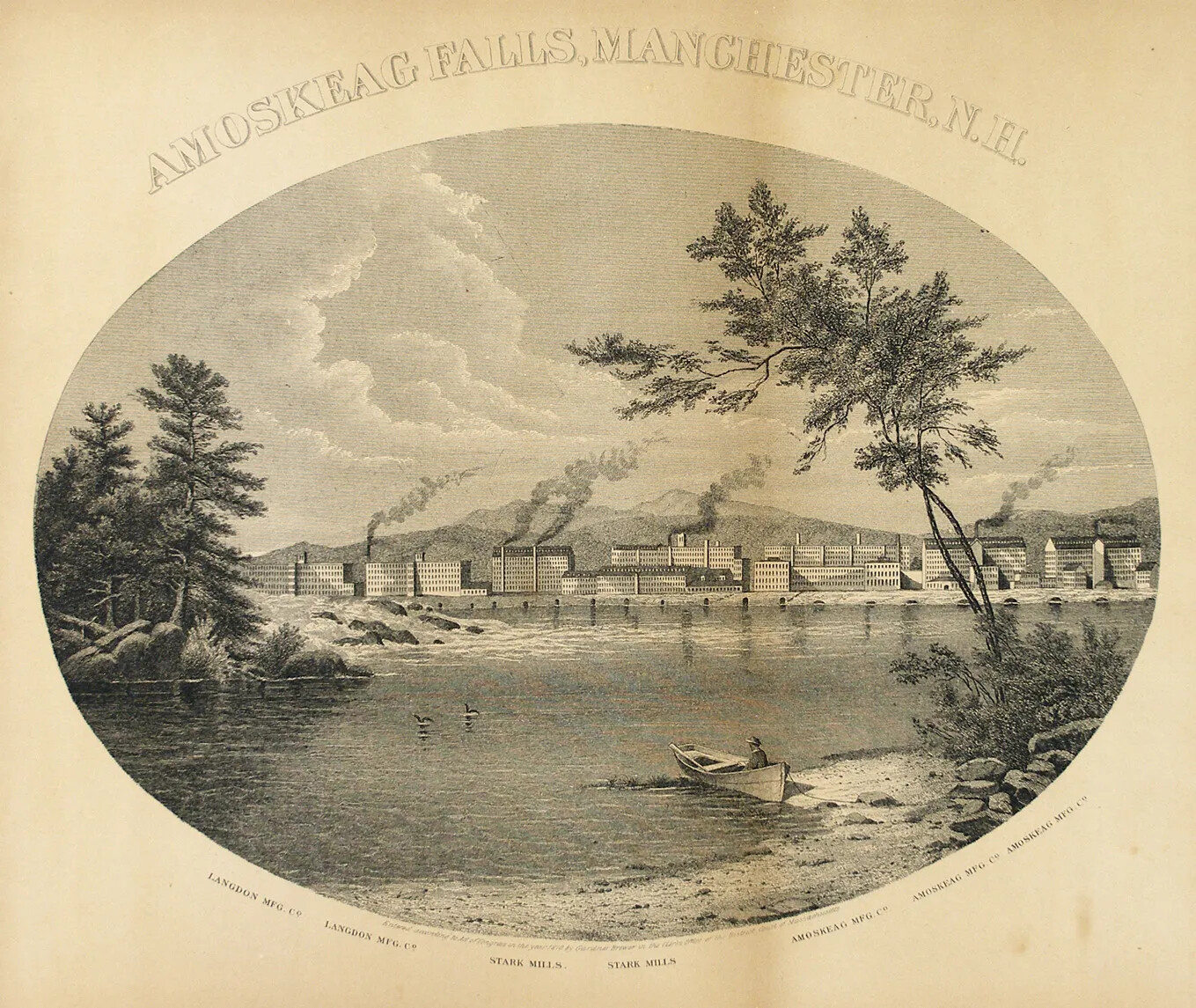

Manchester began as a small farming village located several miles east of the Merrimack River. It was originally called Derryfield. The town’s potential as an industrial center was first recognized by Samuel Blodget, local businessman, inventor, and entrepreneur who built a canal-and-lock system on the Merrimack River near the Amoskeag Falls. When Blodget’s canal system opened in 1807, it allowed boats travelling between Concord and Nashua to bypass the steep falls completely, thereby providing for water travel north of the falls, which opened this area of the state to development. At that time, water travel was the most efficient way to transport goods and people, so the navigability of the Merrimack, the largest river in central New Hampshire, was of prime importance. Within a few years, through the construction of other canals and locks, the Merrimack would link Concord to Boston, opening up for central New Hampshire all sorts of possibilities for trade and industry.

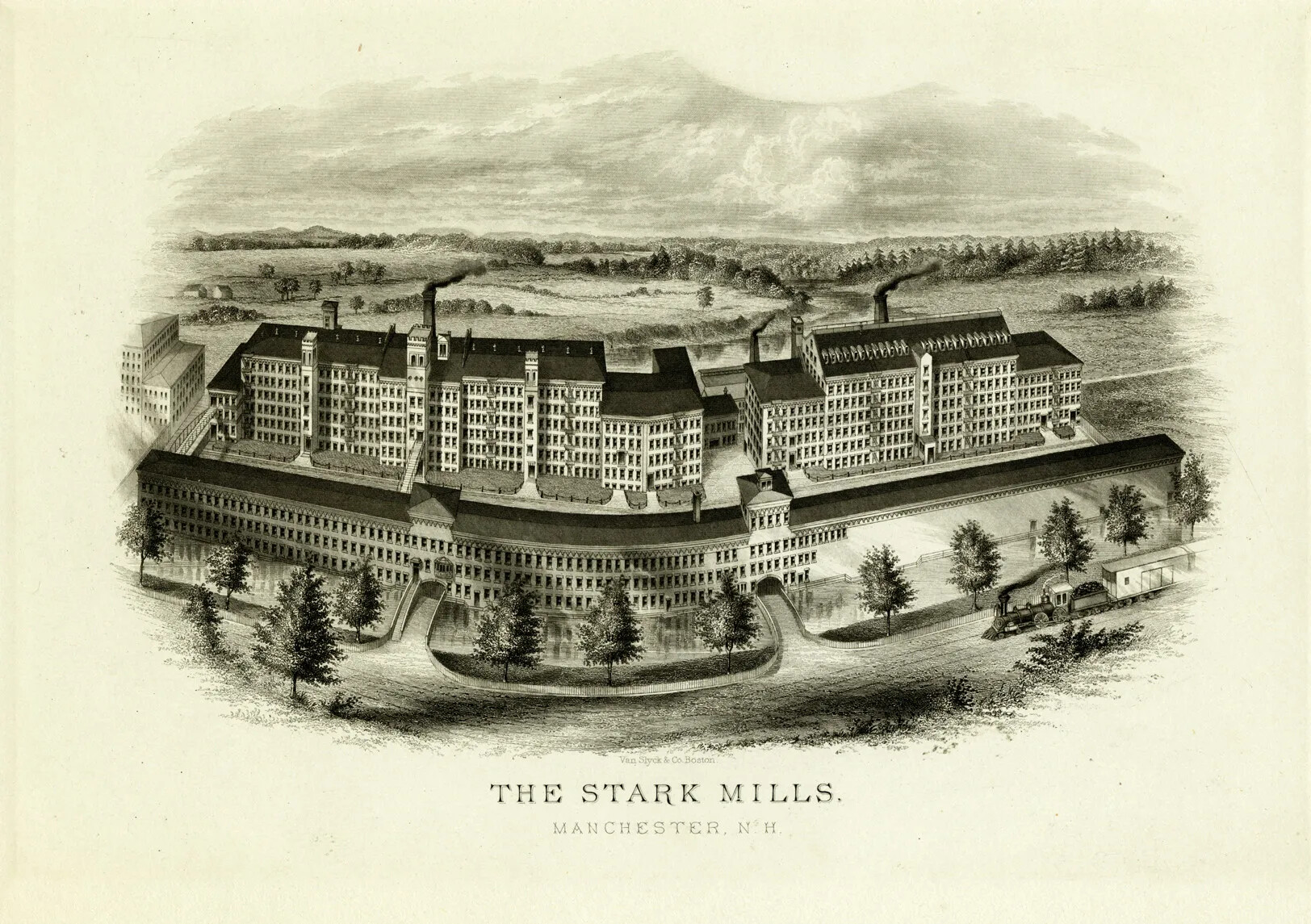

Blodget envisioned the creation of a massive factory complex on the banks of the Merrimack, as he was intrigued by the developments in mechanization that had turned England into an industrial leader and were just starting to appear in the United States. He proclaimed that the spot around the Amoskeag Falls would someday become the “Manchester of America,” a water-powered textile center comparable to Manchester, England. While Blodget did not live to see his vision of an industrial complex realized, the town of Derryfield voted to change its name to Manchester in 1810, as a memorial to Blodget’s dream.

