Settling New Hampshire, 1600–1720

The 17th century was a period of great change for New Hampshire. English settlers arrived and created communities that relied on gathering the natural resources around them and shipping them back to Europe. Life for the Abenaki changed a great deal once the English arrived, as the Abenaki were pushed off their land by the English. Sometimes the Abenaki and the English worked together, and sometimes they fought one another as these two cultures met and clashed. By the early 18th century, many of the Abenaki had left this area, and New Hampshire had become a colony of Great Britain, with four big settlements for the English migrants.

As you learn more about the settling of New Hampshire, think about the following questions:

- How were the Abenaki impacted by the arrival of the Europeans?

- What did the explorers find when they first encountered the land?

- Why did the English settle New Hampshire?

- What was life like in the early English settlements?

- EXPLORERS

- NEW HAMPSHIRE'S EARLY INDUSTRIES

- ABENAKI RESPONSE

- THE FIRST FOUR TOWNS

- TOWNS BECOME A COLONY

- CONFLICT BETWEEN CULTURES

European Explorers

Why did Europeans come to the New World in the 1500s and 1600s?

Starting in the late 15th century, people from Europe became very interested in what they called the New World, which meant the Americas. Europeans had not known these two continents even existed before then. Once they discovered the New World, explorers tried to claim the land for their home countries back in Europe. Soon, most of North America, Central America, and South America were colonies of other countries in Europe.

Mason Explains: European Explorers

How did Europeans end up in America?

Who explored New Hampshire, and why did they come?

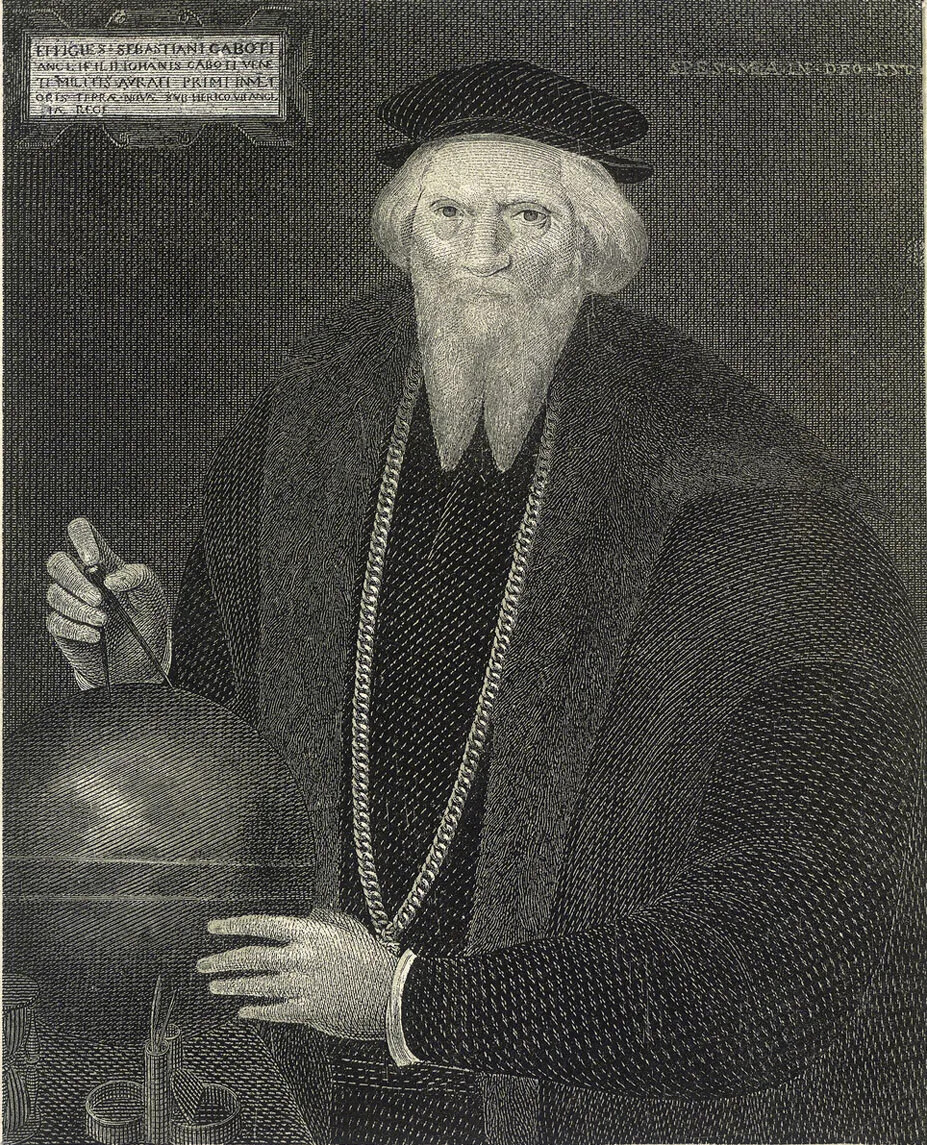

Sebastian Cabot. The first European explorer known to have visited New Hampshire was a man named Sebastian Cabot. He was Italian, but he worked for the British government. He sailed along the New England coastline in 1507 or 1508, but he did not get off his ship or actually explore the land. He later wrote that there were a lot of trees in the area that became New Hampshire.

No European explorers visited New England again for more than 100 years.

Caption:

Sebastian Cabot was the first European explorer known to have visited New Hampshire. He was Italian but worked for the English king. His father was also a famous explorer! Cabot sailed to North America around 1508. He was hoping to find a water route around North America so he could reach Asia. He explored eastern Canada and then sailed down the New England coast. He did not get off his ship or explore the land. By the time Cabot returned to England, the king had died. The new king was not as interested in exploring, so Cabot went to work as a mapmaker. Later he worked for the king of Spain and explored South America.

Caption:

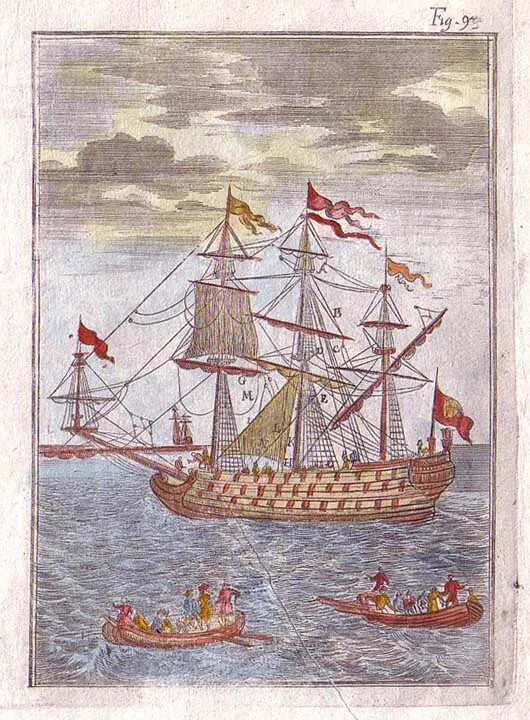

This illustration of a galleon is from a French encyclopedia. A galleon is a large, multi-decked sailing ship with three or four masts. Galleons were used from the 16th to the 18th centuries. They carried goods back and forth on trade routes, and were also warships during naval battles. Galleons were typically made of oak with pine masts.

Caption:

N'dakinna was rich in natural resources and beauty. There were lakes, rivers, streams, mountains, and trees. There were plenty of animals and plants to hunt and gather for food, shelter, and clothing.Caption:

The first English settlement in America was in Virginia in 1607. The colonists named their settlement Jamestown after the English king, James I. Life was very hard for these settlers because they had come looking for gold and did not bring enough food to eat. For the first several years, the Native Americans shared their food with the English colonists so they would not starve. Eventually, the colonists learned to plant crops and live off the land. Many more English settlers arrived in Jamestown and founded new settlements in Virginia. They were hoping to build a better life than they had in England.

Sassafras is a kind of plant that is native to North America. When European explorers started coming to North America in the late 1500s, they discovered that sassafras had two useful purposes. First, the wood from a sassafras plant was a hard wood that made good boxes. Sassafras plants also have an odor that keeps bugs and small animals, like mice, from eating the wood. So people used boxes made from sassafras to protect their things from little critters. Second, the leaves of a sassafras plant can be stewed and cooked into tea or soup and worked kind of like a medicine. Some people even said that drinking sassafras would help you live forever! Sassafras also tasted good and had a flavor that is a little like cinnamon. Sassafras products became very popular in Europe, and several expeditions came to North America in the early 1600s to collect as much sassafras as they could and take it back across the Atlantic Ocean. These expeditions were part of what Europeans called the Great Sassafras Hunt!

Martin Pring. In 1603, an expedition led by Martin Pring came to New Hampshire. He was just 23 years old at the time, but he commanded two ships and 44 men on this voyage to New England. Pring was looking for sassafras, which is a plant that people used as a medicine. He and his crew landed near what is now Portsmouth.

They explored the four rivers in that area, and they traveled a few miles inland. They didn’t find any sassafras in New Hampshire, so they left and sailed south to Cape Cod where they found lots of sassafras that they took home to England.

Just a few years after Martin Pring visited New England, a group of people founded the first English settlement in North America, far to the south in what is now known as Jamestown, Virginia.

Caption:

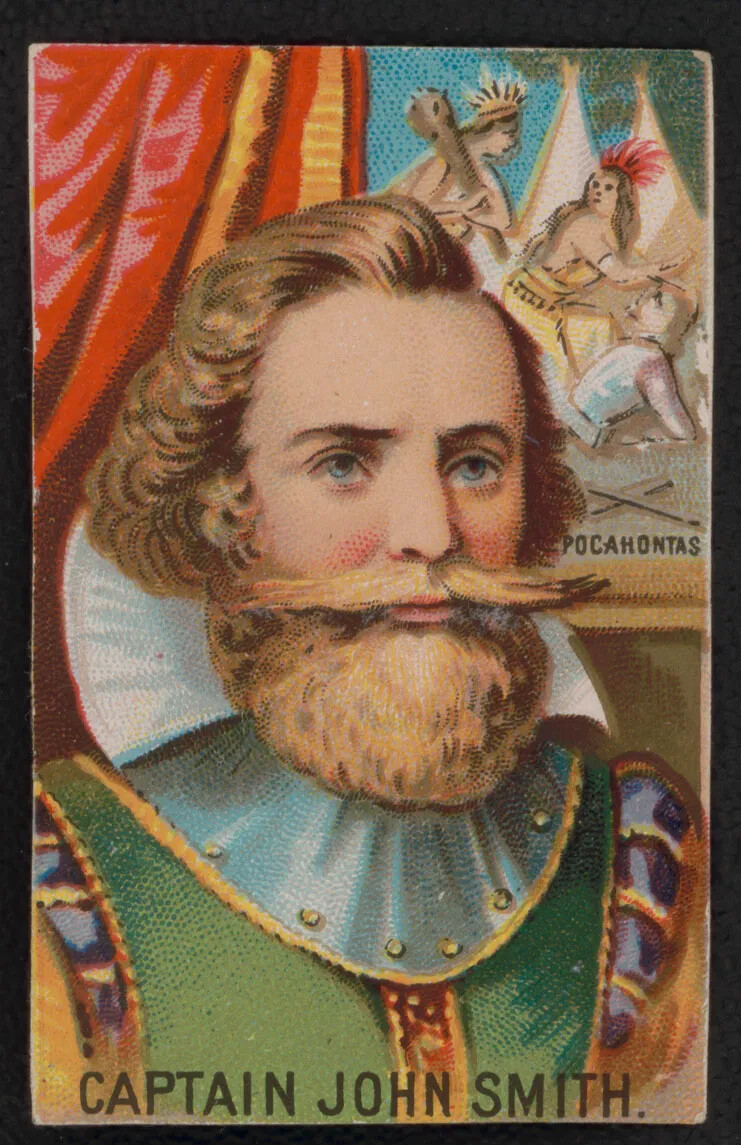

Martin Pring was the first English explorer to sail up the Piscataqua River in New Hampshire. He was only 23 years old in 1603 when he led an expedition to New England to find sassafras. Sassafras is a plant that people used as medicine. Pring and his crew explored the coast of Maine and then landed near what is now Portsmouth. They sailed 10 or 12 miles up the Piscataqua River. He didn’t find any sassafras there, though, so he continued south to Cape Cod. He found a lot of sassafras and met with the indigenous people who lived there. He sent a whole boatload of sassafras back to England, along with information about all of the plants and animals that he saw in New England. His reports helped convince English businessmen that they could make money by sponsoring settlements there. Pring continued to explore North America and Asia after this successful voyage.John Smith. John Smith was already a famous explorer when he came to New England. John Smith was one of the first settlers of the Jamestown Colony in Virginia in 1607, which was the first permanent English settlement in North America. He took a voyage north from Virginia in 1614 to see what the land was like in this area.

Smith sailed all along the New England coastline from Cape Cod to Maine. He went past New Hampshire, but he didn’t stop and look around, except for the Isles of Shoals, which are the small islands that lie 10 miles off the New Hampshire coast. He even named the islands Smith’s Isles after himself! But the name didn't catch on, and the people who came to New Hampshire after him called these islands the Isles of Shoals.

Caption:

John Smith was a famous English explorer. In 1607, he helped settle Jamestown, Virginia, the first permanent English settlement in North America. In 1614, he set out to explore the land north of Virginia. He named the area “New England.” He sailed all along the coast from Maine to Massachusetts. He stopped at some islands off the coast of New Hampshire and named them “Smith’s Isles” after himself. Today we call them the Isles of Shoals. He traded with the indigenous people for beaver pelts, which he brought back to England. He also brought back a lot of codfish. When he returned to England, he drew a map of the area and published a book about what he saw there. His stories of the natural resources and good climate in New England encouraged English settlers to move there.

Caption:

John Smith was an English sea captain and explorer. In 1614, he sailed along the New Hampshire coast. He stopped at the small islands off the coast and named them after himself, Smith's Isles. They are now called the Isles of Shoals. He named the whole area New England after his home country. When he went back to England, he wrote all about the natural resources he had seen. His writings helped convince the English that it would be a good idea to settle in New Hampshire. This portrait of John Smith is from a map made in the 1630s based on a map originally drawn by Smith.Caption:

In the early 1600s, a few European explorers came to New England. Among them was Captain John Smith, who was famous for helping to found the Jamestown colony in Virginia. Smith landed on a small group of islands off the coast of New Hampshire in 1614. He originally named the largest island after himself—Smith Island—but today we know all of these islands as the Isles of Shoals. When Smith returned to England he wrote a book about what he had seen in New England and told his readers that there were more fish in New England waters than anyone could imagine. He also wrote about how beautiful the land was, how plentiful the trees and animals were, and how perfect it would be to settle there. His book encouraged many people to think about coming to New England.

