Primary Source Set - White Mountain Art

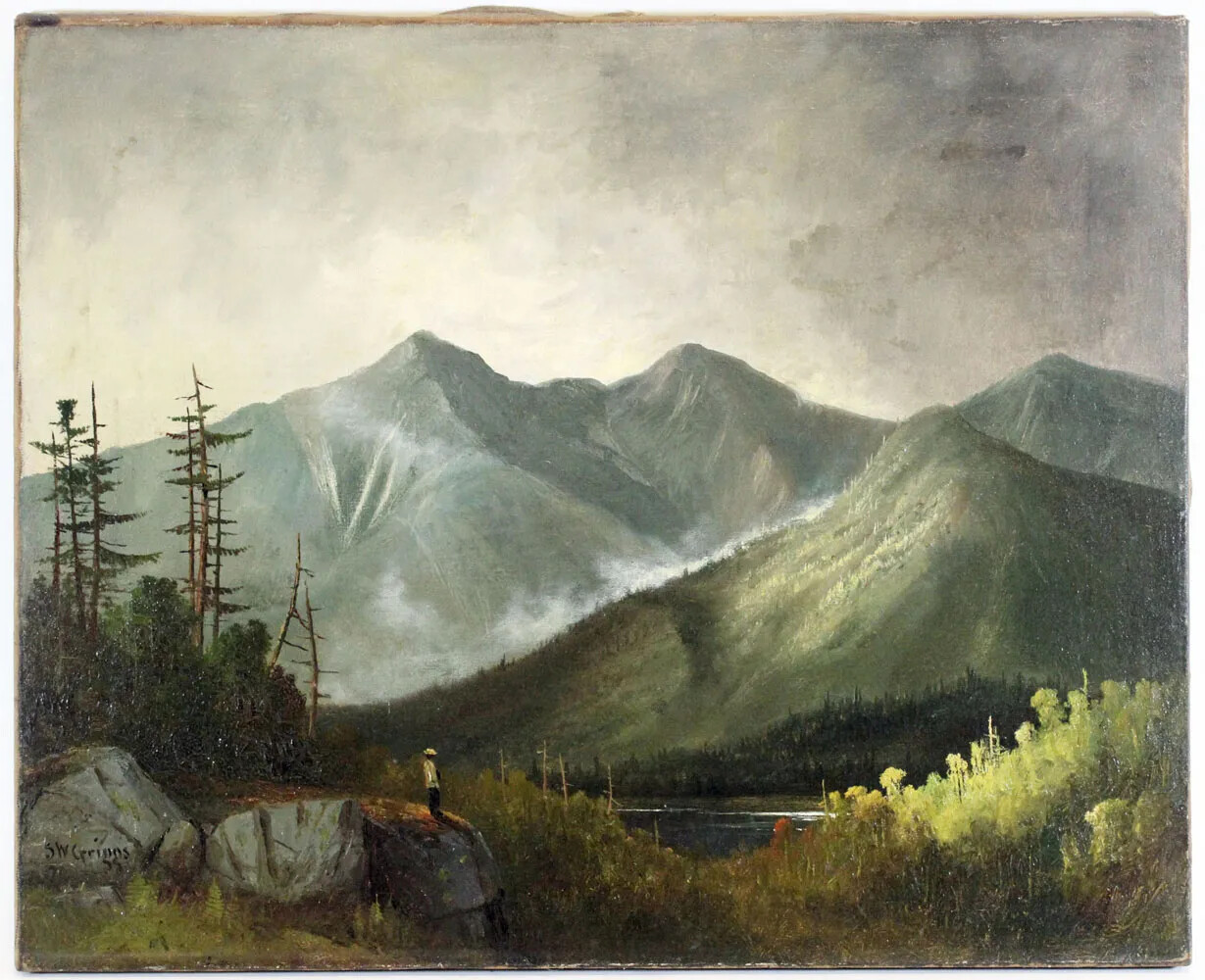

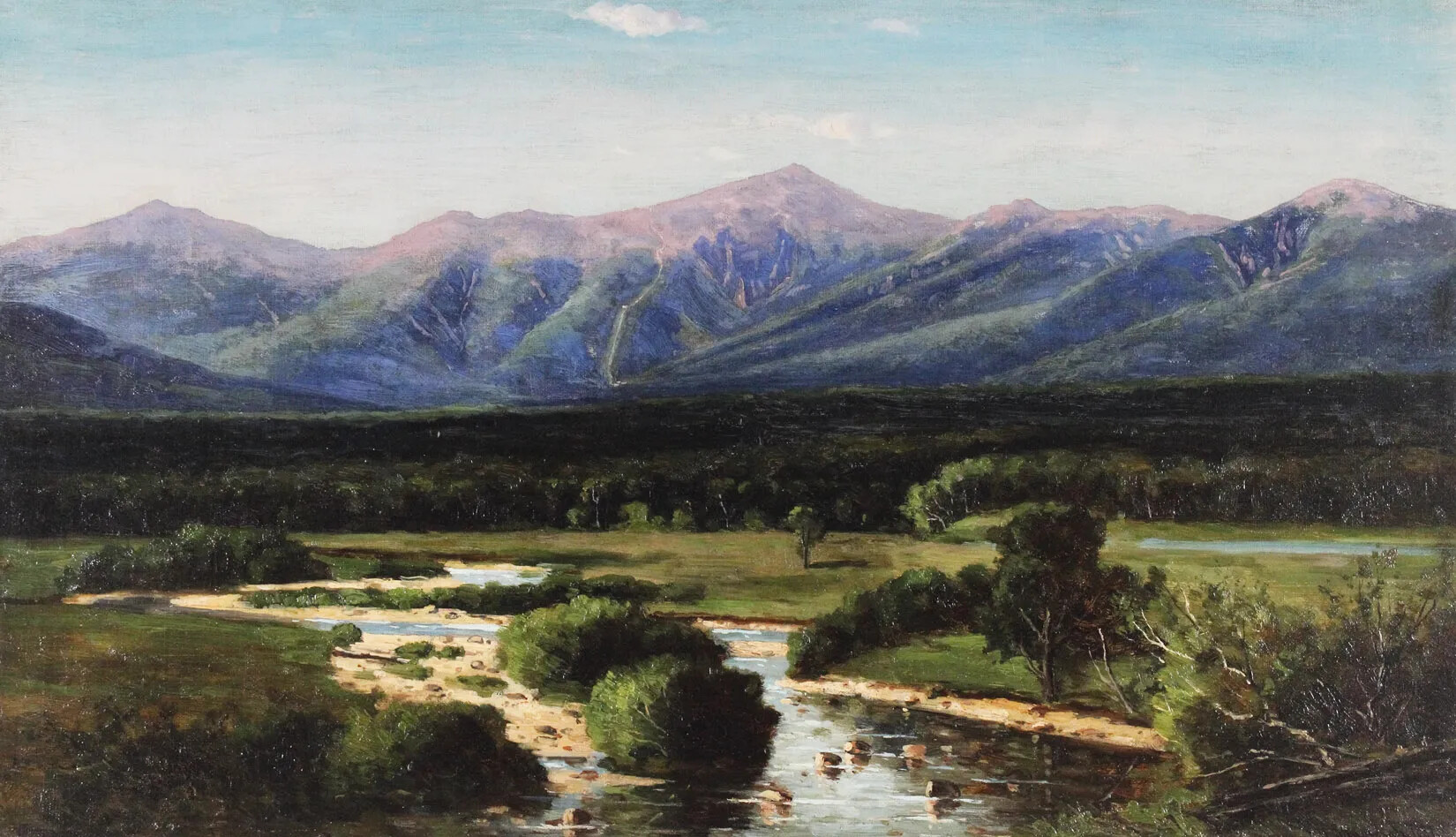

Among the tourists flocking to the White Mountains in the mid-1800s were many artists, whose sweeping landscape paintings, known as White Mountain art, helped define the region as a major tourist destination.