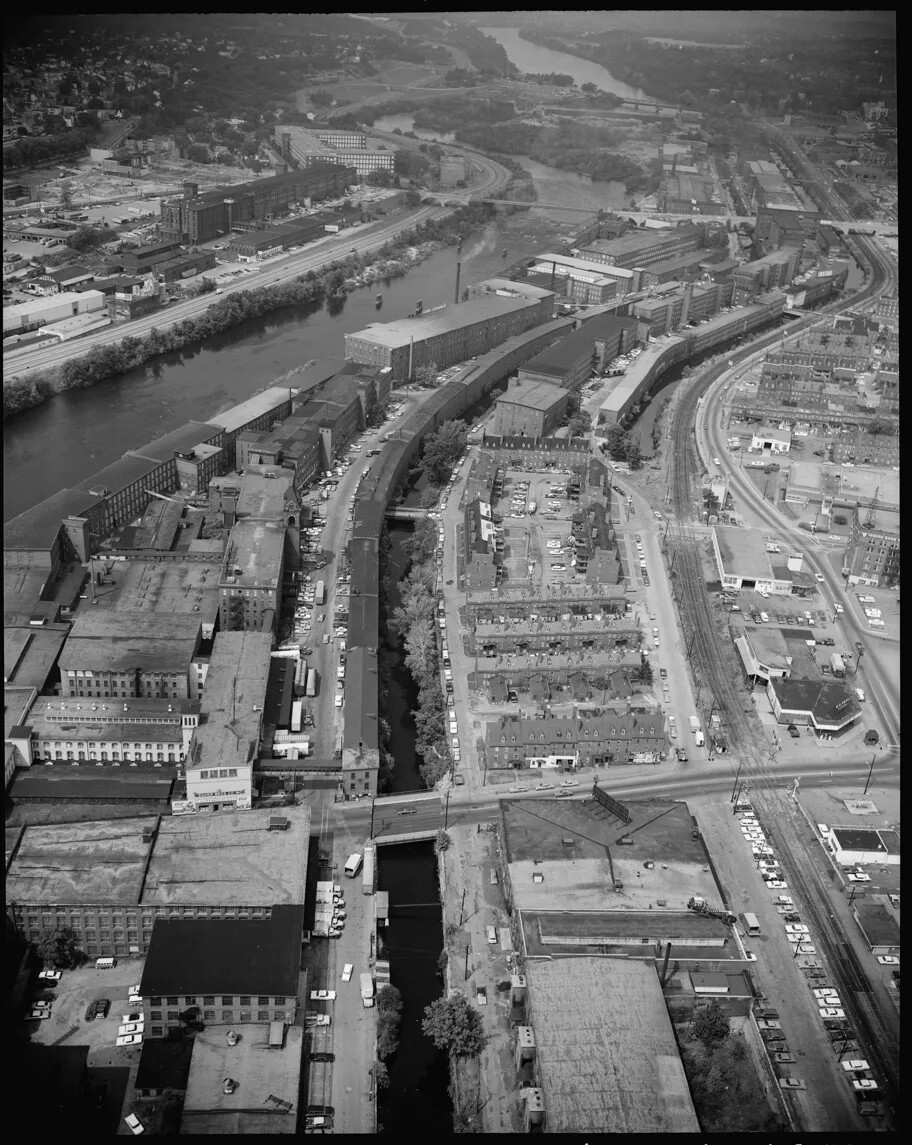

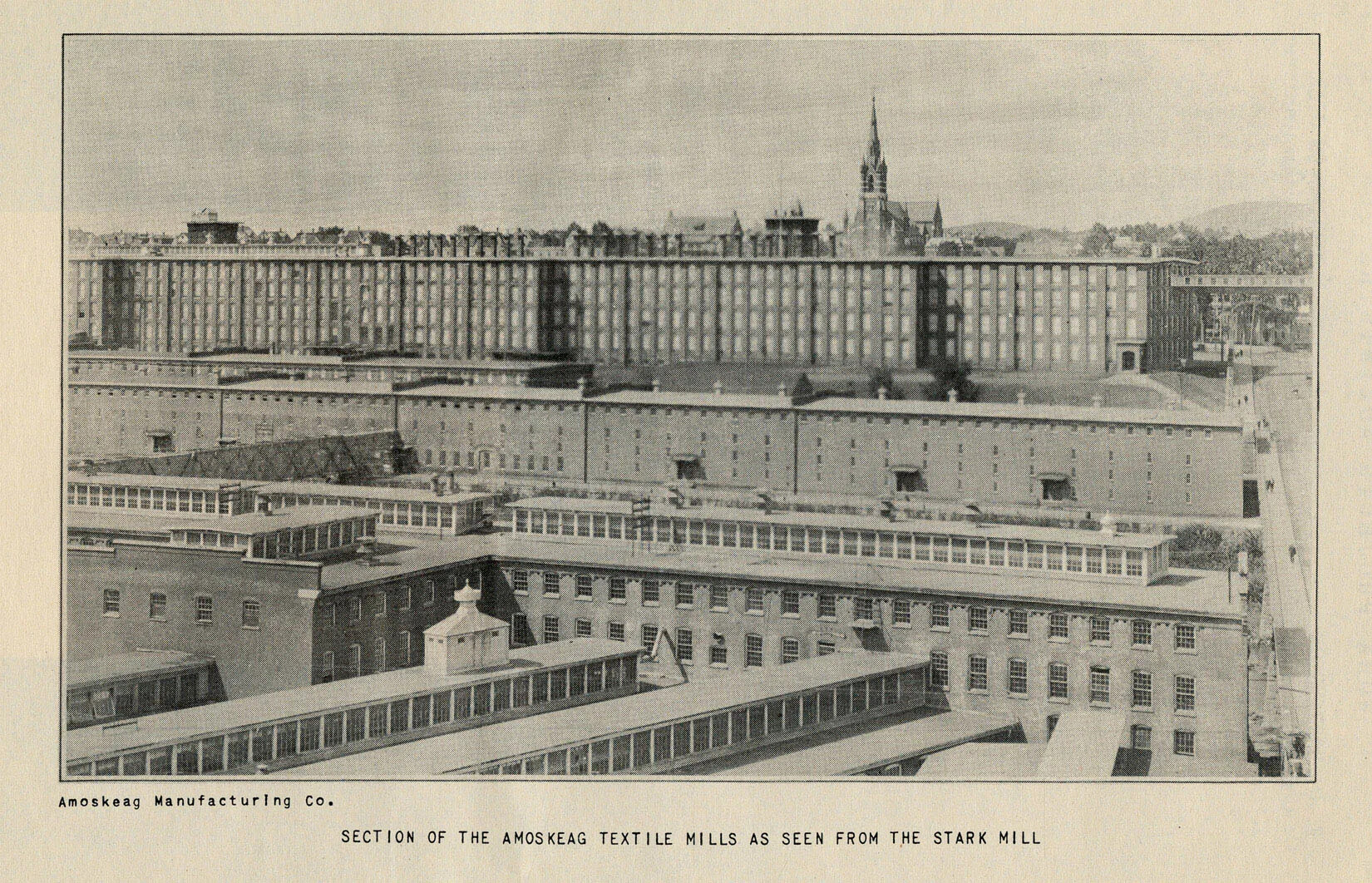

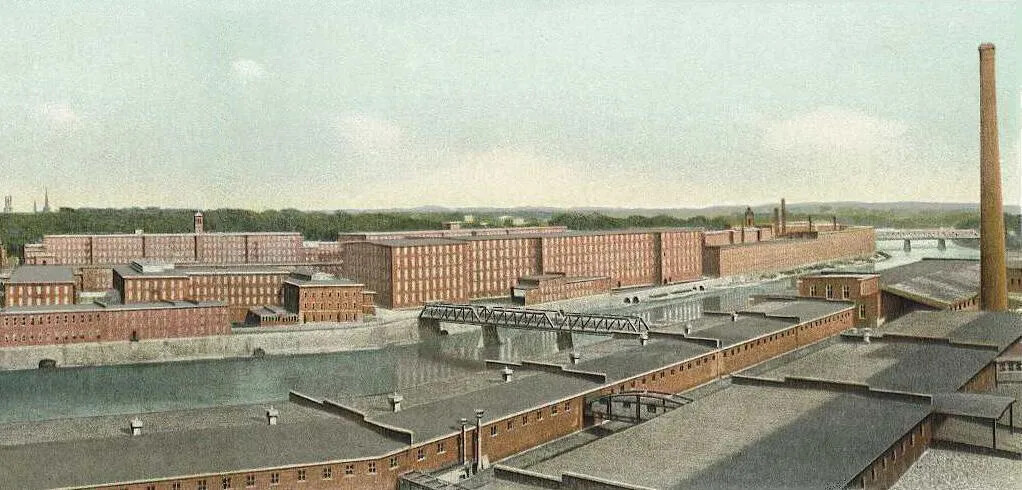

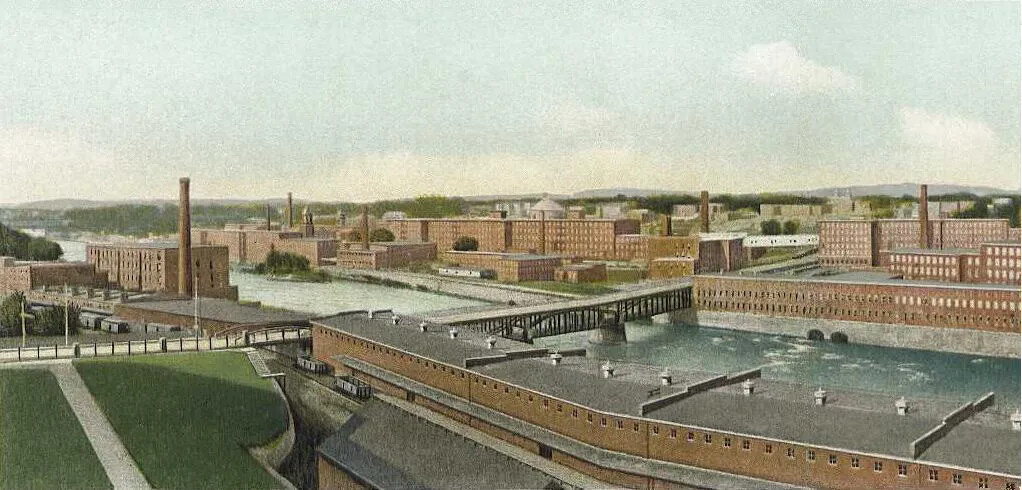

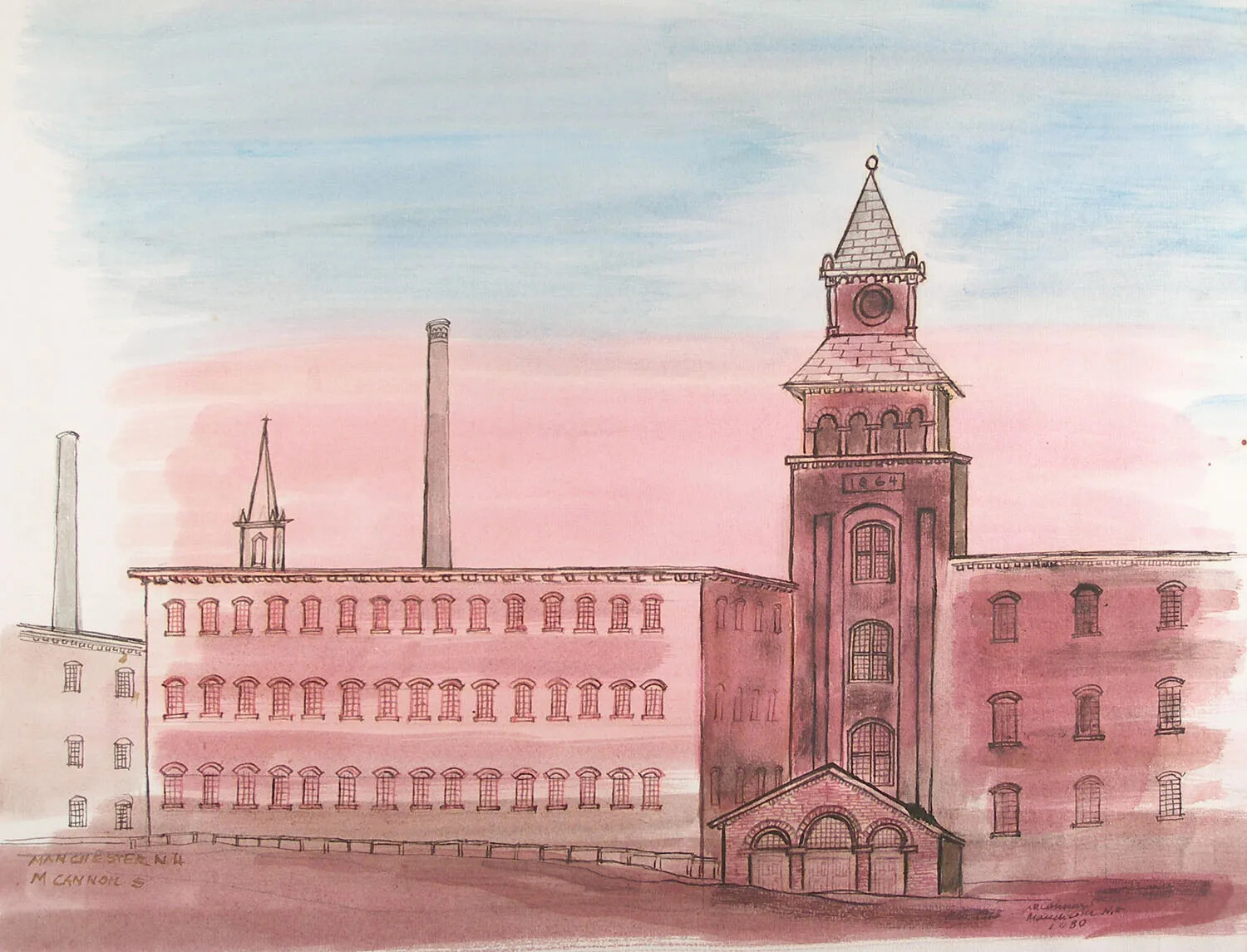

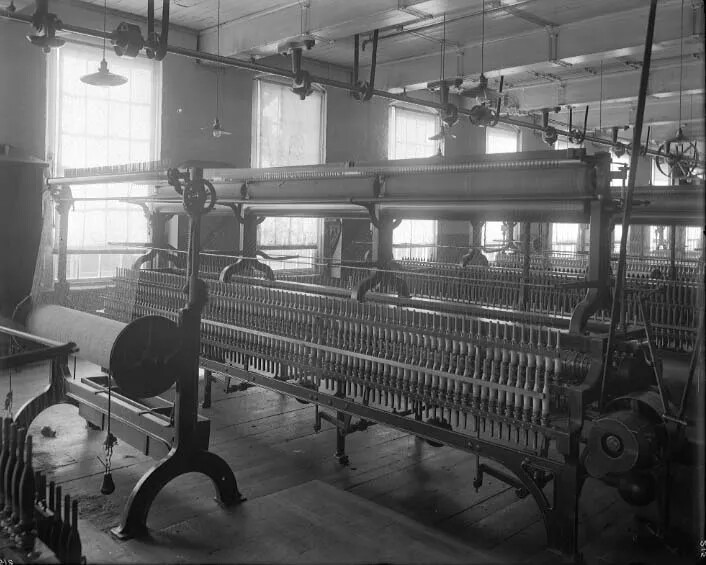

Inspired by Blodget’s successes and the power of the Merrimack River, a group of men led by Benjamin Prichard established the Amoskeag Cotton and Woolen Manufacturing Company, the precursor to the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company, in 1814. The first structure of this mill was actually on the opposite banks of the Merrimack from Manchester in land that was owned by Goffstown at the time. As production grew, so too did the need to expand the company’s physical footprint, and buildings spread to the islands in the Merrimack and onto the east side of the river. The company imported new technologies from England that allowed the process of generating textiles to become more and more mechanized and encouraged further growth. Nevertheless, the Amoskeag Company floundered in these early years. It was only after the faltering business had been bought out by a group of Boston investors in 1830 that it began its meteoric rise, fueled by a a massive investment of Massachusetts capital. Between 1838 and 1915, the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company constructed a total of 40 mill buildings, a dozen or so of which still stand in the city today.