Caption:

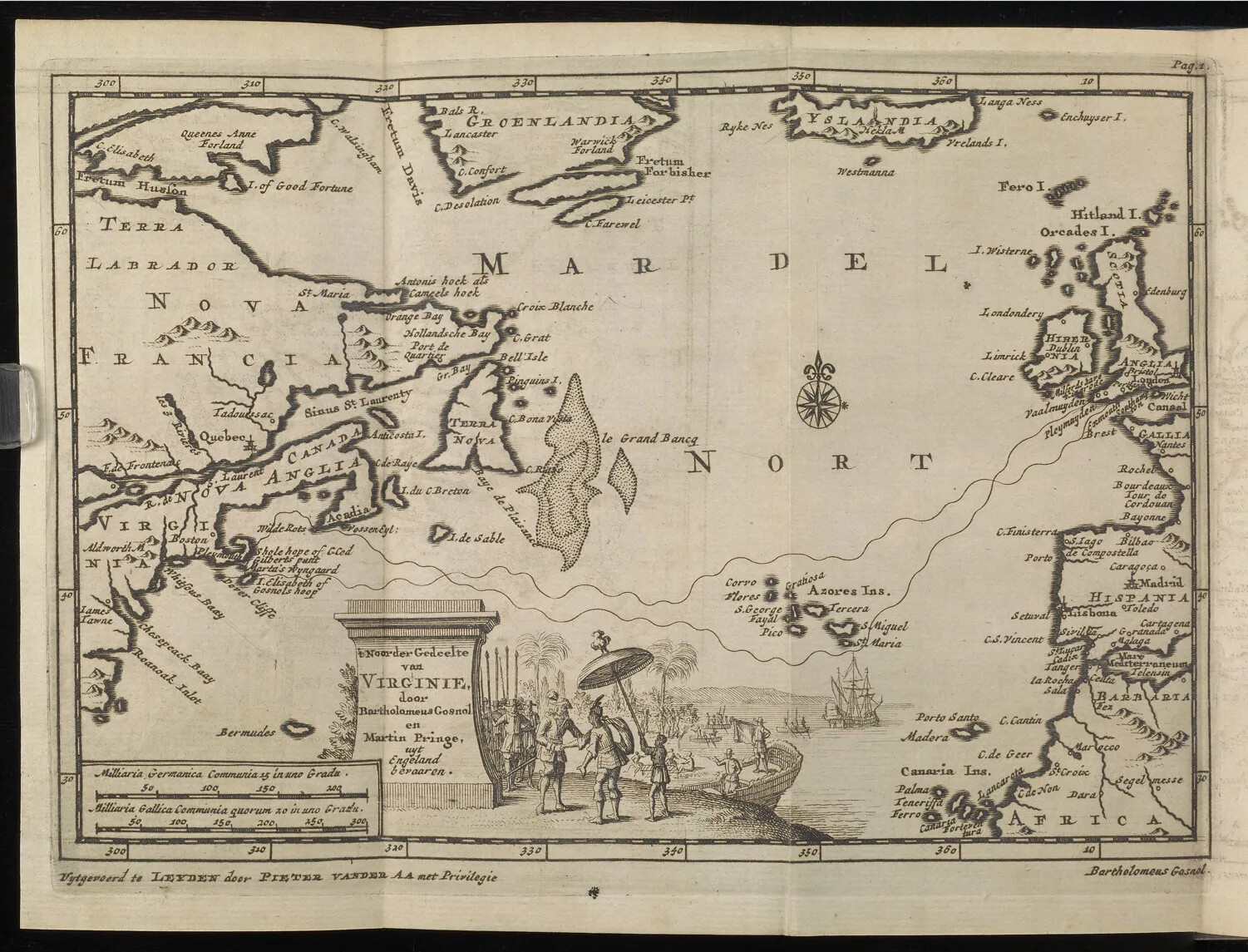

Bartholomew Gosnold was an Englishman who led the first known European exploration of New England in 1602. He explored from the coast of Maine all the way down the coast of Massachusetts, an area that was then known as "North Virginia." Several of the names he gave places are still used today. He named Martha's Vineyard, an island off the coast of Massachusetts, for his daughter, and he named Cape Cod because he saw so many codfish there. Gosnold did not stop to explore the area that eventually became New Hampshire. A few years later, Gosnold helped found Jamestown, Virginia, the first permanent English settlement in North America.What did the first explorers find?

Martin Pring and John Smith were impressed by how many natural resources they saw in New Hampshire. There were lots of trees that could be used to make lumber to build ships or houses, and many plants and animals. There were also lots and lots of fish in the ocean.

When they returned to England, Pring and Smith each wrote a book about what they had seen. They told people about all the natural resources in New England, which would allow settlers to build new lives there and maybe even get rich. Many people in England read these books and decided to come to the New World to make their fortunes.

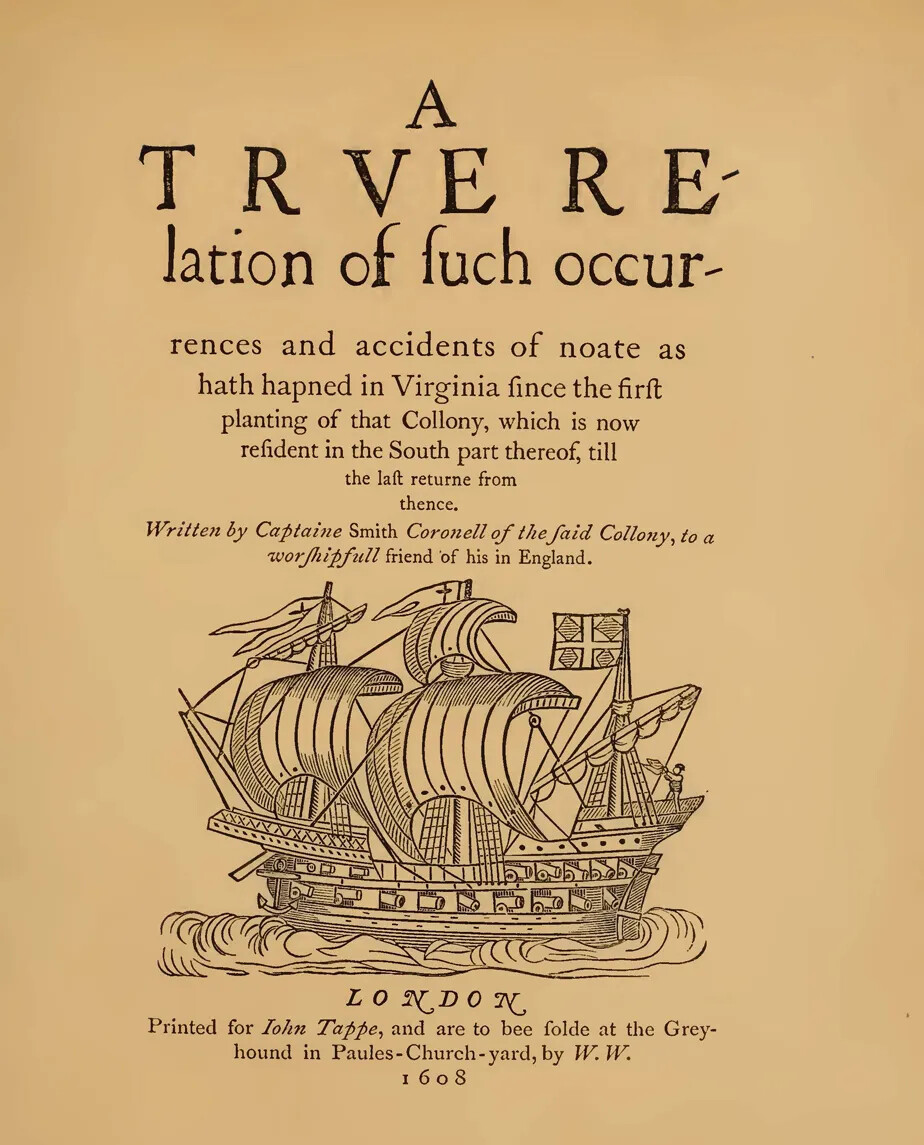

Caption:

This is the title page of a book written by Captain John Smith. Smith was an English explorer and one of the founders of the Jamestown colony in Virginia. He also traveled to New England, and even gave the region its name. Smith wrote several books to encourage English people to settle in the New World.

Caption:

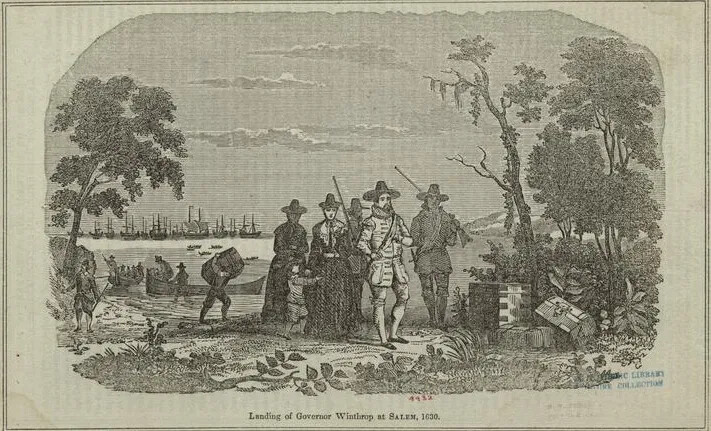

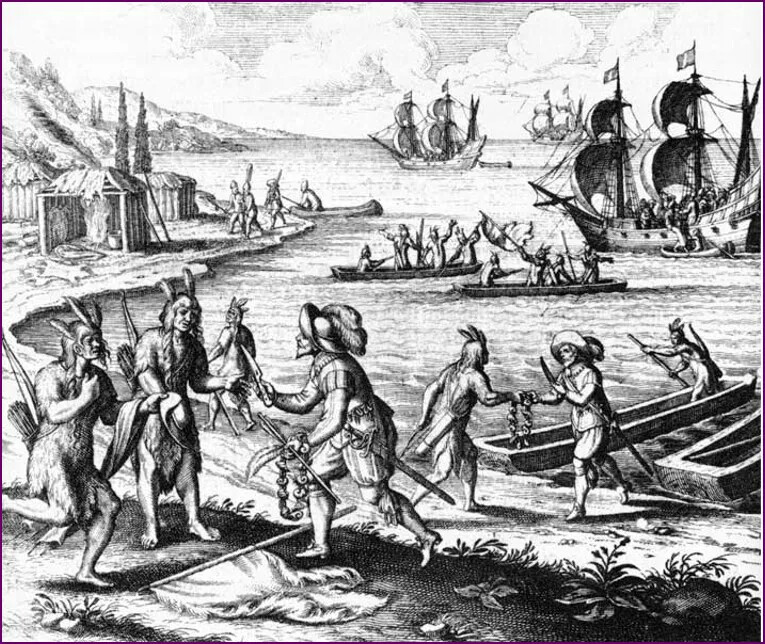

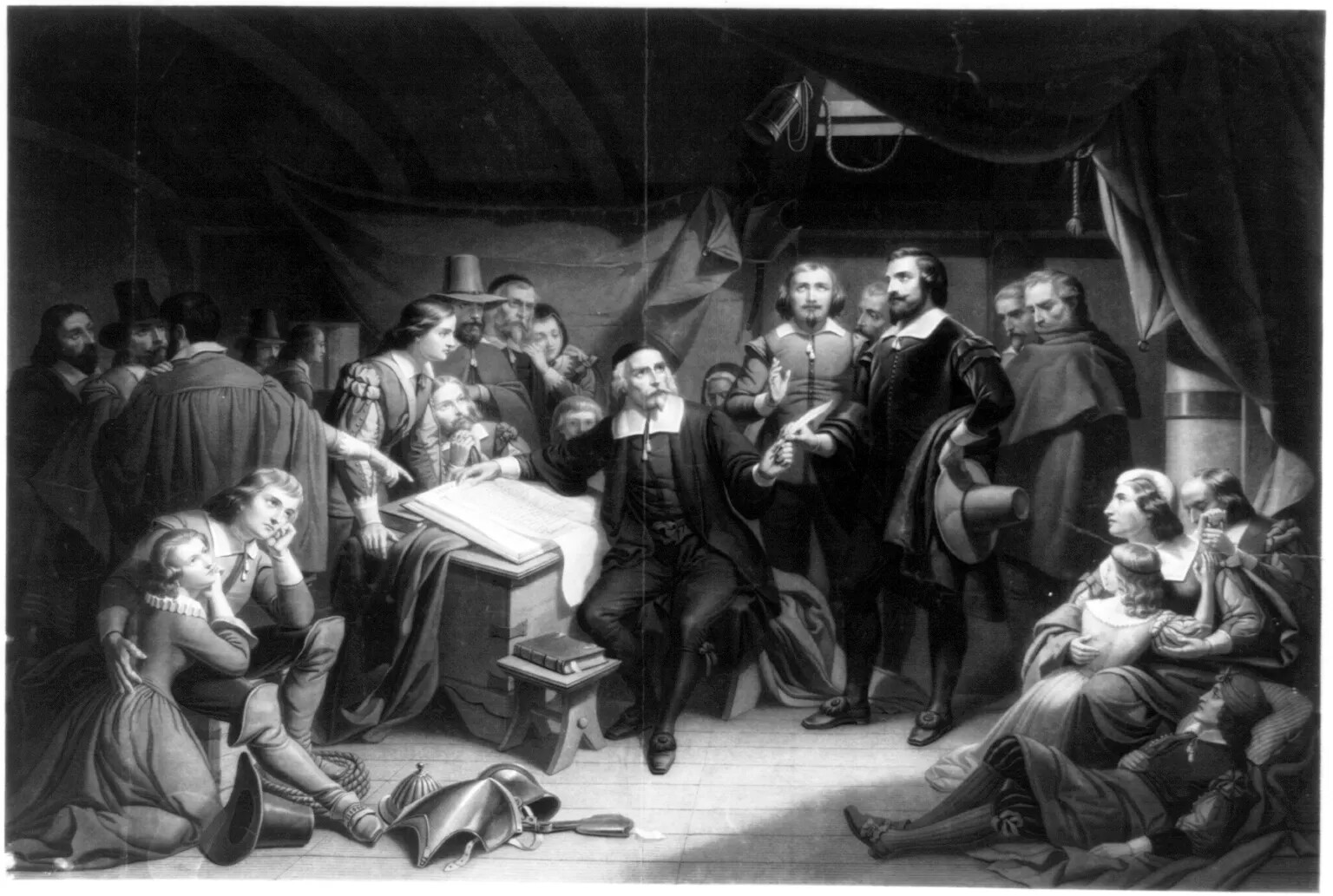

Once the English explorers went home and wrote about all of the natural resources available in New England, many people decided they wanted to move to the New World. The English government claimed New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut as colonies. This meant that these colonies were part of Great Britain. The English settlers brought English customs and traditions with them. This picture shows John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts colony, landing in New England in 1630.Caption:

A second group of English colonists, called the Pilgrims, landed in Massachusetts in 1620. The Pilgrims came to America because they wanted to practice their religion freely. They built a settlement that they named Plymouth Plantation. They also wrote the Mayflower Compact, which was a set of laws for them to live by. Life was very hard for the Pilgrims because they did not have enough food, but the Native Americans helped them learn how to survive in the New World. In the coming years, thousands of people came to Massachusetts because they wanted to live where they would be free to practice their own religion.The government in England also claimed New Hampshire as a British colony, along with Massachusetts and Connecticut. These three British colonies made New England part of Great Britain, which meant the British government claimed a right to govern this region.