Background

Like many of New Hampshire’s early tourists, artists were initially attracted to the White Mountains in the aftermath of the 1826 tragedy of the Willey family, when Samuel and Polly Willey, their five children, and two hired hands were killed while fleeing a mudslide that rushed toward their home. Coupled with the events of the tragedy, romanticized stories and works of art created by writers and artists in the wake of the disaster heightened the allure of the White Mountain region. For the remainder of the 19th century, as the tourist industry in New Hampshire grew, so too did the desire for White Mountain art. In total, an estimated 450 artists created works in the White Mountain style.

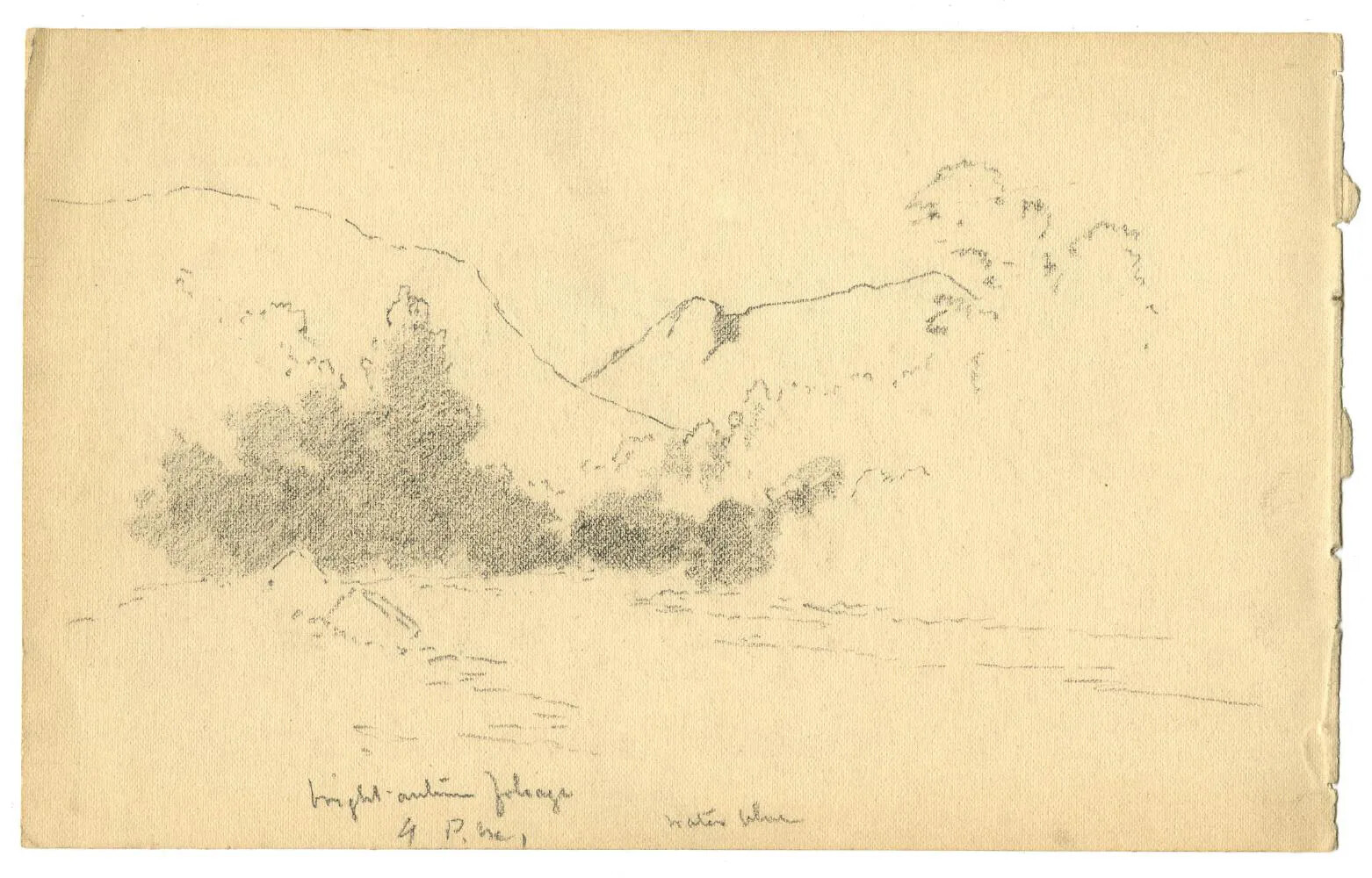

The White Mountain school art, which is a specific style rather than an actual school, focuses on large, sweeping landscape paintings that emphasize the power and glory of nature against the contrast of the insignificance of man. White Mountain art also tended to emphasize solitude and a pastoral sense of harmony and tranquility. The White Mountains’ rugged natural beauty and sparsely settled landscape served as the perfect subject and backdrop for artists seeking to capture this Romantic ideal on canvas. Although artists painted scenes of New Hampshire in all seasons, depicting the vibrant colors of a New Hampshire autumn was a particularly popular theme. The White Mountain style of art was similar to the Hudson River School, which flourished at roughly the same time in upstate New York. In fact, many artists painted in both regions. These two schools of painting sought to create a uniquely American style of art, one that could challenge notions about the superiority of the European masters. Europe had its grand cities, its cathedrals, and its ancient ruins—America had the grandeur of an untouched and unspoiled natural world.

Ironically, White Mountain art owed much of its popularity to the Industrial Revolution. In stark contrast to the rapid industrialization of cities, the raw wilderness of the White Mountains depicted in these works of art provided a new awareness of the American landscape. Prospective tourists to New Hampshire saw in these paintings a means of escape from the sweltering months of summer and the congestion of city life. Improvements to transportation and the expansion of the railroad into the White Mountains then allowed tourists to visit the very scenes they viewed in the landscape paintings.