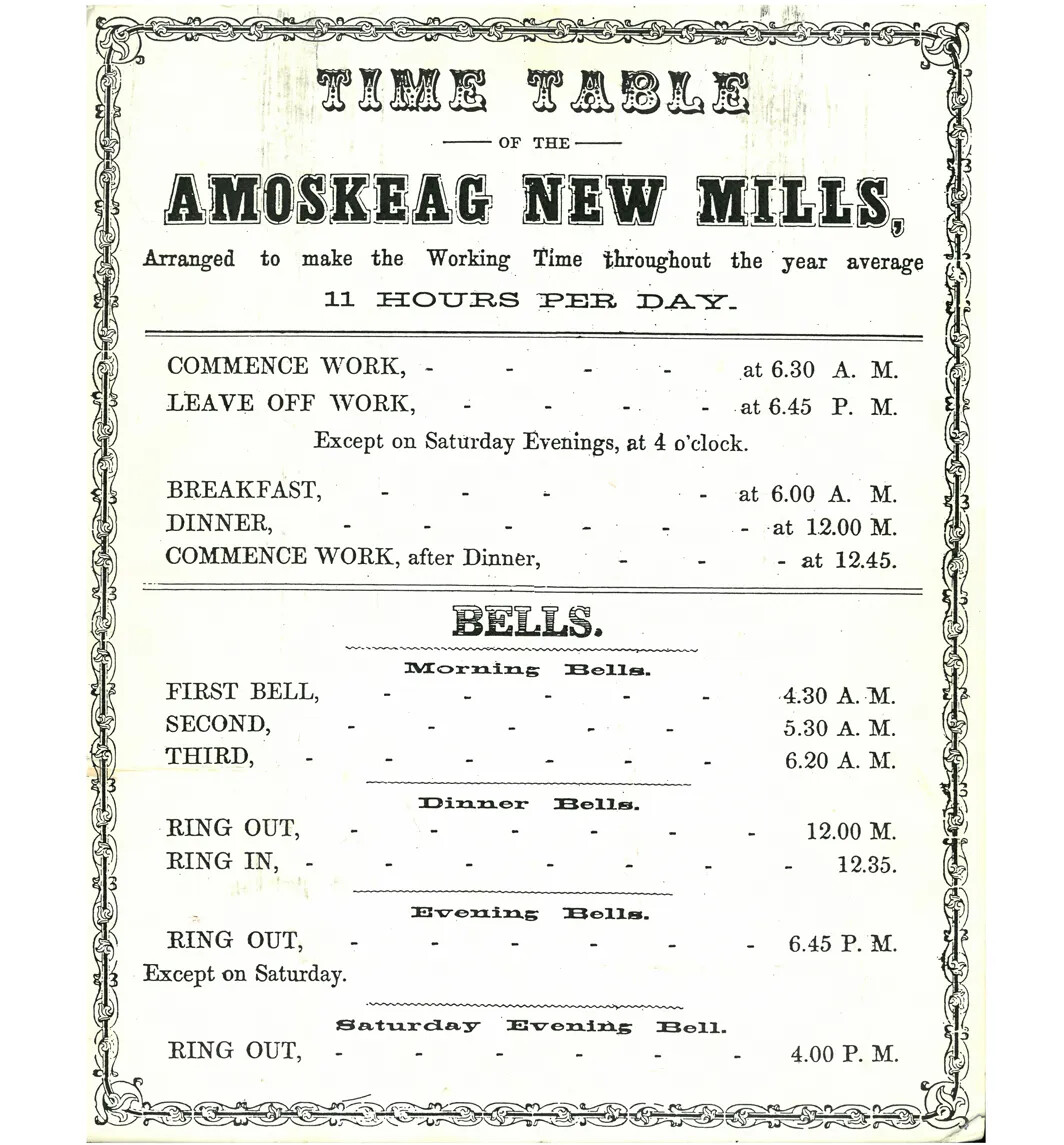

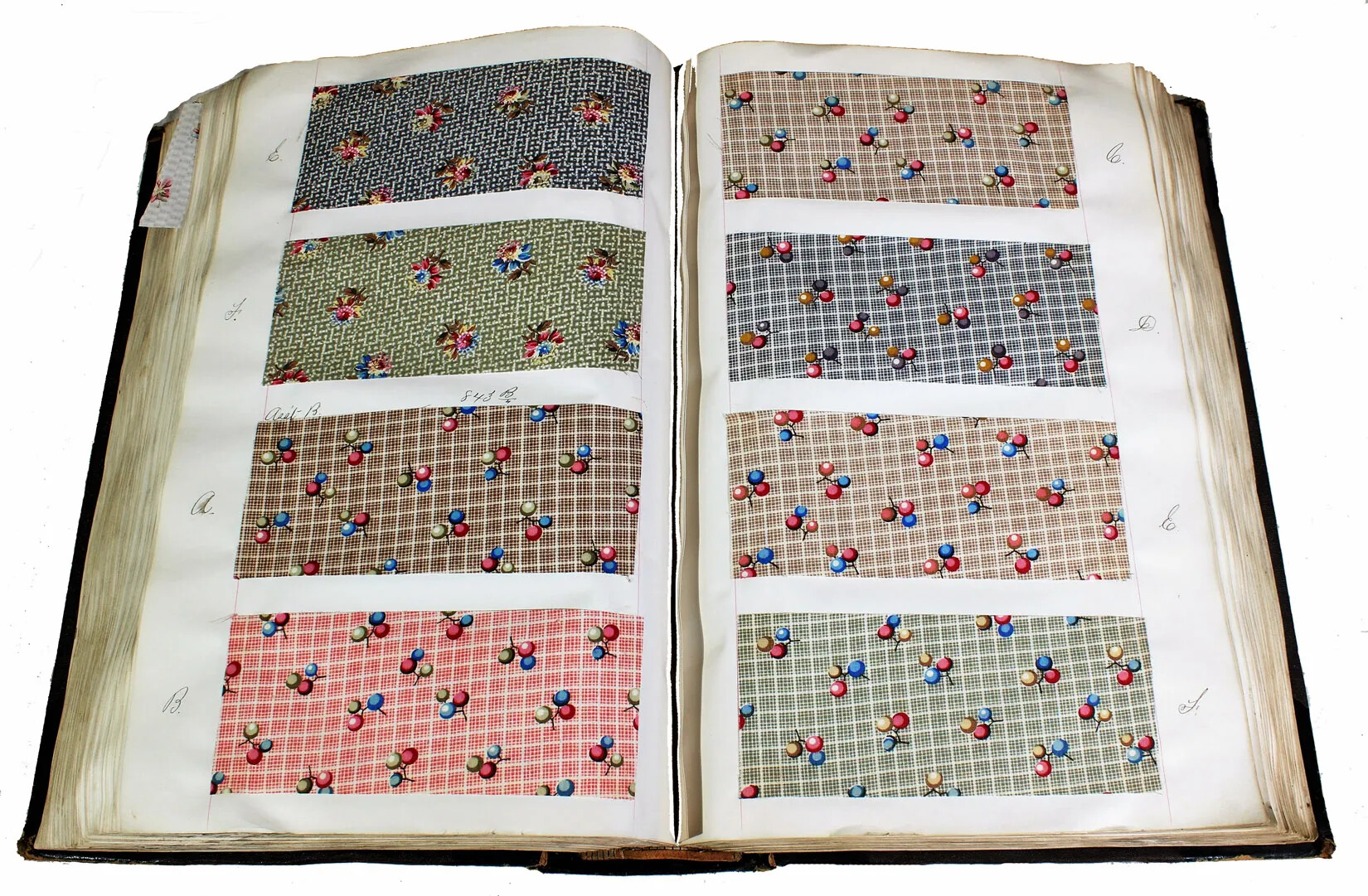

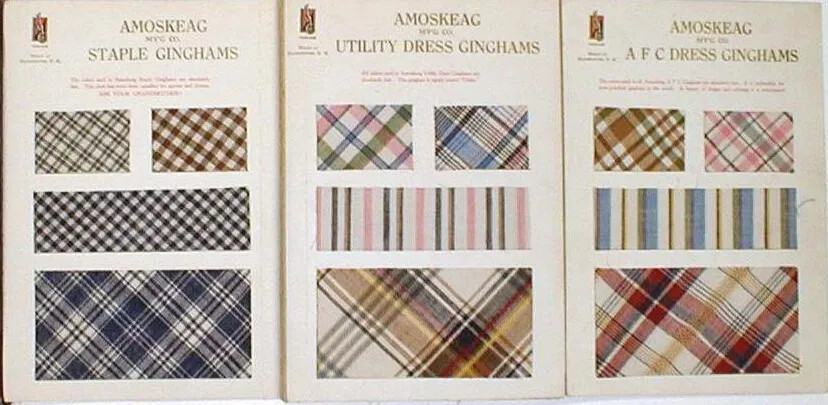

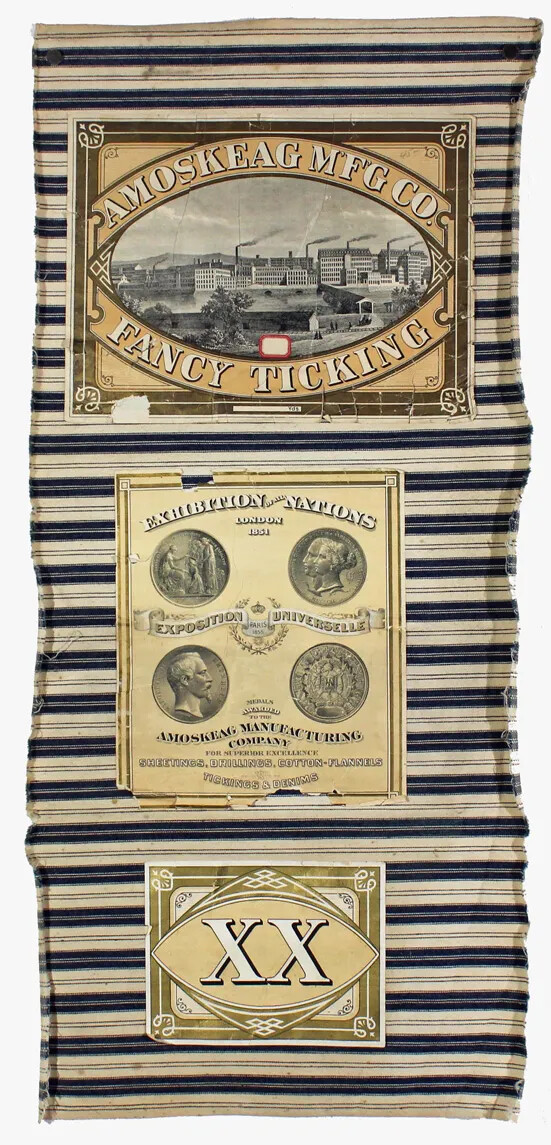

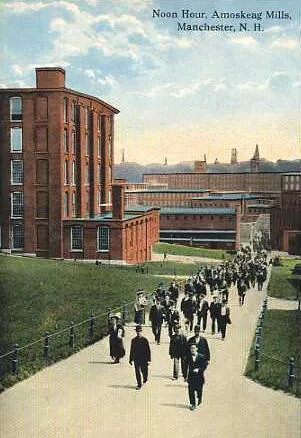

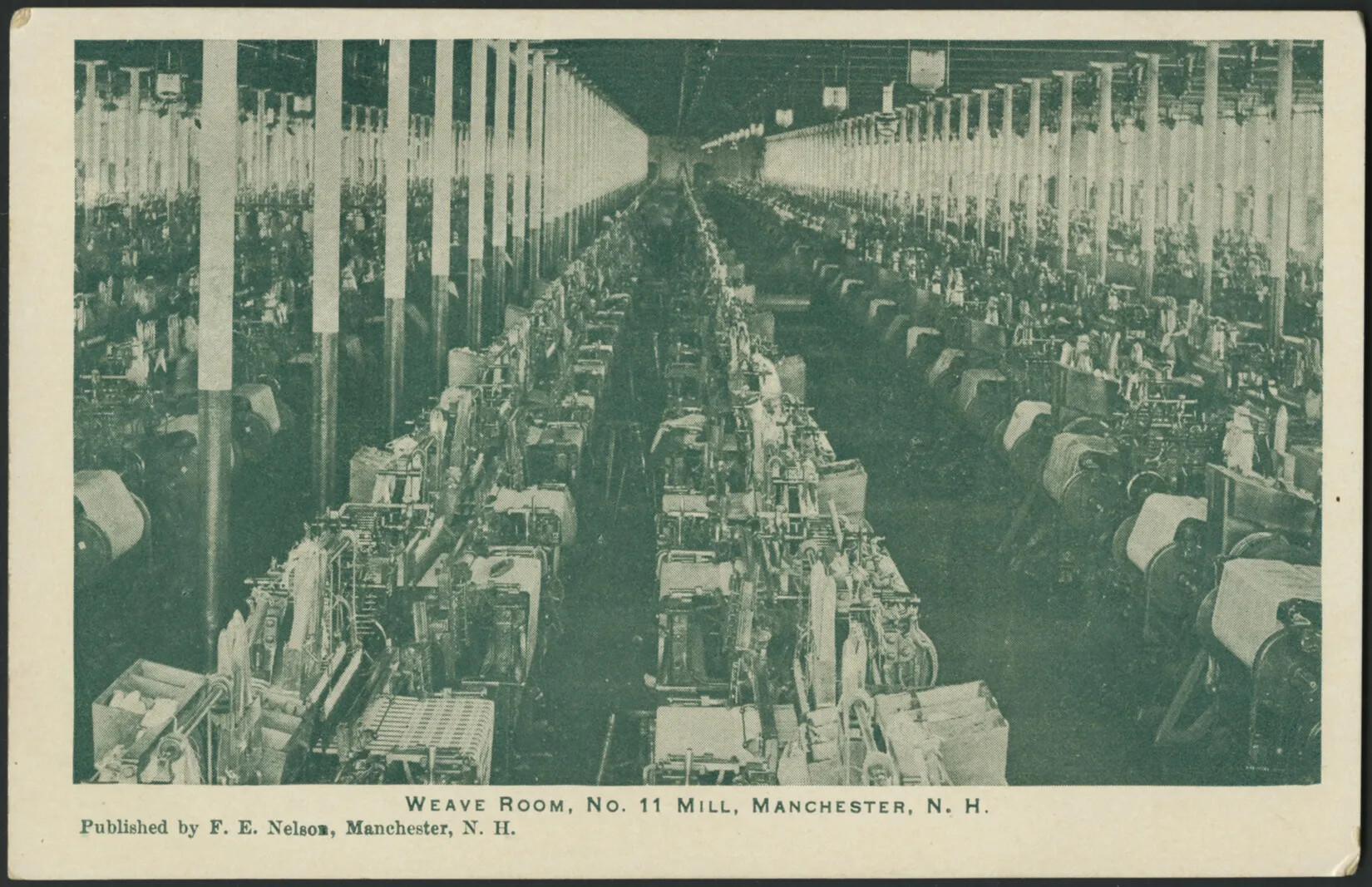

At its height in the 1910s, Amoskeag employed more than 17,000 people. By the end of a six-day work week, these mill workers could produce a total of 5 million yards of cloth, with 470 miles of cloth being finished each day. Amoskeag quickly became the largest producer of cotton cloth in the world, and, in 1873, it became the main supplier of denim used to make Levi jeans. The company was especially famous for its dress goods, particularly its gingham, which was a popular fashion trend at the time.