English people settled in New England, and they brought with them customs and traditions from England. By claiming New England as part of the British Empire, the British government warned other European countries, like France or Holland, not to try to settle their own people there.

New Hampshire was a British colony for the next 150 years, until the American Revolution in 1776, when the American colonies declared their independence from Great Britain. This period, from the arrival of the first English explorers in 1603 until American independence in 1776, is called the colonial period of New Hampshire’s history.

Caption:

The British Red Ensign flag was flown in the 13 colonies from 1707 until American independence. The American colonies were part of Great Britain, so the British flag from that time is in the top left corner of this flag.

The country of Great Britain goes by many names, including England or just Britain. The people who live there are known as the English or the British. As each colony in America was founded by the English, the British king or queen at the time claimed it for Britain. By the 1760s, Great Britain had started establishing colonies all over the world, not just in America.

Let's Review!

What are the big ideas in this section?

The New World

In the late 15th century Europeans became interested in claiming land in the “New World,” or the Americas, for their home countries in Europe. They did not know before then that the continents existed. Soon, most of the land was claimed by Europeans for their colonies.

Early Explorers

The three earliest explorers of New Hampshire were Sebastian Cabot, Martin Pring, and John Smith. Sebastian Cabot did not land but Martin Pring explored near what is now Portsmouth looking for sassafras. John Smith did not come to the mainland but named the Isles of Shoals after himself as he passed by.

New Hampshire's Natural Resources

The early explorers brought back word to Europe and wrote books about what they found. Martin Pring and John Smith especially wrote about the plentiful natural resources in New Hampshire, like fish and forests.

New Hampshire as a Colony

The government in England claimed New Hampshire as a British colony. Soon English people settled in the area. New Hampshire was a British colony for the next 150 years until the Revolutionary War.

New Hampshire's Early Industries

Why did English settlers come to New Hampshire?

In the early 1620s, English investors organized groups of settlers to travel to New Hampshire and set up outposts here. Their goal was to make money from New Hampshire’s many natural resources.

There were three industries that New Hampshire became known for during this period, called the three F’s: fish, fur, and forests.

Caption:

A seal is a mark on a document to make it official. The first state seal shows some important symbols of New Hampshire. On the left is a codfish. On the right is a white pine tree. In the middle there are five arrows bound together. At the time this seal was created, there were five counties in New Hampshire. This was the first seal designed after New Hampshire and the rest of the original 13 colonies declared independence from England in July 1776. The words on the seal are in Latin. Sigill rei pub Neohantoni means "seal of the state of New Hampshire." Vis unita fortior means "a united force is stronger."Fish

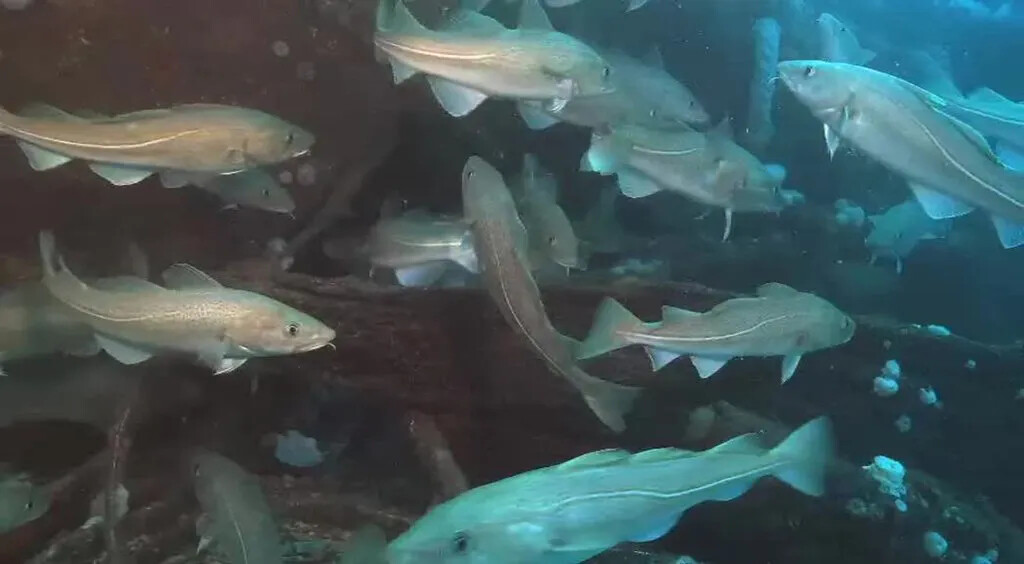

The Atlantic Ocean off the coast of New England was full of huge schools of fish in the 1600s. English explorers wrote that they thought the area could never run out of fish. Some even said that there were so many fish that a person might be able to walk across the ocean on the backs of the fish! In reality, no one could really walk on fish that were swimming in the ocean, but the imagery the explorers used helped people understand how many fish there were in the waters of New England.

There were many different kinds of fish, but the most common was cod. Cod was an inexpensive food for people in Europe, and for most Europeans it was a staple of their diet. As cod became a popular food in Europe, more and more fisherman came to New England to catch cod and ship it back to Europe.

Caption:

Atlantic cod is a type of fish found in the northern Atlantic Ocean. Fishing for cod was a very important industry in New Hampshire during the colonial period. Fishermen could catch the cod, dry and salt it to preserve it, and ship it to Europe. Cod was a very popular food in Europe. At one time there were millions of cod in the Atlantic Ocean, but now there aren't as many because it was overfished.English fishermen set up the first settlements in New Hampshire along the coast and on the Isles of Shoals. These settlements were very simple, just a collection of small shacks where the fishermen could sleep and eat when they weren’t out in boats catching fish.

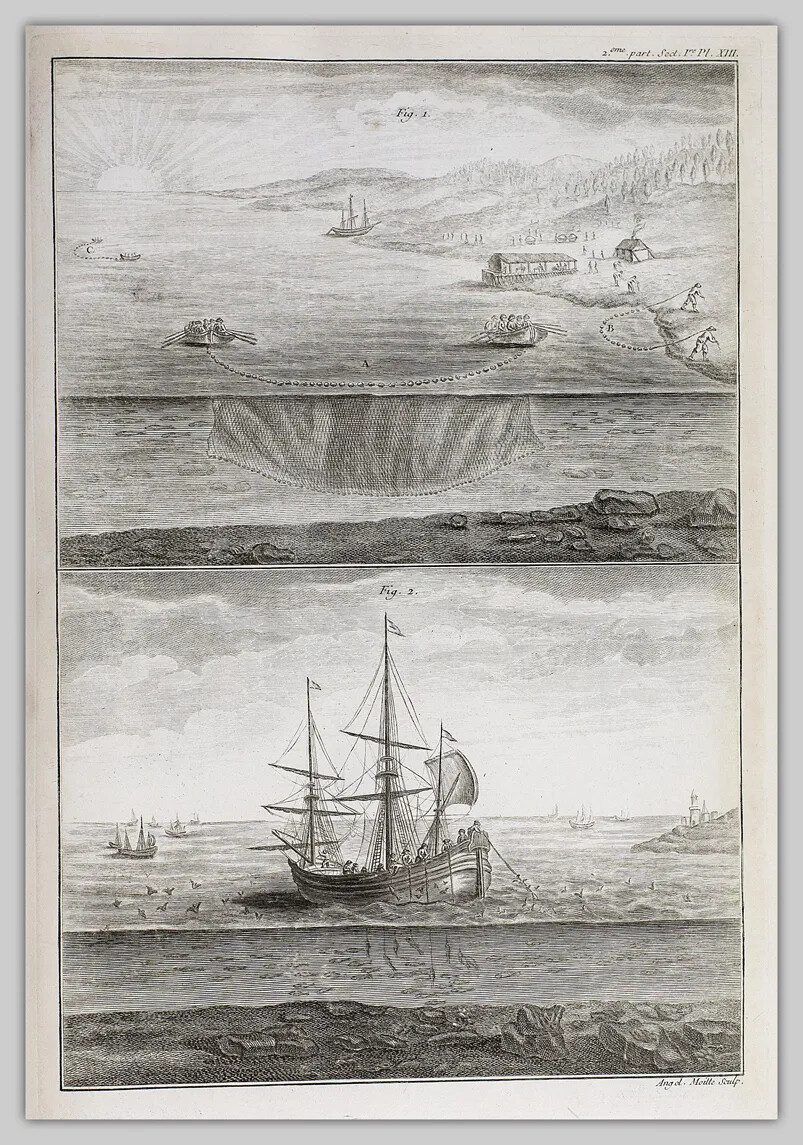

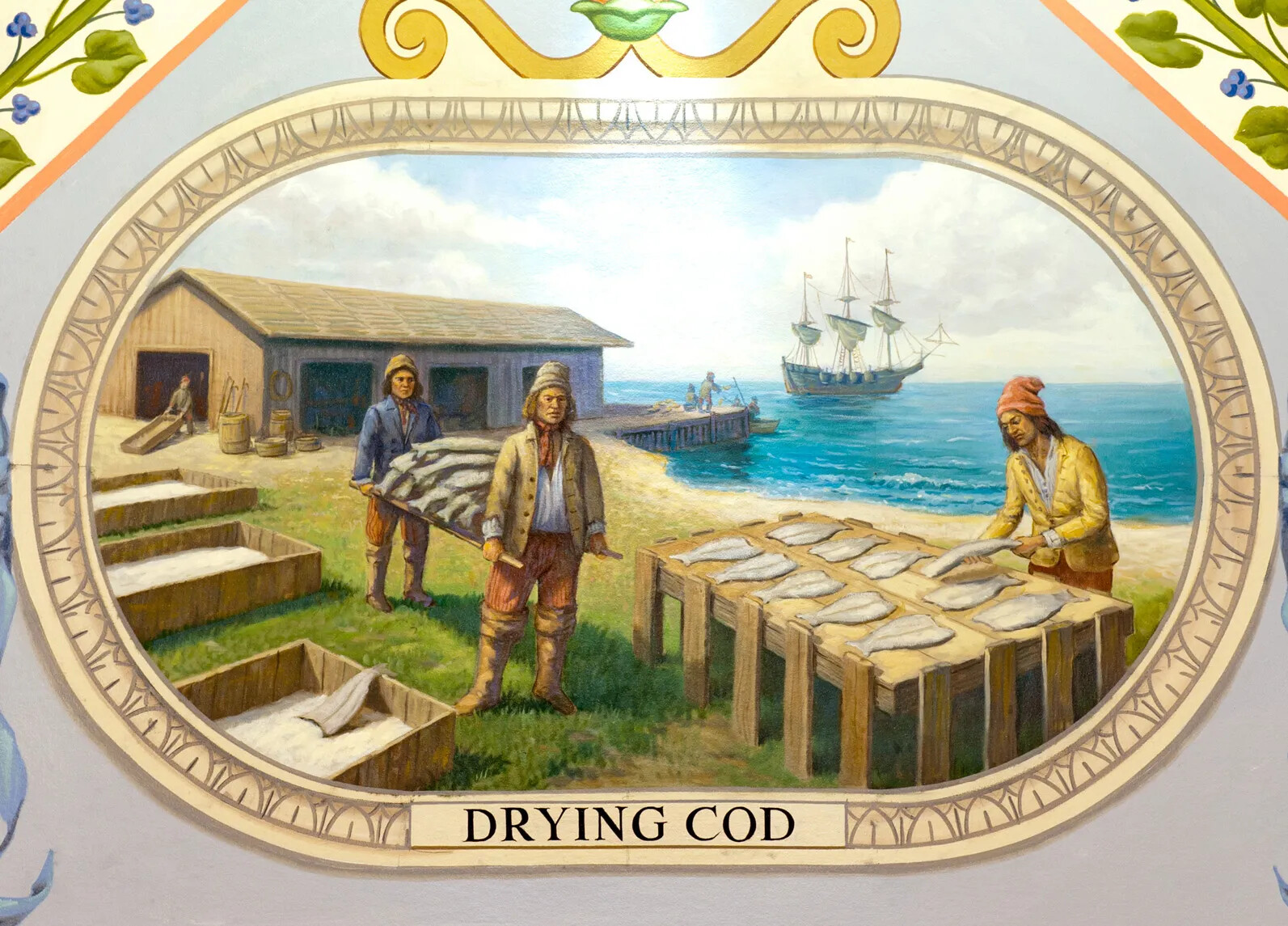

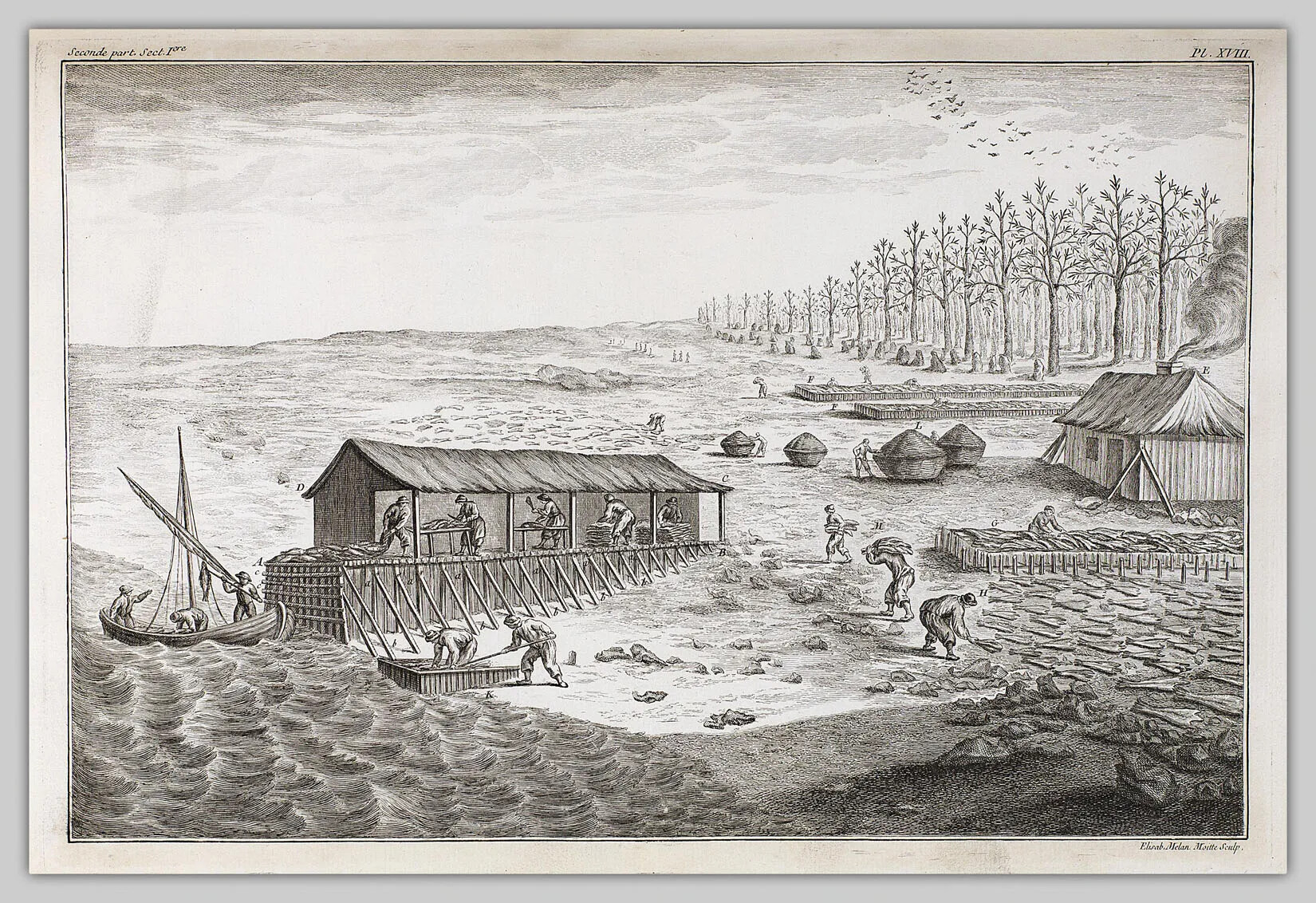

The fishermen used giant nets to scoop the fish out of the ocean and bring them onto the boat. Once they had a full load of fish, they would land their boats and carry all the fish onshore. Then they would lay the fish out in the sun on racks so the fish would dry out. This process would preserve the fish so they wouldn’t go bad. Once the fish were dried out, they were loaded onto ships and taken to Europe where the fish was sold to people to eat.