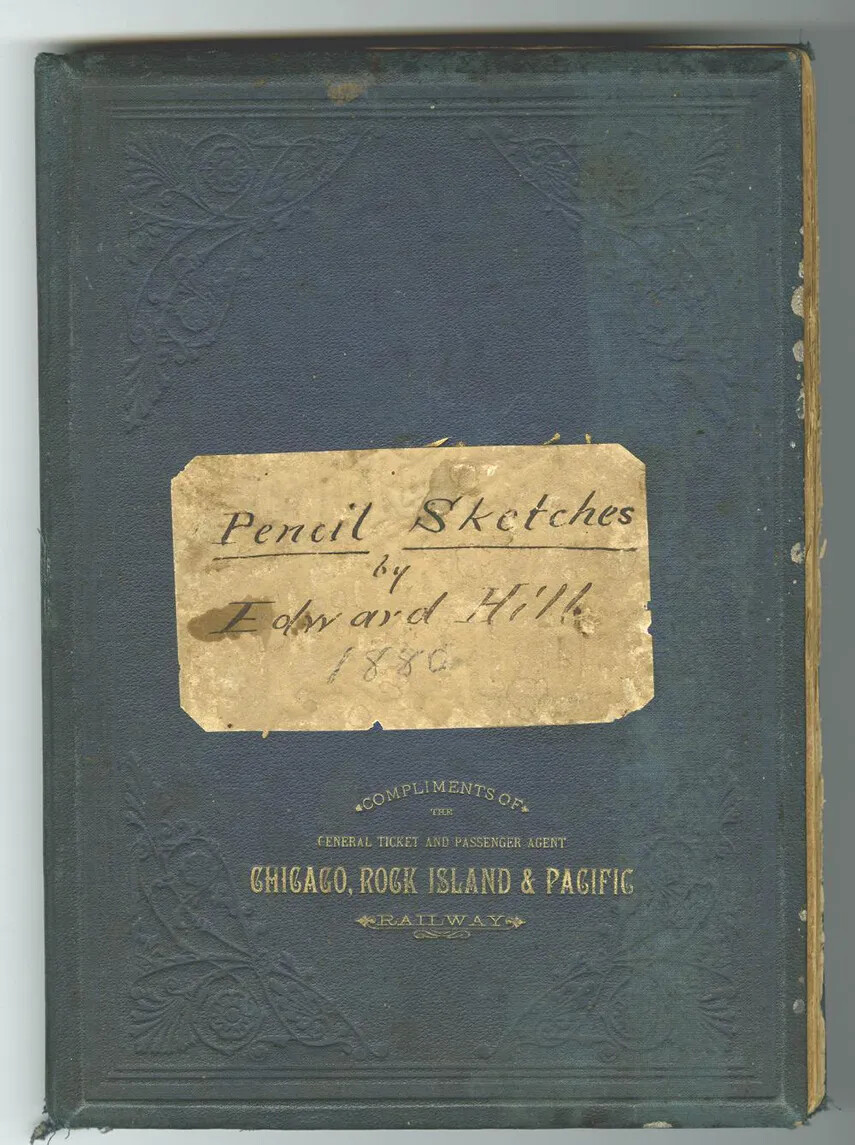

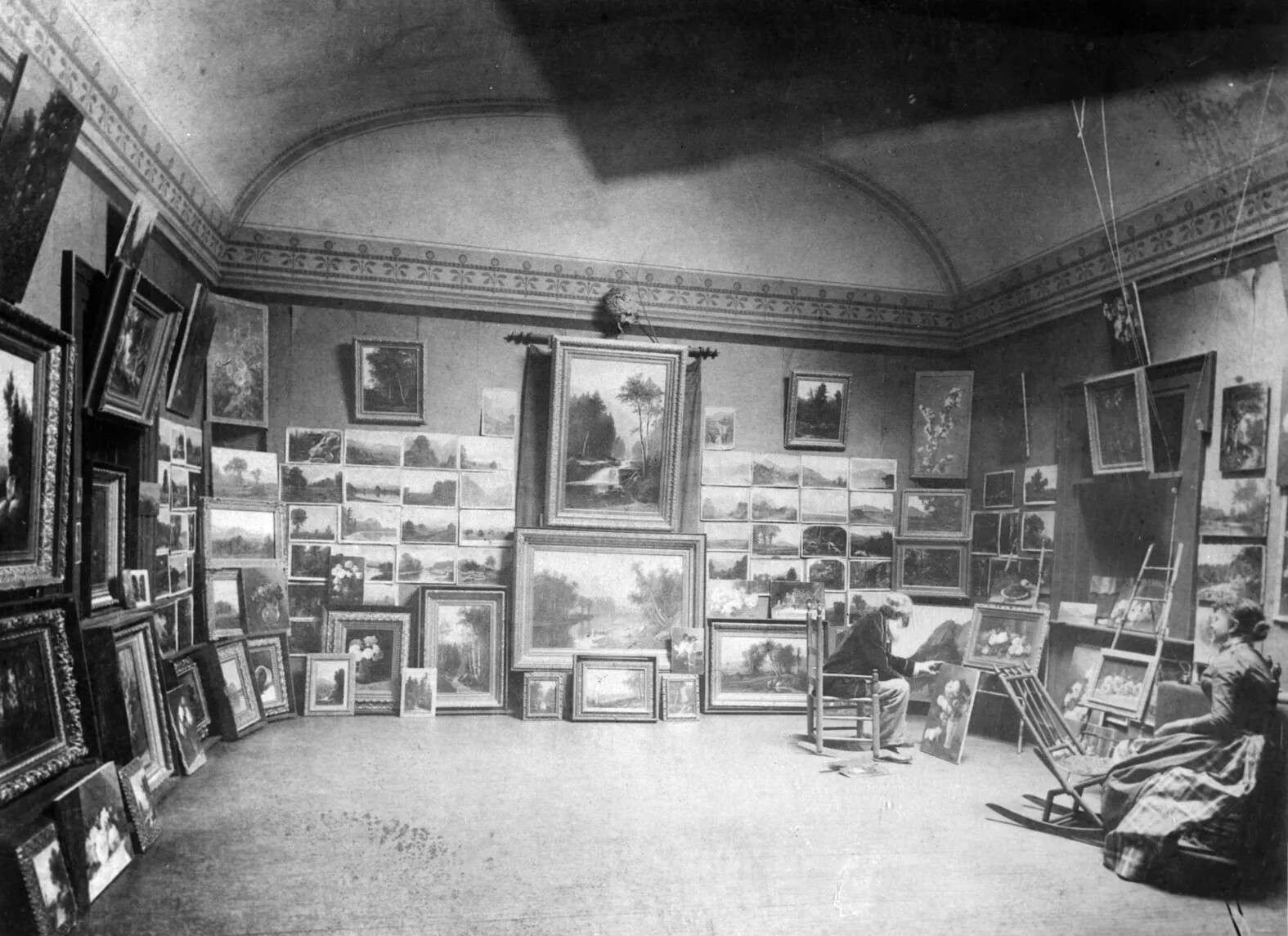

In the early years of White Mountain tourism, artists traveled to the mountains in the summer and fall to observe and sketch the landscape. They then returned to their city studios for the winter and spring months to paint the sketched scenes. Some artists, like Benjamin Champney, set up studios in the towns surrounding the White Mountains for the summer season and welcomed visitors to view and purchase finished works of art. This seasonal pilgrimage of well-known artists also attracted amateur artists to the White Mountain region. They quickly established artist colonies, communities where visiting artists could live and work among fellow painters.

Whether artists were based year-round in the White Mountains or returned to their big city studios, the works they created did much to popularize New Hampshire as a scenic and tourist destination. Many pieces were exhibited at prestigious art shows, well-known private galleries in major metropolitan areas, or national competitions. After these works were displayed, wealthy patrons purchased the art and either placed the pieces in their homes or donated them to museums.