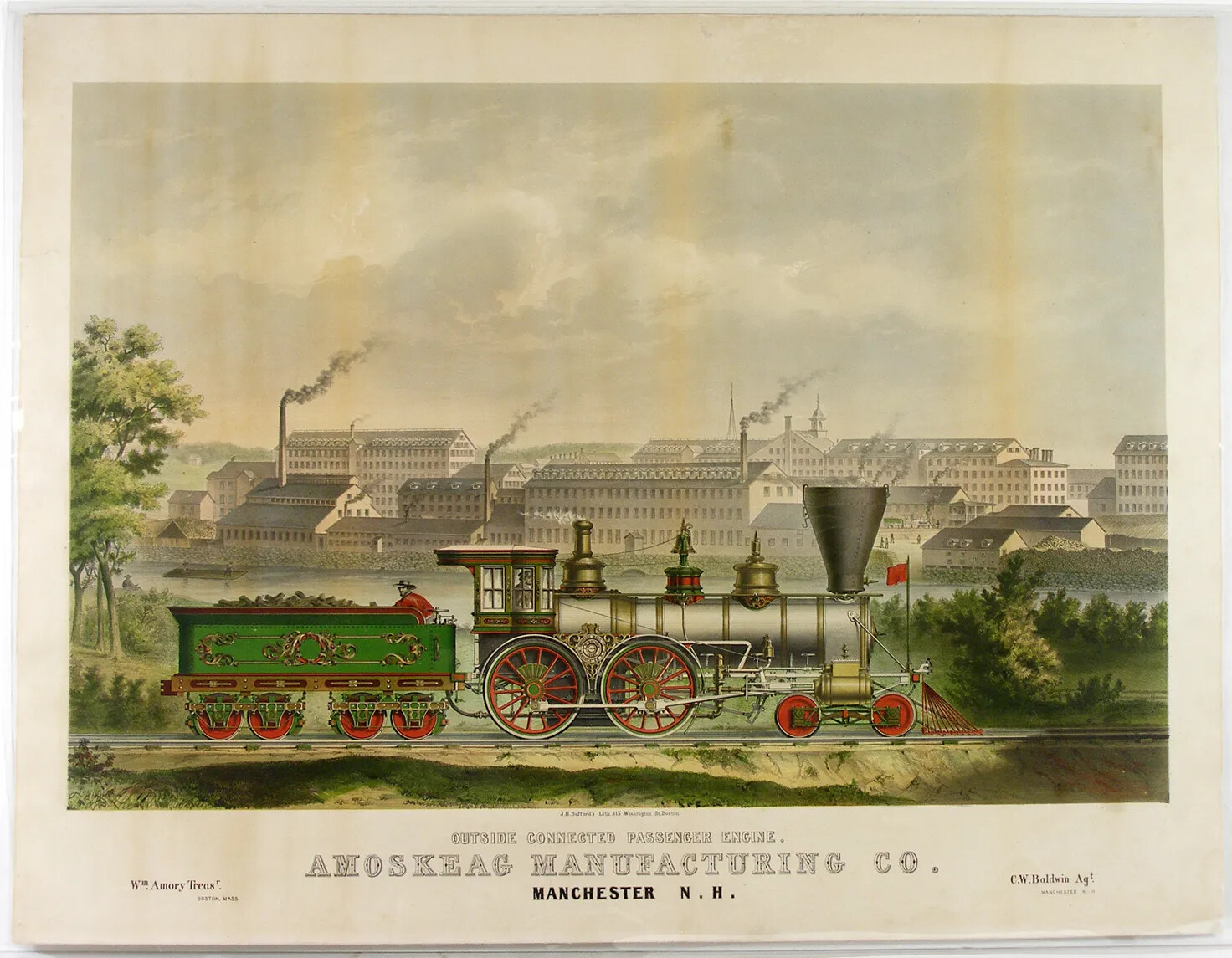

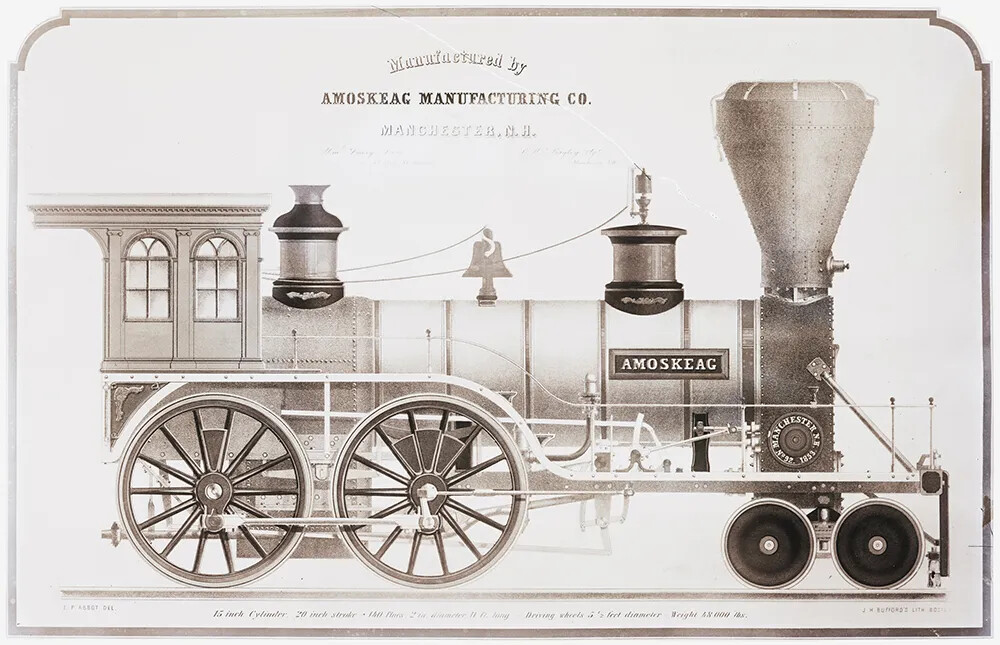

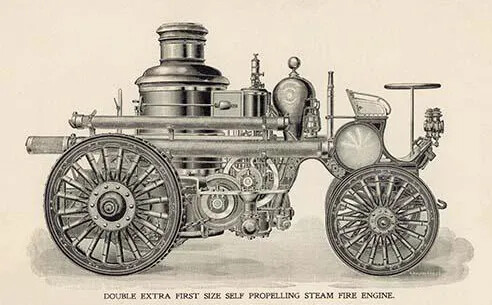

Much of Amoskeag’s success relied on the railroad, which allowed the company to expand its sales beyond the Northeast. Yet the company did not always limit itself to textile production. During the Civil War in the 1860s, when cotton from the South became scarce, the company directed its efforts to the production of carbines, Springfield muskets, sewing machines, locomotives, and fire engines. By the end of the 19th century, Manchester had become a center for New Hampshire’s flourishing shoe industry.