Caption:

This picture shows some of the ways that fishermen caught cod during the 1700s. The top of the picture shows catching cod with nets, and the bottom shows catching cod with lines dragging from the fishing boat. Cod fishermen used both methods.

Caption:

There were no refrigerators or freezers in the 1600s and 1700s. So fishermen had to preserve the codfish they caught before they shipped it back to England. They would salt it and lay it out in the sun to dry. This kept the fish from spoiling on the journey across the Atlantic Ocean. Cod was an important trade item because it was a popular food in England. This painting is part of a mural that hangs in one of the hallways of the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, DC.Caption:

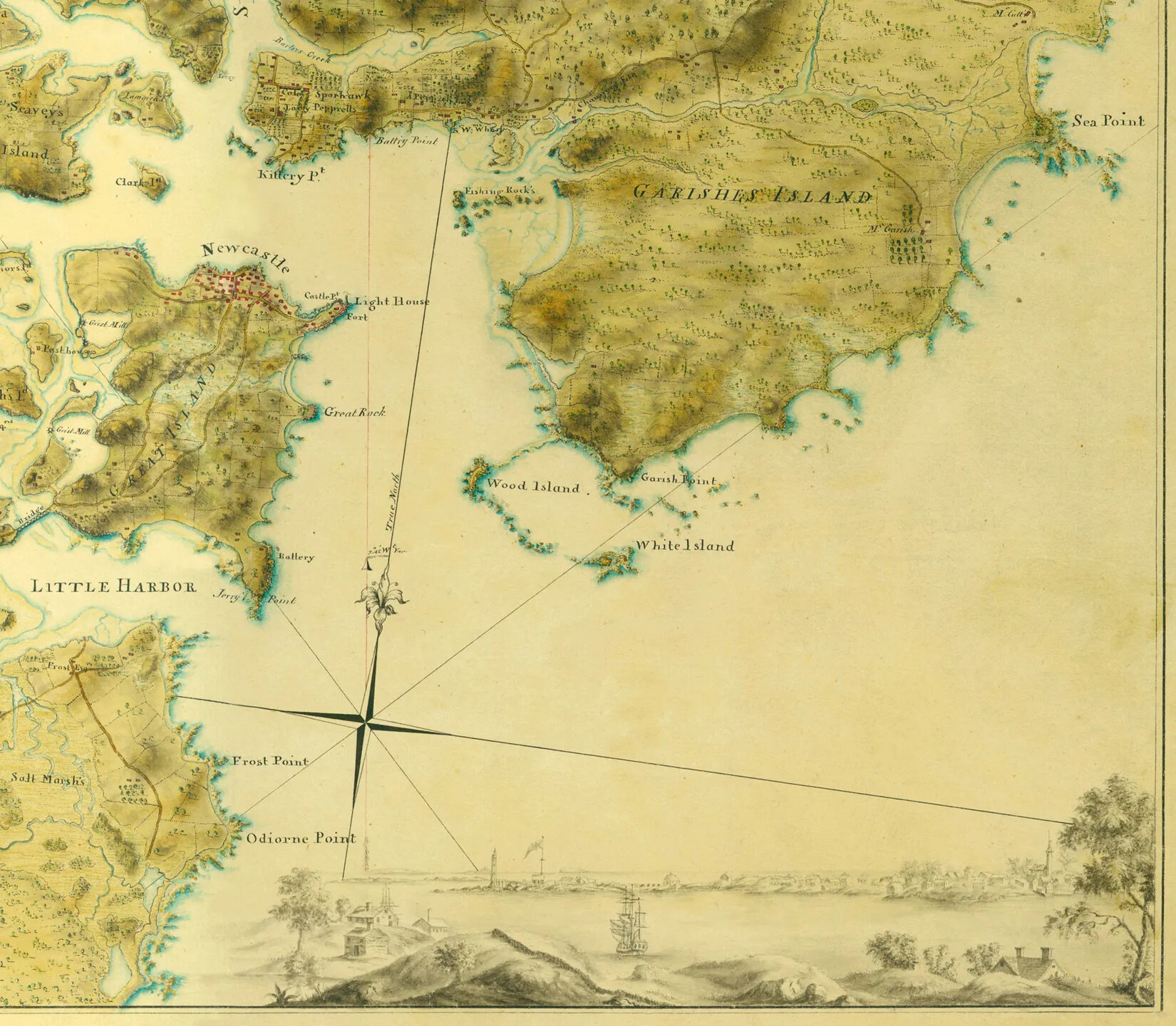

The first permanent European settlement in New Hampshire was at Odiorne Point in Rye. A group of English settlers led by a man named David Thomson came to the area mainly to fish. They built stone houses because they planned to stay year-round, even through the winter. Other Englishmen soon joined them and made their own settlements along the coast of New Hampshire and eventually inland.The earliest and largest fishing operation in New Hampshire was at a place called Pannaway on the seacoast. We know it today as Odiorne Point in Rye. The settlement was started in 1623 by a man named David Thomson.

Thomson wanted to fish in New England all year long, not just during the warm months like other fishermen were doing. When he arrived in New Hampshire with 20 other men, they built a large stone house to provide shelter for them in the colder months, and they fished year round.

Many of the settlers who arrived with Thomson stayed in New Hampshire permanently.

Caption:

David Thomson (sometimes spelled Thompson) founded the first permanent English settlement in New Hampshire, at what is now called Odiorne’s Point in Rye. Starting when he was still a boy, Thomson sailed to New England several times. He decided that the area near the Piscataqua River would be a good place to build a settlement. In 1623, he convinced a group of English businessmen to hire him to set up a year-round fishing station there. The settlers were supposed to send a lot of fish back to England to make money for the businessmen. They were also supposed to farm and set up a trading post. At first there were only 10 or 20 settlers, and they built a fort, some houses, and buildings to process the fish. In 1626, Thomson and his family moved to an island in Boston Harbor, called Thompson Island today. He died a few years later.Pannaway was not the only fishing operation in New Hampshire, though. Other fishing operations were set up on the Isles of Shoals and up and down the New Hampshire coastline. Most of them were seasonal, but many men came to work in them and then decided to remain in New Hampshire.

Fishing was one of New Hampshire’s most important industries for the next 150 years.

Caption:

This picture shows a fishing camp during the 1700s. Some workers caught the fish, using boats, nets, or weirs (underwater fences to trap fish). Others cut the fish, salted it, or laid it out to dry. Cod was an important natural resource on New Hampshire's seacoast during the colonial period. It was shipped back to England, where it was sold for profit.Fur

New Hampshire was home to many kinds of animals during this period, including hundreds of thousands of beavers. Beavers lived in the many lakes and rivers in the area but mostly inland, away from the seacoast. They were small animals, but they had beautiful, warm fur that people turned into clothing like coats and hats.

As beaver pelts became more and more popular in Europe, the demand for beaver fur became greater. Investors realized they could make a lot of money supplying furs to people in Europe.

Caption:

Beavers are mammals that live all over North America. They live on land but like wet environments, so they can be found in New Hampshire's wetlands. The Abenaki hunted beavers and used the pelts for clothing and blankets. When Europeans came to New Hampshire, they traded with the Abenaki for beaver pelts and hunted beavers themselves. Beavers were hunted so much that they almost became extinct, but now they are plentiful in New Hampshire again.In 1629, an English investor named John Mason started a company that was based in New Hampshire and supplied beaver furs for sale in England. His business was called the Laconia Company.

Mason sent more than 100 English men and women to New Hampshire. He told the settlers to break into small groups and build outposts along the rivers in the area.

It was Mason who named this region New Hampshire because he came from the county of Hampshire in England.

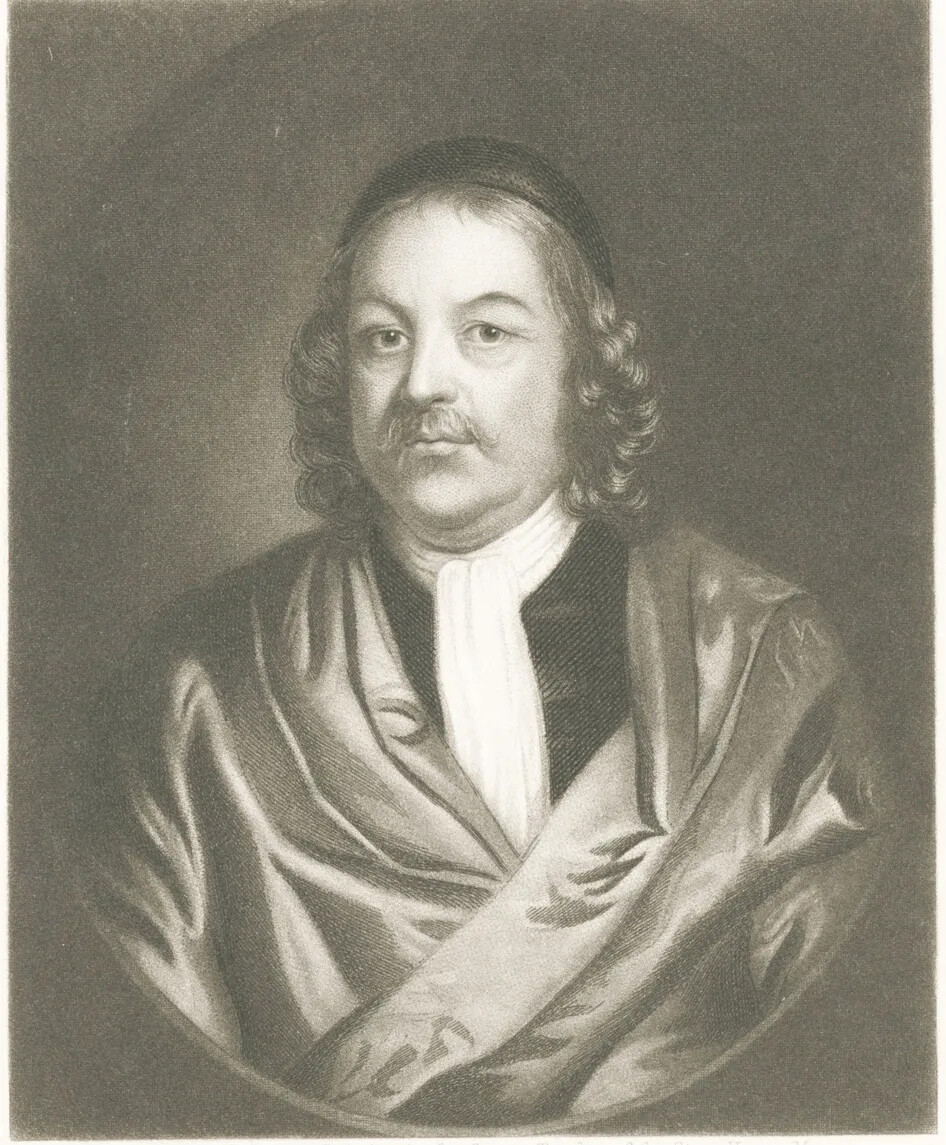

Caption:

John Mason was an English investor who gave New Hampshire its name. A naval officer and businessman, Mason had been the governor of the British settlement of Newfoundland, on the coast of Canada. He realized how important the fur trade was, so he started a company based in New Hampshire to supply beaver furs for sale in England. The business was called the Laconia Company. Mason sent English settlers to build outposts along the Piscataqua River and the other rivers around what is now Portsmouth. Mason named this area New Hampshire after Hampshire County, where he lived in England. Mason was planning to move to New Hampshire, but he died before he could leave England.

Caption:

This cartoon imagines Captain John Mason and Sir Ferdinando Gorges naming their colonies. They were both awarded a large land grant from the English king in 1622. Later they split the grant, and Gorges got the land that became Maine and Mason got the land that became New Hampshire. Mason named New Hampshire after his home in England, Hampshire County. Mason died before he could ever travel to New Hampshire.Caption:

Although other Englishmen came to New Hampshire in the early 1600s, the founder of New Hampshire was a man named Captain John Mason. He named this land after his home county in England, Hampshire. Mason planned to bring his wife and newborn baby with him when he and a group of settlers came to the New World in 1635. They planned to make money from all the fish in the waters off New Hampshire’s coast. They also thought they could trade with the Native Americans for beaver pelts, which were very popular in England. Unfortunately, Mason died unexpectedly before leaving England. For nearly 100 years afterward, his heirs fought to protect their claim to New Hampshire.

Caption:

During the 17th century, there was a big demand for beaver pelts in Europe. English settlers realized they could make a lot of money by trapping beavers and sending their pelts back to England. Some settlers hunted and trapped the beavers themselves. They also formed trade relationships with the Abenaki indigenous people. The Abenaki had a lot of experience and skill in trapping beavers. They traded pelts with the settlers in exchange for goods made in England, like metal tools.The settlers followed Mason’s instructions and started trapping thousands of beavers. After trapping beavers, the skins had to be removed quickly so the pelts didn’t spoil. Once the pelts were cleaned and dried, they were packed up and shipped back to England.