Grand resort hotels also contributed to the growing artist communities in the White Mountains by creating the artist-in-residence position and building art studios on hotel grounds. Artists often established a summer residence at the same hotel every year. Frank H. Shapleigh was an artist-in-residence for 17 years at the Crawford House, while Edward Hill established a residency at both the Profile House and the Glenn House. Jean-Paul Selinger and his wife, Emily, had summer studios at the Glenn House, as well as the Crawford House.

Artists-in-residence were celebrities in their own right and added to the social scene at grand resort hotels. They also provided a number of services to the hotel, such as instructing art classes for guests, designing souvenir ceramics for the hotel, and decorating dinner menus. Souvenirs produced by the artists-in-residence in turn provided publicity for the grand resort hotels, attracting new and returning visitors each year.

Although the popularity of White Mountain art decreased at the approach of the 20th century, amateur and professional artists alike continue to visit the White Mountains each year, hoping to capture the majesty of the landscape in their own artistic styles.

This primary source set guide can be used in several ways to explore the significance of White Mountain art. It is not necessary to use all sources in a set to create a meaningful inquiry. Rather, educators are encouraged to select—or have their students select—the sources best suited to your project.

Additional Resources

- Consuming Views: Art and Tourism in the White Mountains, 1850–1900, exhibition, on-line exhibition, and catalog at the New Hampshire Historical Society (2006).

- King, Thomas Starr, The White Hills: Their Legends, Landscape, and Poetry (Boston: Isaac N. Andrews, 1859).

- McGrath, Robert, Gods in Granite: The Art of the White Mountains of New Hampshire (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2001).

- Timeline of New Hampshire History, New Hampshire Historical Society, nhhistory.org/Timeline.

- Wallace, R. Stuart, “The Summer Ritual of Leisure and Recreation: White Mountain Tourism at the Turn of the Century,” Historical New Hampshire 50 (Spring–Summer 1995): 109–124.

Focus Questions

In addition to our general suggestions for using primary source sets, consider giving students one of the following prompts for an inquiry using this primary source set about White Mountain Art.

-

1What words would you use to describe the scenes in the White Mountain paintings? Talk about the paintings as if you were describing them to someone who couldn’t see them.

-

2White Mountain artists also used their paintings to advertise the White Mountain region to tourists. What are the paintings showing that would make you want to visit the White Mountains?