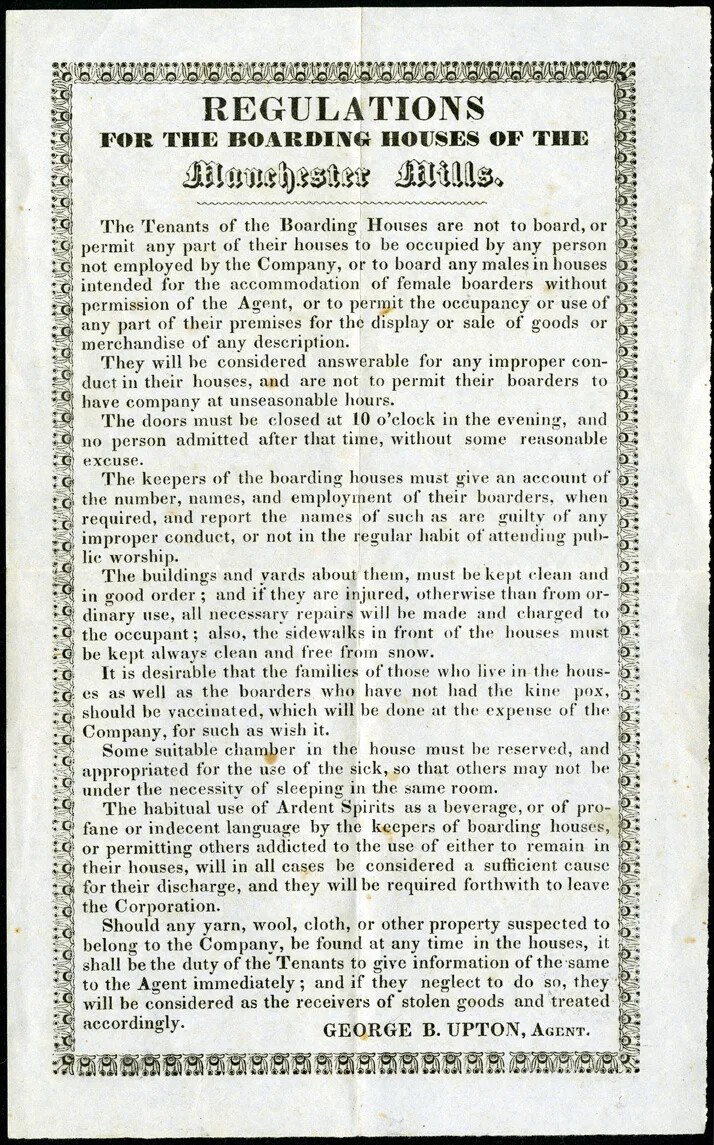

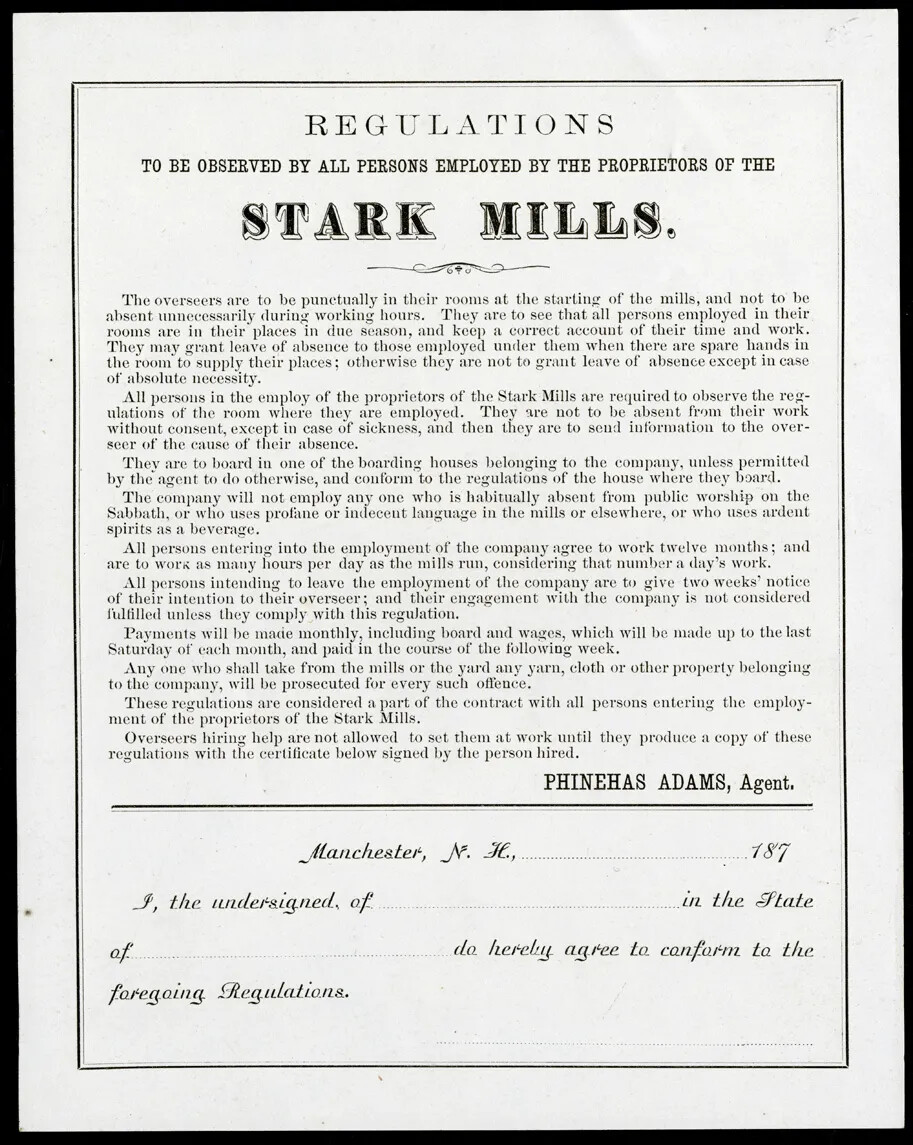

The city of Manchester expanded alongside the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company, with much of the city’s development controlled by the company. Amoskeag planned out the city’s center along Elm Street, set aside land for public parks, and organized housing for its employees.