The settlers also formed partnerships with the Abenaki to help them trap beavers. The Abenaki brought beaver pelts to the settlers, and in exchange the settlers gave the Abenaki metal tools and other English objects the Abenaki found useful.

The English settlers and the Abenaki trapped so many beavers that soon there weren’t any left in that part of New Hampshire. In an effort to find more beavers, English settlers traveled far inland to places like the Lakes Region and the White Mountains.

By the middle of the 17th century, beavers were almost extinct in many parts of New Hampshire.

Forests

New Hampshire’s other major industry during the colonial period were its trees. When the first English settlers arrived in New Hampshire, it was covered by thick forests that were full of many different types of trees like birch, maple, chestnut, oak, and pine.

Wood was very important for the English settlers. They needed timber to build houses, meeting houses, and bridges. They used it to make wagons and boats. They built boxes and barrels out of wood to store food and other supplies. They used wood to make tools. They also needed a lot of wood to cook their food and heat their houses.

As more English settlers arrived in New England, they quickly chopped down the trees around them, especially in places where lots of people settled, like Massachusetts. New Hampshire had lots of trees, though, and people in New Hampshire cut them down and sold the wood to people in Massachusetts to make money.

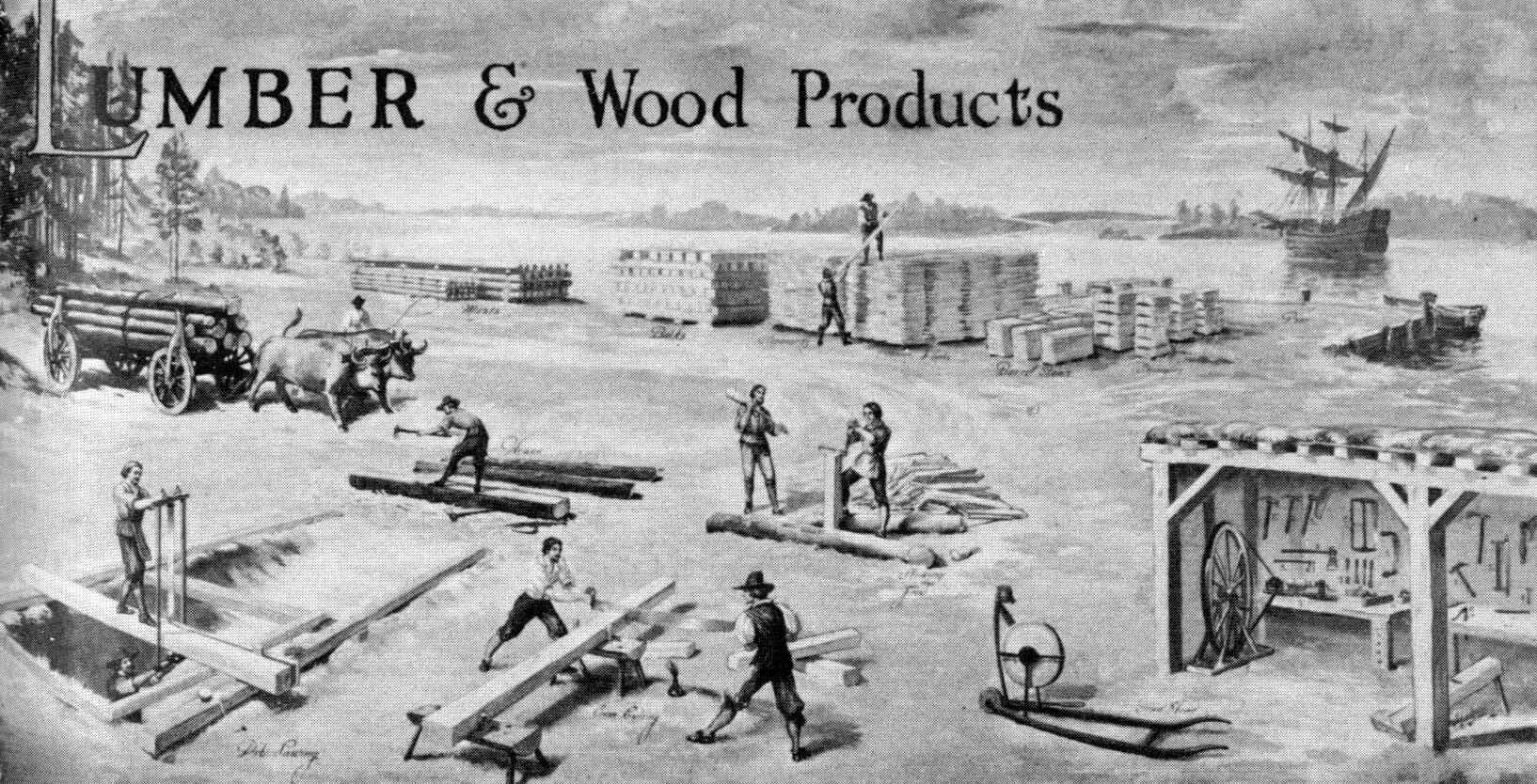

Caption:

This illustration shows the types of work that English settlers in the timber industry might have done. What do you notice about the kinds of things they may have built with the timber? How did they get the logs from the forest to their workshops? What did they do with the extra timber?

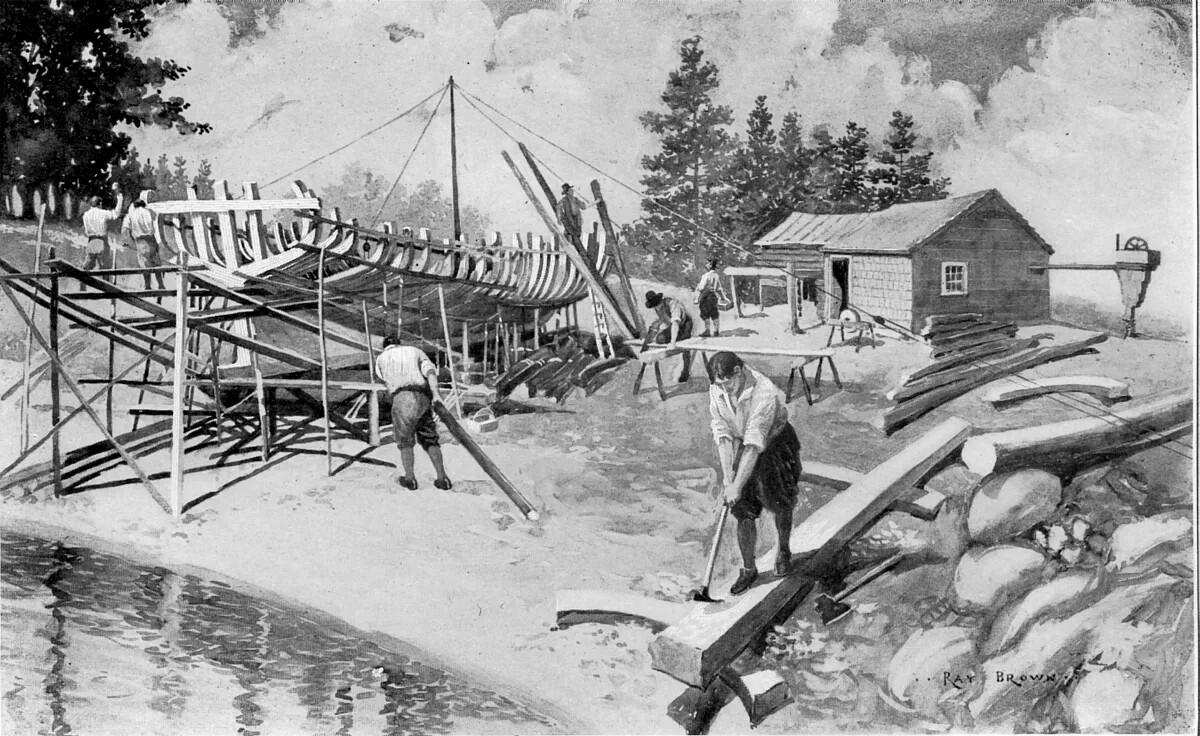

Caption:

Shipbuilding has been an important industry in New Hampshire for a long time. During the settlement era, New Hampshire had lots of forests that provided wood to build ships. Ships were very important for England's navy. England also needed a lot of ships to carry natural resources from its colonies and goods to its colonies. New Hampshire also had an important port, Portsmouth, where ships could sail from. Today, submarines are built at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard.New Hampshire also supplied wood to build ships. Ships were very important to the early settlers because they had to ship all their products, like fish and furs, to England.

People also sailed on ships themselves to cross the Atlantic Ocean to Europe and back.

Many of the fishermen who came to New Hampshire had experience building ships. They set up shipbuilding operations along the seacoast, especially in a new settlement they built called Strawbery Banke, which we know today as Portsmouth.

Portsmouth had a deep harbor, which made it easier to build and launch ships that were big enough to sail the Atlantic Ocean. It was also at the mouth of four rivers that went inland.

Portsmouth became an important center for shipbuilding in America.

Caption:

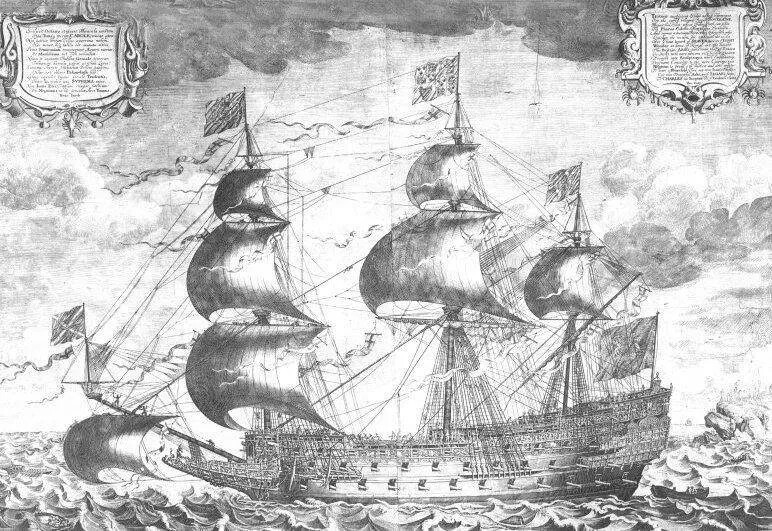

This image shows two groups of white pine trees. The group on the left is mature at about 60 years old and is being clear-cut. The group on the right is younger and won't be harvested for 20 or 30 more years.New Hampshire’s forests also provided tall white pine trees used for masts on ships. Masts were used to hold the sails on a ship in place. At this time, all ships were sailing ships, which meant they were powered by wind in their sails pushing them forward.

The tall white pine trees used for ships’ masts were sometimes more than 200 feet tall and so wide that they were strong enough not to break when the wind pushed against the sails. Most ships that sailed on the Atlantic Ocean at this time had three or four masts, and the masts had to be replaced every 15 or 20 years.

With all the English ships sailing in the 17th century, there was a lot of demand for mast trees. Luckily, New Hampshire had a big supply of them.

Most of the mast trees were used for the ships of the British navy. England had a long tradition of having a strong navy because England itself is an island. Having a strong navy was how England protected itself from other countries.

In the 17th century, the British navy was getting bigger, as English explorers traveled around the world claiming more places as British colonies.

The British navy also started building ships that were bigger than ever before. By the end of the 17th century, one ship in the British navy might have as many as 20 masts!

Caption:

The HMS Sovereign of the Seas was a large, powerful British warship built in 1637. It fought in several important naval battles. It was decorated with elaborate designs and carried 102 bronze guns. It had three decks and three tall masts, all made of wood. The Sovereign of the Seas burned in 1697.

Caption:

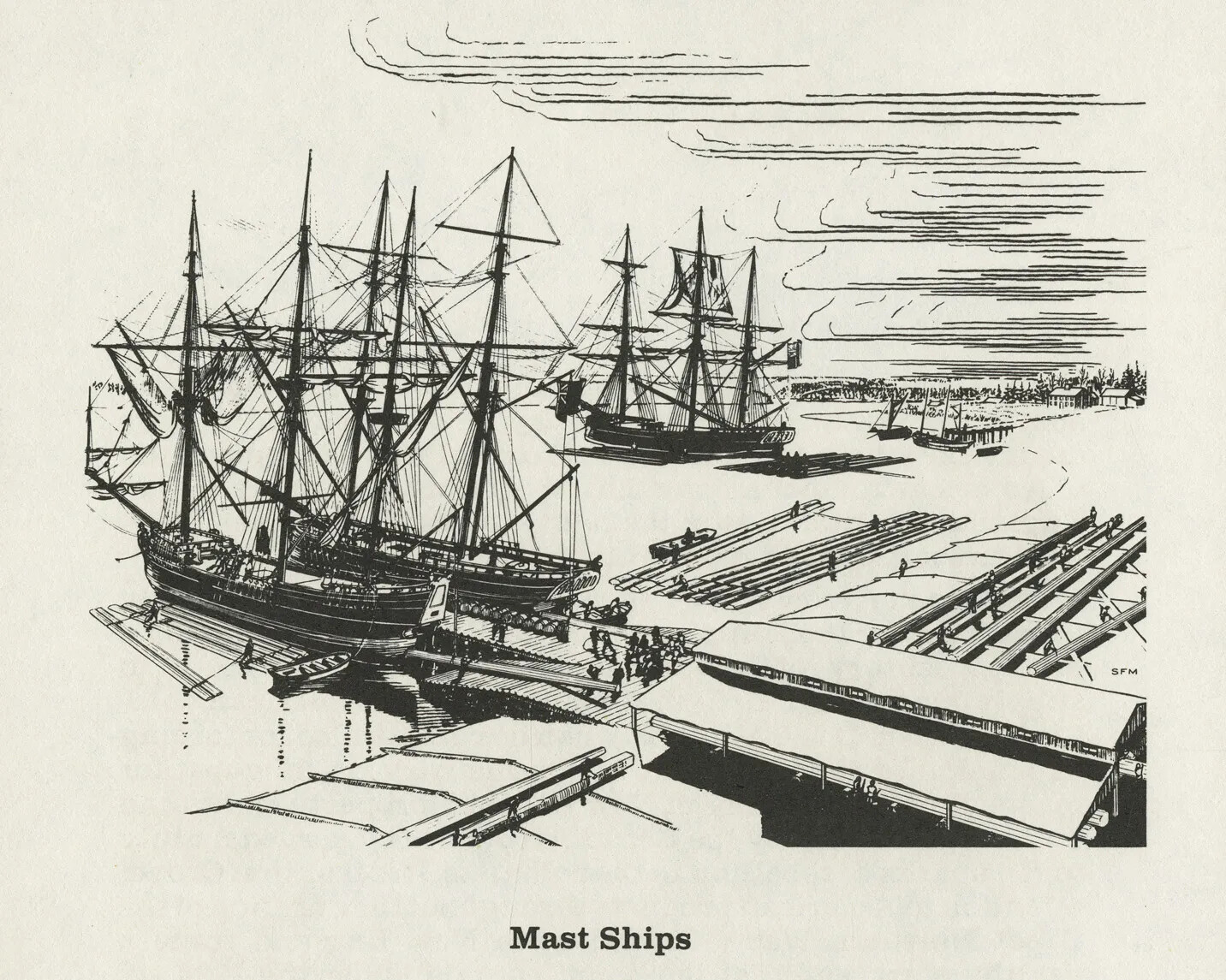

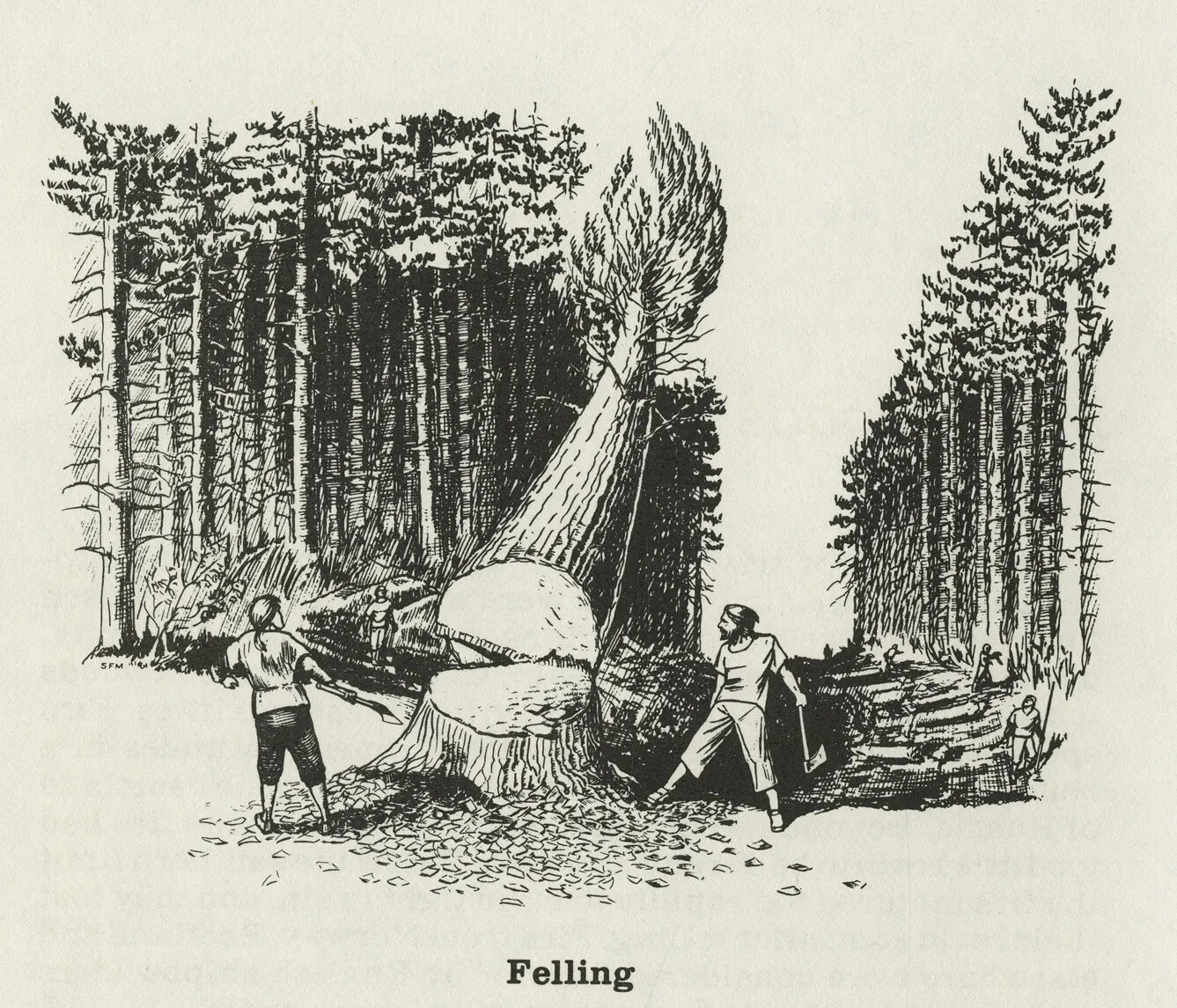

Shipbuilding was an important industry for the English people who settled New Hampshire. New Hampshire had an important natural resource, white pine trees, that were used to make ships' masts. Masts are the tall poles on ships that carry the sails. The trees had to be cut down and carried from the forest all the way to the harbor, where the shipyard was. Then they were used to build the ships. Notice how many masts the ships had and how tall they are!It was a lot of work to cut down these huge trees and move them out of the forest. Several men would use axes to chop through the trunk of the tree and bring it to the ground. Then they would cut off the branches so just the trunk was left. Once they had cut down several trees, they tied the trunks together and hitched them to a team of oxen.

The oxen pulled the trunks through the forest until they reached a river. The trunks were then moved into the river and floated downstream until they reached a harbor near the ocean. Then the trunks were either used to build ships right there in the harbor, or they were loaded onto specially built mast ships that could carry the giant trees in their holds. The ships sailed to England or a port where ships were built, and the trees were used to build or repair the sailing ships.

Once the mast trees were all used up in one area of New Hampshire, the English then pushed further inland to new parts of the colony to find more pine trees of the right height and strength to be ships’ masts.

The paths that the oxen cut through the forests as they dragged the trees to the rivers became almost like roads. In fact, many towns in New Hampshire turned those paths into roads when the towns were settled. Some of those roads still exist today. They have names like Mast Road or Mast Street. These roads are hundreds of years old and were once used for this early New Hampshire industry.

Caption:

Shipbuilding was an important industry for the English people who settled New Hampshire. New Hampshire had an important natural resource, white pine trees, that were used to make ships' masts. Masts are the tall poles on ships that carry the sails. "Felling" is the process of cutting down trees. It was a lot of hard work to cut down the tall pine trees and transport them through the forest and to the harbor, where the shipyard was.

Caption:

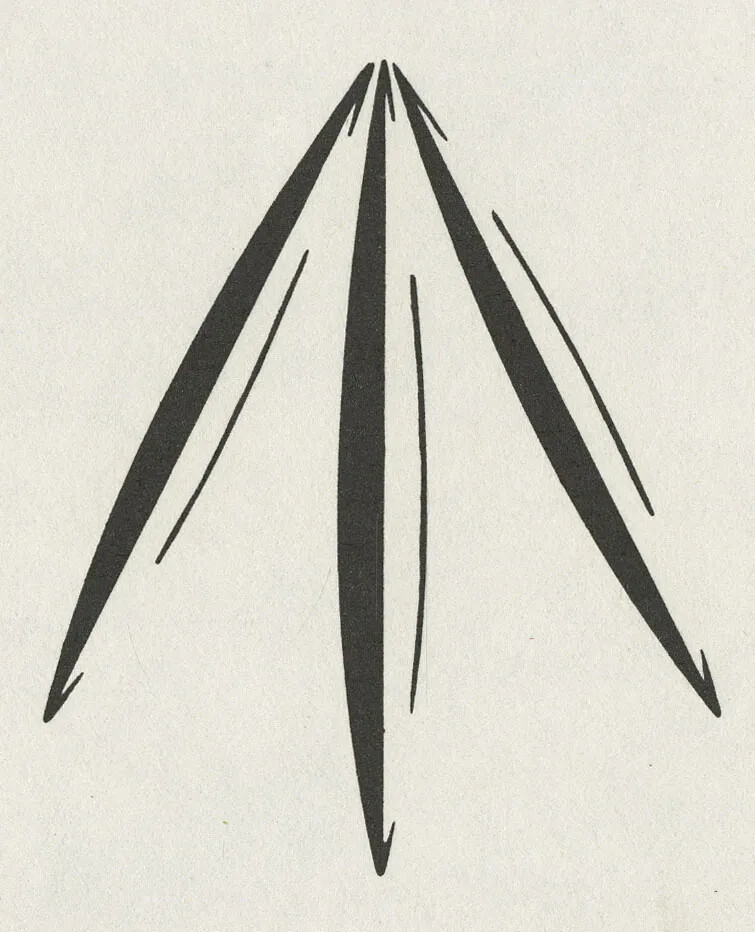

One of New Hampshire's most valuable resources during the colonial period was its white pine trees. These tall, strong trees made perfect ships' masts. During the 1700s, the British navy needed thousands of these trees for their ships. The British government passed a law that said all white pine trees in New Hampshire of a certain size belonged to the king, even if the trees were on private land. British officials would ride around the countryside and use an axe to mark the best trees with this mark, the "king's broad arrow." Any trees with this mark couldn't be used to build the colonists' houses and bridges. They started to become angry with the royal officials who marked these trees. This was one of the issues that pushed Americans closer to revolution.Most of the trees used as ships’ masts on English ships in the 17th century and 18th century came from New Hampshire. In fact, the colony became famous for its mast trees, and the British navy seemed to need more and more of them every year.

The British government started passing laws in the late 1600s to claim the mast trees for themselves. British officials carved a mark on all the mast trees they could find. The mark, called the King’s Broad Arrow, meant only the British government could use those trees. The colonists in New Hampshire were not allowed to cut them down for themselves.

The people of New Hampshire didn’t like this law, but they had to follow it or they would be in trouble with the government.

These three early industries brought many people to New Hampshire. Some of them came just to make money and then returned home. But many people grew to love New Hampshire and decided to make their homes here. They built more permanent settlements that over time grew to be towns, which still exist today.

Caption:

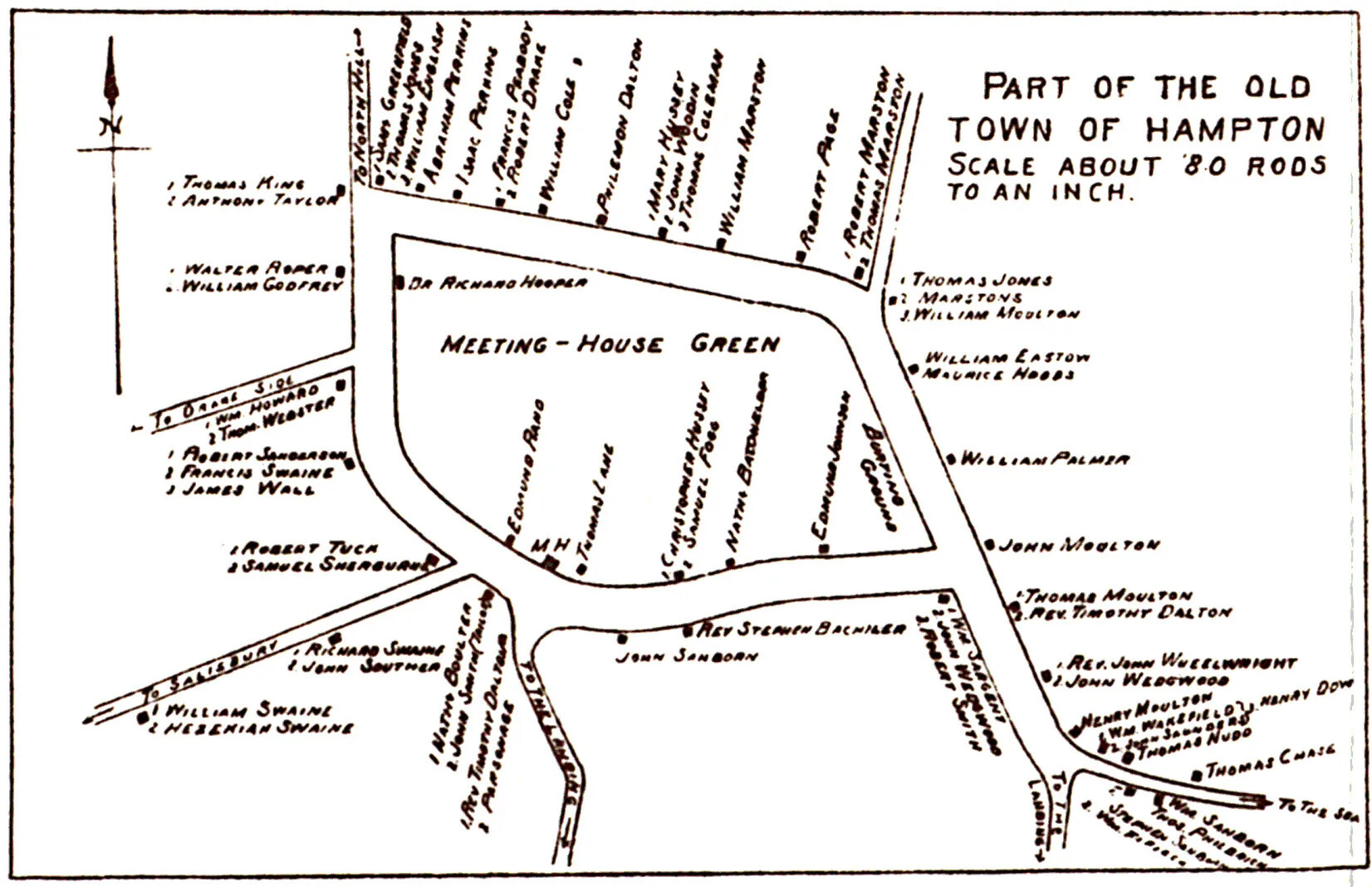

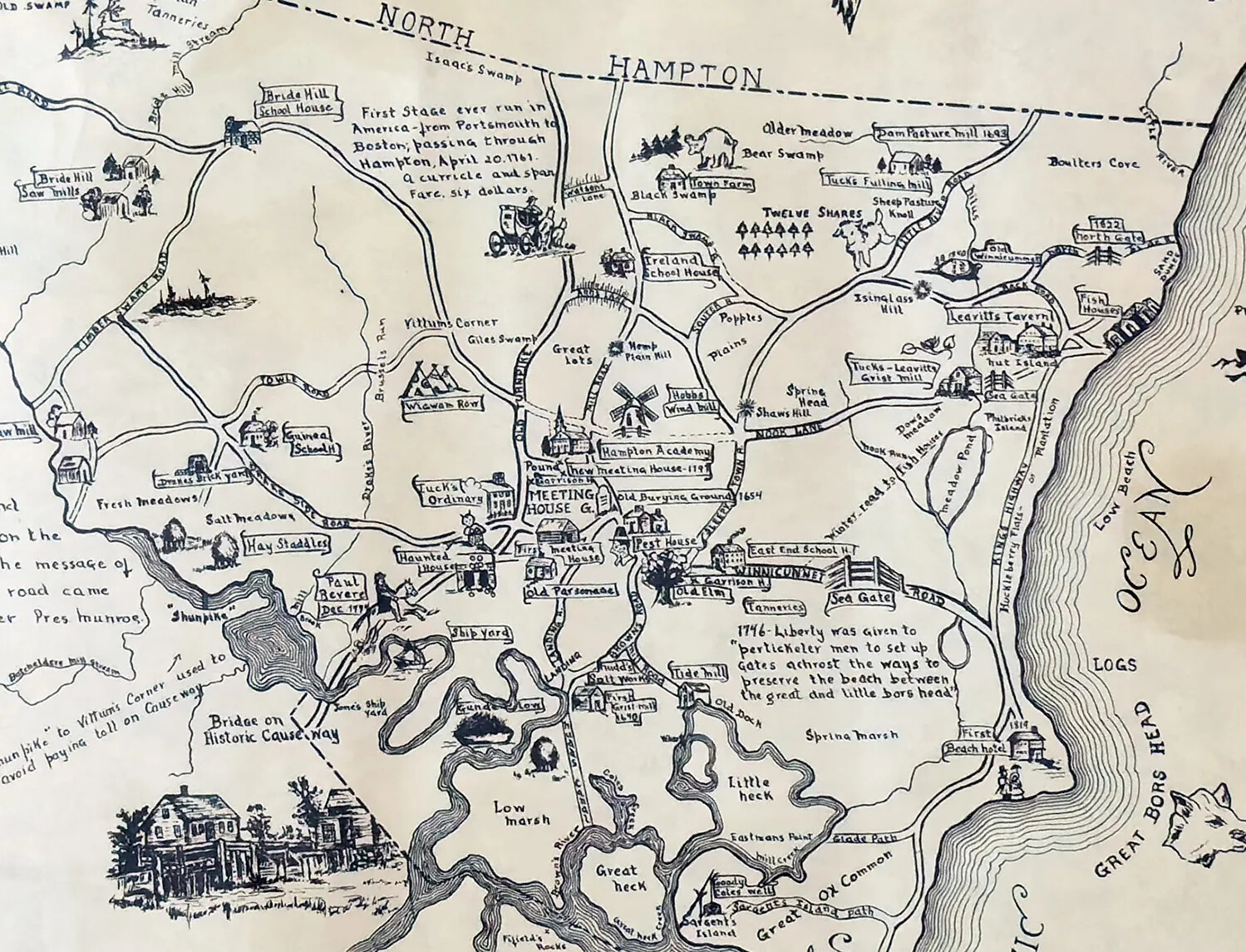

English settlers established three important industries in New Hampshire starting in the 1630s—fish, fur, and forests. These industries were successful, so more and more settlers came to make money. Some of them stayed and formed towns. This map shows and early settlement that became the town of Hampton, New Hampshire.Let's Review!

What are the big ideas in this section?

The Three F's

New Hampshire’s three early industries were based on fish, fur, and forests. These three industries brought many people to New Hampshire. Some came to make money and then returned to England, but others decided to stay in New Hampshire and build settlements.

Fish

An important natural resource in New Hampshire were the many fish in the ocean, especially cod. Fisherman set up the first settlements in New Hampshire so that they could catch fish, dry the fish, and ship the fish to sell in Europe. Fishing was an important industry for the next 150 years in New Hampshire.

Fur

As beaver pelts became popular in Europe the industry around beaver fur grew. Beaver trappers collected pelts to ship back to England. They also developed partnerships with the Abenaki to help trap more beavers. However, soon they trapped so many beavers that by the middle of the 17th century beavers were almost extinct in parts of New Hampshire.

Forests

During the colonial period, a major industry was providing wood for people who used it to build structures and to burn for heat and cooking. Portsmouth used wood to become a center of shipbuilding. Most especially, New Hampshire’s white pine trees were cut down for masts for warships for the British navy during this time.

Caption:

This watercolor drawing shows an Abenaki couple wearing traditional Abenaki clothing in the 1700s. It was made by a Canadian artist. The Abenaki homeland, N'dakinna, includes part of what is now known as Quebec in Canada. During the period of English settlement, many Abenaki moved to Quebec from New England. They were pushed out by war and settlers taking their land. Today thousands of Abenaki live in Canada. The Abenaki are one of the indigenous groups recognized as a First Nation by the Canadian government.The Abenaki Response

How did the Abenaki react to the English settlers?

When Martin Pring visited New Hampshire in 1603, there were more than 20,000 Abenaki living here, many of them along the seacoast. They lived in small tribal groups, and their lives were shaped by the traditional practices that had developed over thousands of years. They had complex communities that interacted with one another throughout the region.

Caption:

Martin Pring was the first English explorer to sail up the Piscataqua River in New Hampshire. He was only 23 years old in 1603 when he led an expedition to New England to find sassafras. Sassafras is a plant that people used as medicine. Pring and his crew explored the coast of Maine and then landed near what is now Portsmouth. They sailed 10 or 12 miles up the Piscataqua River. He didn’t find any sassafras there, though, so he continued south to Cape Cod. He found a lot of sassafras and met with the indigenous people who lived there. He sent a whole boatload of sassafras back to England, along with information about all of the plants and animals that he saw in New England. His reports helped convince English businessmen that they could make money by sponsoring settlements there. Pring continued to explore North America and Asia after this successful voyage.The Abenaki relied on the natural resources around them to make the things they needed to survive in New Hampshire. They were careful to protect the balance of the world, so they only hunted or fished as much as they needed to live. When they killed animals, they honored the animals for their sacrifice and made sure to use every part of the animals so nothing was wasted. They also grew crops and gathered berries and nuts to eat.

The Abenaki shared their culture through stories and music. They also made beautiful baskets and jewelry from quahog shells, which were called wampum.

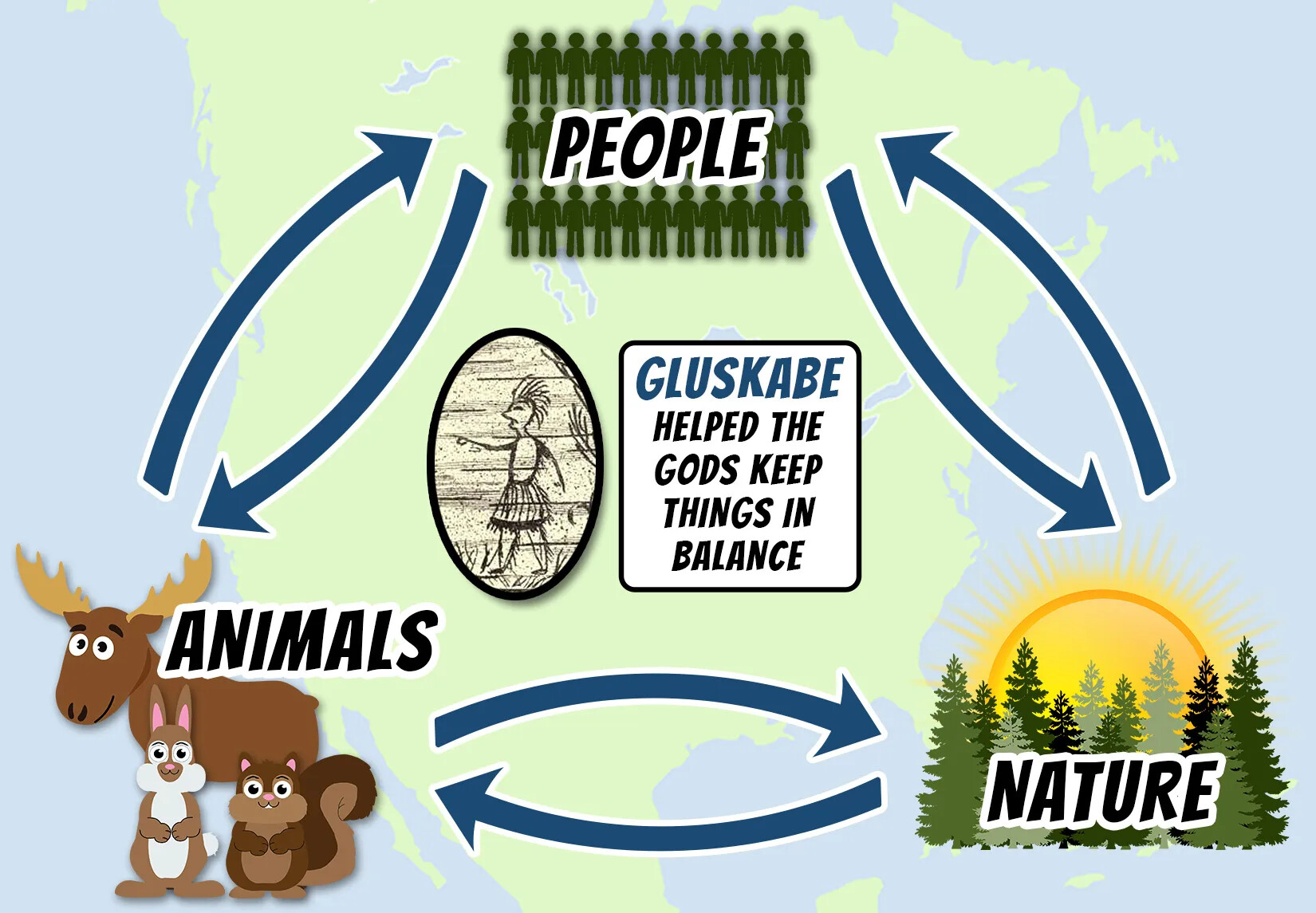

Caption:

The Abenaki believe that everything in the world has a spirit, including plants, animals, the land, and the elements. All spirits are important, and all spirits' needs should be respected. Everything in the world is connected through these spirits. It's important to keep all of these spirits in balance. That is why the Abenaki people believe that you should only take from the earth what you need. It is also why they thank the animal for its sacrifice after a hunt.

Caption:

Abenaki storyteller Joseph Bruchac tells the story of how Gluskabe created the Abenaki people.

Caption:

Starting in the 1500s or even earlier, European fishermen began to sail across the Atlantic Ocean to catch codfish off the eastern coast of Canada. They set up temporary fishing camps along the coast and caught as many fish as they could. They dried the fish in the sun or salted it to preserve it, and brought it back to Europe to sell. Soon they followed the fish down the coast to New England. Each summer, hundreds of fishing ships were anchored along the coast. Then the fishermen began to trade with the indigenous people for furs, which they could also sell in Europe. Through these interactions, the European fishermen also accidentally transmitted diseases to the indigenous people.The Abenaki who lived near the Atlantic Ocean sometimes interacted with fishermen from Europe, who sailed to New England to catch the huge schools, or groups, of fish in this part of the ocean.

These fishermen accidentally brought diseases with them and gave the diseases to the Abenaki. The fishermen had been exposed to these diseases in their home countries, so they had some immunity, or protection, from getting sick. But since the Abenaki had never encountered these diseases before, they got very, very sick, and many of them died.

Between 1616 to 1619, there was a pandemic among the Abenaki living near the seacoast, and thousands of them died from these European diseases. In all, less than 25% of the Abenaki in the seacoast region survived. The pandemic affected the Abenaki in the rest of New Hampshire too, but it hit the seacoast area the hardest.

It was a terrible time for the Abenaki. Those who survived lost many family members and friends to the pandemic. They also grew unsure of how they should react to the English people who began arriving in New Hampshire to stay.

Should they welcome them and try to live in peace with them? Or should they fight them until they made the English leave?

Caption:

Before English colonists established permanent settlements in what is now called New Hampshire, there was a terrible plague that killed thousands of indigenous people. European traders brought the plague to Abenaki people living along the Saco River in 1616. It spread all throughout New England. By 1619, more than 75% of the Abenaki living in seacoast region had died. This period is known as the "Great Dying."Caption:

The Europeans who visited New England accidently brought with them diseases like small pox and chicken pox. Unfortunately, thousands of the Abenaki caught these diseases and became sick. Since the Abenaki were not used to European diseases, their bodies had no resistance to the infections. More than three-quarters of the Abenaki became sick and died from these diseases, and sometimes diseases wiped out entire villages of Native Americans.The Abenaki looked to their sachem Passaconaway for guidance. Passaconaway told the Abenaki that he had dreamed the English settlers would stay in New Hampshire no matter what. He advised the Abenaki to accept the English and not fight against them. He hoped that they could all live peaceably together.

For most of the 1600s, the Abenaki and the English did get along with one another in New Hampshire, but the English brought many changes with them, including new industries that upset the balance of the natural world.

Caption:

Passaconaway, also called "Papisseconawa," was the leader of the Penacook people, an Abenaki tribe living in the Merrimack Valley. He lived during the time of English exploration and settlement of the Abenaki homeland, called N’dakinna. The Penacook were part of a large and powerful group of Abenaki tribes, called a confederacy. Passaconaway was a very important and respected leader. The Abenaki believed that he had special powers, like being able to see the future, to control the weather, and to transform into the shapes of animals, like bears. His name means "child of the bear" in the Abenaki language. When the English arrived, Passaconaway encouraged the Abenaki to live peacefully with them. He believed this was the best way to keep his people safe and preserve their culture and way of life. It is hard to know exactly when he was born and exactly when he died, but legend has it that he lived to be 120 years old!

Caption:

Passaconaway, also called "Papisseconawa," was the leader of the Penacook people, an Abenaki tribe living in the Merrimack Valley. He lived during the time of English exploration and settlement of the Abenaki homeland, called N’dakinna. The Penacook were part of a large and powerful group of Abenaki tribes, called a confederacy. Passaconaway was a very important and respected leader. When the English arrived, Passaconaway encouraged the Abenaki to live peacefully with them. He believed this was the best way to keep his people safe and preserve their culture and way of life. We don't know for sure that this is what Passaconaway looked like. This is an illustration from a book printed in the 1800s.How did life change for the Abenaki after the English settlers arrived?

The Abenaki and the English lived in peace with one another for most of the 17th century. The arrival of the English settlers brought big changes to the Abenaki’s traditional way of life, though.

The pandemic killed many Abenaki even before the English began to arrive in large numbers. Early English settlers wrote about finding empty Abenaki villages because all the people had died of disease. No one knows exactly how many Abenaki died, but some people believe it was more than 75% of the population. That means for every four people, three of them died in the pandemic.

The survivors had to organize themselves into new family groups and tribes. Many of the Abenaki sachems died as well, so the Abenaki did not have leaders to guide them through these hard times.