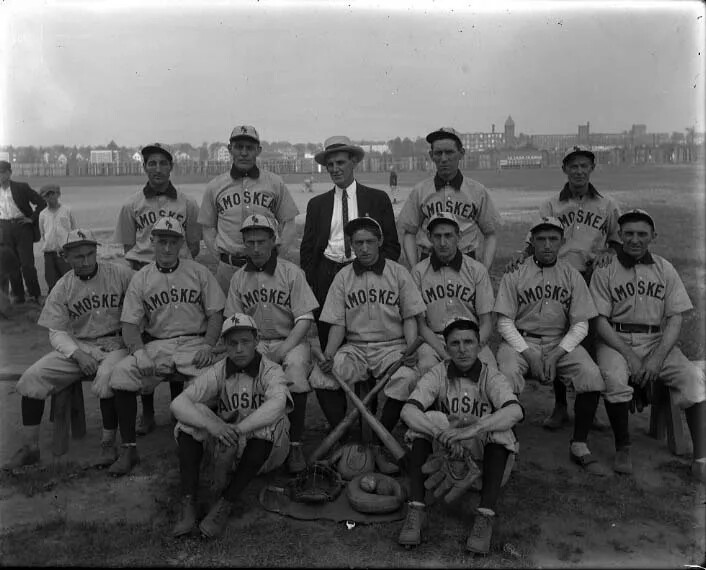

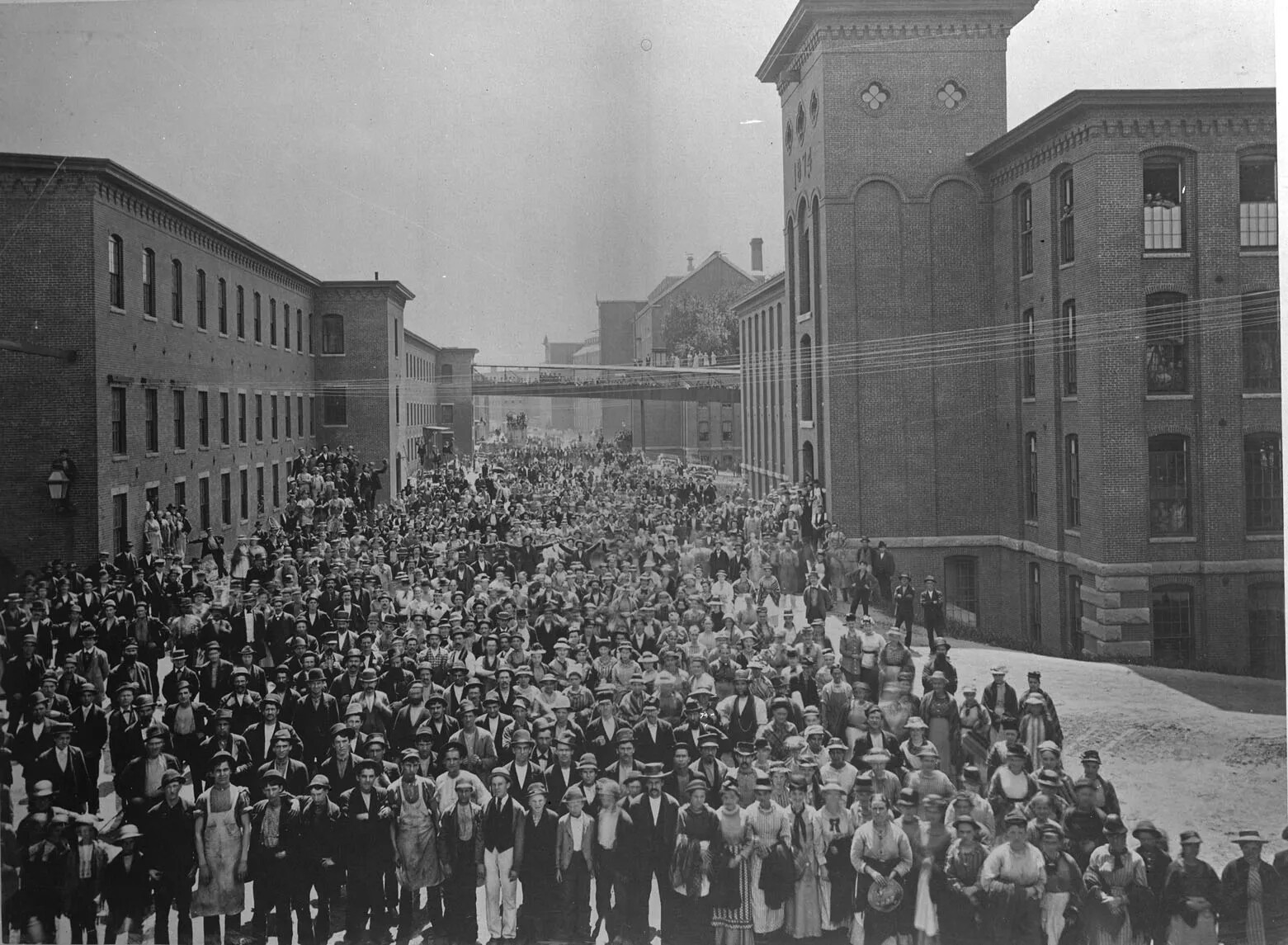

Many of the factories’ first employees were young women, who came to the city from nearby farming communities. But as the need for labor increased, Amoskeag soon relied on newly arriving immigrants from Quebec, as well as those from Ireland, Greece, Germany, Sweden, and Poland. As each immigrant group moved into the city, neighborhoods based on ethnicity soon dominated the character and culture of the City of Manchester.

Amoskeag also came to rely on children as a labor source. Because children were smaller than adults, they could climb up into the machines if something broke. Their small fingers also made them well suited to the delicate work of making textiles. But these tasks were not without incident, as injuries, illnesses, and fatalities from accidents were common. The poor working conditions of child laborers inspired the progressive photographer, Lewis Hine, to visit Manchester in 1909. His photographs of children in the mills proved influential in turning public opinion against child labor and resulted in the passage of several child labor laws at the turn of the 20th century.

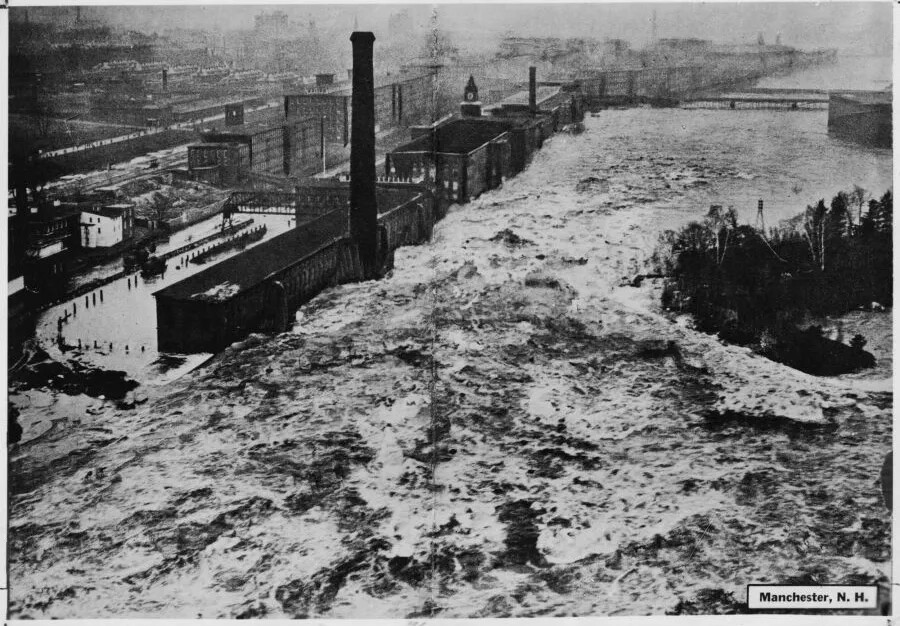

Once the dominating industry in Manchester, the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company began to lose its grip on both its workers and its stance in the textile world in the 1920s. Though Manchester was long considered the “strike-less city,” the loyalty felt by Amoskeag workers towards the company began to recede after Amoskeag announced a 20 percent cut in pay and an increase in the work week from 48 hours to 54 hours in February 1922. The resulting “Strike of 1922,” lasting nine months, cost the company and its employees millions of dollars in production and wages. Aging machinery and the Great Depression of the 1930s provided the final blows. On December 24, 1935, the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company closed its doors and filed for bankruptcy. Damage inflicted upon the mill buildings by a massive flood in the spring of 1936 further solidified the closure of the millyard.

The National Park Service once approached the City of Manchester about turning the former mill buildings into a park that would commemorate the nation’s industrial heritage. The city turned them down, and the national park instead went to Lowell, Massachusetts. Today, the former millyard has been revitalized, and the renovated mill buildings serve a variety of purposes, including office spaces, restaurants, college classrooms, apartments, and art studios.

This primary source set guide can be used in several ways to explore the story and significance of the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company. It is not necessary to use all sources in a set to create a meaningful inquiry. Rather, educators are encouraged to select—or have their students select—the sources best suited to your project.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

- Creamer, Daniel, and Charles Coulter, Labor and the Shutdown of the Amoskeag Textile Mills (Philadelphia: Works Progress Administration, National Research Project. 1939).

- Eaton, Aurora, and Robert B. Perrault, Amoskeag Manufacturing Company: A History of Enterprise on the Merrimack River (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2015).

- Freedman, Russell, Kids at Work: Lewis Hine and the Crusade Against Child Labor (New York: Clarion Books, 1994).

- Hareven, Tamara, Amoskeag: Life and Work in an American Factory-City (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1978).

- Macieski, Robert, Picturing Class: Lewis W. Hine Photographs Child Labor in New England (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015).

- Samson, Gary, A World Within a World: Manchester: the Mills, and the Immigrant Experience (Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Press, 2000).

Focus Questions

In addition to our general suggestions for using primary source sets, consider giving students one of the following prompts for an inquiry using this primary source set about the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company.

-

1What words would you use to describe the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company?

-

2What effects do you think the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company had on the city of Manchester?