Caption:

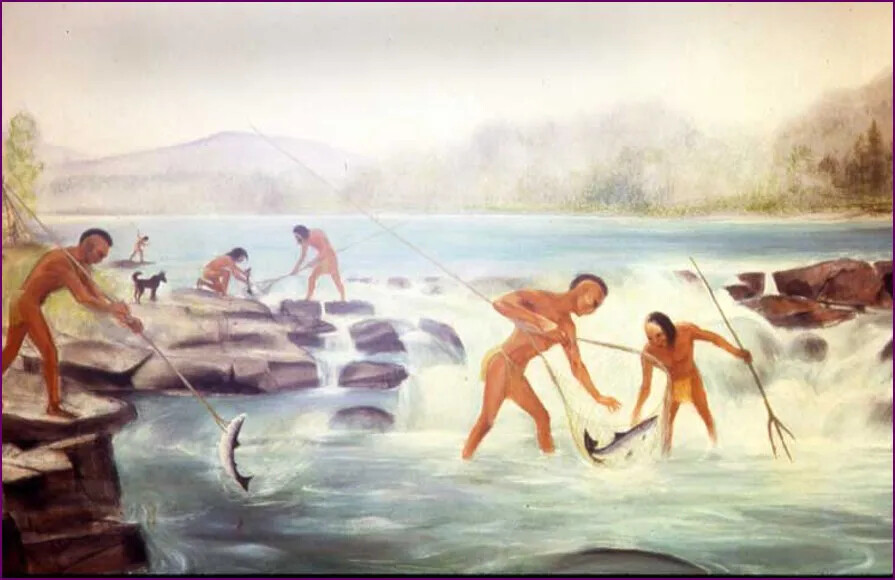

People have fished New Hampshire's fast-moving waters for thousands of years. Amoskeag Falls on the Merrimack River is one example of an excellent fishing spot. Each spring, bands of Abenaki would gather at this place to fish. They used spears and nets made from natural materials to catch the fish. This painting was created in the 1970s as part of a mural that now hangs in the Hooksett, NH, town hall.When the English first arrived in New Hampshire in the 1620s and 1630s, the Abenaki helped them adapt to life in New Hampshire.

The Abenaki taught them what crops would grow in New Hampshire’s soil and showed the English many different ways to use the natural resources available to them. The Abenaki shared with the English how to build both dugout canoes and birch bark canoes. They taught them how to use snowshoes to travel in winter. They showed them how to make maple syrup. They helped the English learn what plants were safe to eat and how to hunt the animals in New Hampshire. They told the English about the best places to trap beavers. The Abenaki also shared with the English what they knew about the land further away from the seacoast, where there were large lakes and great mountains.

Without the help of the Abenaki, the English might not have survived when they first came to New Hampshire.

In return, the English introduced the Abenaki to new tools and objects made from metal, like cooking pots, axes, knives, and guns. Metal was stronger and tougher than anything the Abenaki could find in nature.

The Abenaki saw how useful metal objects could be for them, so they traded with the English for things made out of metal.

Caption:

This type of axe is called a trade axe. The English manufactured thousands of axes to trade with Native Americans in exchange for animal furs. They also sometimes gave the axes as gifts. Metal axes cut things more quickly than stone tools.

Caption:

English explorers first met the Abenaki people in the late 1500s and early 1600s. The English and the Abenaki traded with each other for items like beaver pelts, wampum, and metal tools like ax heads. Many people think this image shows an explorer named Bartholomew Gosnold trading with Native Americans in what is now Massachusetts. Other people think it shows a different Englishman trading with Native Americans in what is now Newfoundland, Canada. It is probably not a very accurate image of what the indigenous people looked like. But it does give you an idea of early meetings between indigenous people of New England and English explorers.The Abenaki also became trading partners with the English in trapping beavers and catching fish. The Abenaki knew the land better than the English did, and they had experience with the animals. But normally the Abenaki would only catch as many animals as they needed, and they would make sure to use all parts of the animal. This practice prevented them from killing too many animals at any one time because they cared about balancing what was good for nature as well as what was good for them.

The trade with the English changed this pattern because the English wanted so many beavers and so much fish all at once, as much as the Abenaki could catch. The animal population went down because more animals were dying than being born. For the beavers, the English wanted only the pelts, so the rest of the animal was wasted. Catching so many beavers and so many fish upset the balance of nature that the Abenaki valued.

As more English settlers arrived, the Abenaki were pushed off their lands. The Abenaki moved west to go further inland and join other tribes of Abenaki. But as the English pushed their settlements further inland, the Abenaki were again pushed even further west and north.

The English settlers believed they owned the land on which they built their communities, and they did not want the Abenaki to live near them. The Abenaki were used to sharing natural resources with others, so they did not understand why the English wanted them to leave. Many of the English settlers did not respect the Abenaki’s culture or traditions either.

Caption:

Abenaki villages were always built close to a water source. In the village, the wigwams were built in a half-circle pattern, with a fire pit in the center. Around the edges of the village, the Abenaki planted crops to grow food. Some villages were very large, with hundreds of people living there.Let's Review!

What are the big ideas in this section?

Abenaki People

In 1600 the more than 20,000 Abenaki people who lived in New Hampshire had complex communities. They relied on natural resources to make what they needed. They protected the balance of the world by only taking as many natural resources from the earth as necessary. They shared their culture through stories, art, and music.

Pandemic among the Abenaki

In the 1600s fisherman from Europe brought diseases and accidentally gave them to the Abenaki. The Abenaki had never been exposed to these diseases before. More than 75% of the Abenaki in the seacoast region died as a result. Their communities were devastated.

Passaconaway, Abenaki Leader

In the early 1600s, the Abenaki’s sachem Passaconaway advised them to live peaceably with the English. He thought the Abenaki needed to accept that the English explorers and settlers were staying even if they brought much change.

Abenaki and English Living Together

At first the English and Abenaki traded and shared information with each other. The Abenaki helped the English survive in New Hampshire, and the English gave the Abenaki tools and objects of metal. However, as more English settlers arrived the Abenaki were pushed off their lands, which led to conflict.

The First Four Towns

Where did the English first settle in New Hampshire?

For the first 100 years of New Hampshire’s colonial period, the English settled in the seacoast region and stayed within 40 miles of the coast. In these years, four communities of English settlers were created. These communities became New Hampshire’s first four towns.

Caption:

This map shows the location of New Hampshire's first four English towns: Dover, Exeter, Hampton, and Portsmouth.Dover

In 1623, two brothers named William and Edward Hilton founded a settlement on the Piscataqua River, which they named Hilton’s Point. The Hilton brothers had come to New Hampshire to work on the fishing operation run by David Thomson, but once they got here they decided to head out on their own instead.

Hilton’s Point changed its name many times, but most people called it by the Abenaki name for the area: Cocheco. It eventually became known as Dover.

Dover is the oldest permanent settlement in New Hampshire. At the time it was founded in 1623, there were only a few other permanent settlements in the British colonies in America.

Caption:

Edward Hilton and his brother, William, founded one of New Hampshire’s first four English towns, Dover. The Hilton brothers were fishmongers in London, England. They came to New Hampshire with David Thomson as part of his fishing settlement, but the Hilton brothers set up their own fishing operation on the Piscataqua River in 1623, which they named Hilton’s Point. Most people called this settlement Cocheco, after the Abenaki name for the area. It eventually became known as Dover.Caption:

David Thomson (sometimes spelled Thompson) founded the first permanent English settlement in New Hampshire, at what is now called Odiorne’s Point in Rye. Starting when he was still a boy, Thomson sailed to New England several times. He decided that the area near the Piscataqua River would be a good place to build a settlement. In 1623, he convinced a group of English businessmen to hire him to set up a year-round fishing station there. The settlers were supposed to send a lot of fish back to England to make money for the businessmen. They were also supposed to farm and set up a trading post. At first there were only 10 or 20 settlers, and they built a fort, some houses, and buildings to process the fish. In 1626, Thomson and his family moved to an island in Boston Harbor, called Thompson Island today. He died a few years later.

Caption:

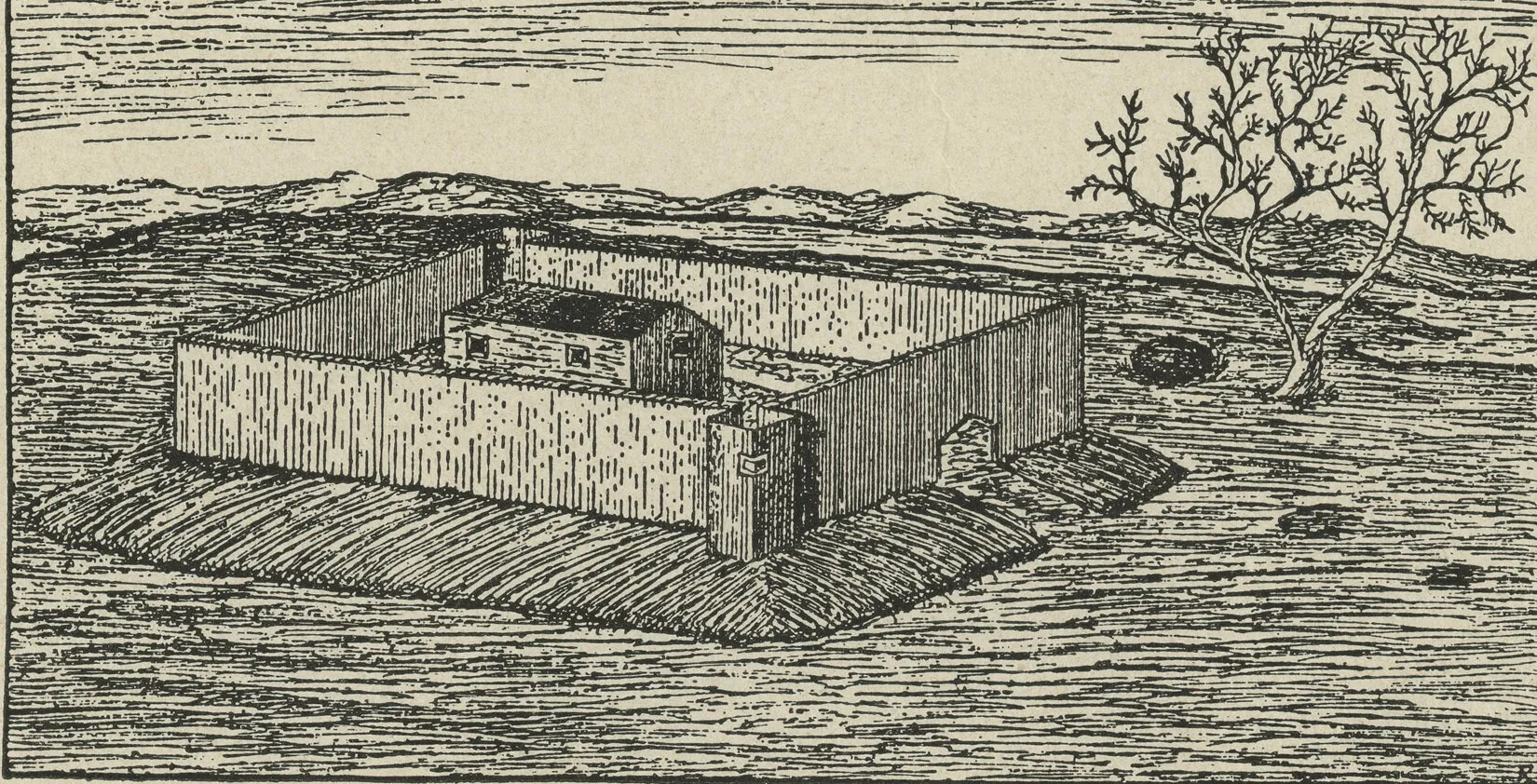

Dover is one of New Hampshire's first four English towns. In fact, it is the oldest permanent English settlement in New Hampshire. It was founded in 1623 by brothers Edward and William Hilton. The settlement was located on the southern tip of Dover Neck, a piece of land that juts into the water where the Piscataqua River and the Great Bay meet. This drawing of the first meeting house built on Dover Neck was made much later.

Caption:

The Damm Garrison House is the oldest garrison house left in New Hampshire. It was built in 1675 by William Damm, who lived in Dover, NH. Garrison houses were homes for families that were built like forts. For example, there were slits in the walls for muskets to shoot through, and the door was extra strong. Colonial towns usually had a garrison house in each neighborhood. If settlers needed protection, they would run to the garrison house and stay inside until it was safe. You can visit the Damm Garrison House today at the Woodman Museum in Dover.At first, not many people settled in Cocheco, but in the 1640s, lots of people started to move to the area. They built big log houses, including a garrison house for protection from the Abenaki. The people who lived there trapped beavers, cut down mast trees, and farmed the land around them.

Portsmouth

The Laconia Company, which was a business run by John Mason, was based on the coast of New Hampshire in a small settlement known as Strawbery Banke because strawberries grew there. The Laconia Company went out of business after just a few years, but many of the people who lived at Strawbery Banke decided to stay there instead of returning to England.

The settlement was in a good spot, near where the Atlantic Ocean met four rivers: the Saco River, the York River, the Kennebunk River, and the Piscataqua River. It also had a deep harbor that made it the best place for ships from other ports, like Boston or even England, to stop.

Caption:

John Mason was an English investor who gave New Hampshire its name. A naval officer and businessman, Mason had been the governor of the British settlement of Newfoundland, on the coast of Canada. He realized how important the fur trade was, so he started a company based in New Hampshire to supply beaver furs for sale in England. The business was called the Laconia Company. Mason sent English settlers to build outposts along the Piscataqua River and the other rivers around what is now Portsmouth. Mason named this area New Hampshire after Hampshire County, where he lived in England. Mason was planning to move to New Hampshire, but he died before he could leave England.

Caption:

The Jackson House is the oldest surviving house in New Hampshire. It was built in Portsmouth around 1664 by Richard Jackson. Jackson was a woodworker, farmer, and sailor. The house was originally smaller than shown in this photograph. As time went on, later owners built additions onto it. The Jackson House is a National Historic Landmark and is owned and operated by Historic New England, so you can visit it in person if you are in Portsmouth!

Caption:

Many of the early settlers in Portsmouth, one of New Hampshire's first four English towns, were merchants. Merchants are people who buy and sell items to make money. Colonial merchants bought natural resources, like furs, fish, or mast trees from people who lived further inland. Sometimes they traded with the Native Americans too. Then they sold those items to other people, who shipped them all over the world. As merchants became more successful, they could buy their own ships and sell the goods all over the world themselves. As colonial settlements grew larger and larger, some merchants also opened their own shops to sell goods to other colonists.Many of the people who lived in Strawbery Banke became merchants. They would buy natural resources, like beaver pelts, fish, or mast trees, from people who lived further inland and then sell those items to people who shipped them to other places in the world. Some of the merchants even owned their own ships and made money by selling goods throughout America and Europe.

Caption:

This painting is a view of Portsmouth across the Piscataqua River during the time of the American Revolution.Strawbery Banke grew very quickly, especially as many of the merchants who lived there made a lot of money. They built big houses, churches, a meeting house, and warehouses to store all the goods they were buying and selling.

John Mason planned to move there and ordered that a large house be built for him and his family. Unfortunately, he died before he could leave England and never saw New Hampshire.

Strawbery Banke became the largest town in New Hampshire, and in 1653 it changed its name to Portsmouth. The new name was a tribute to John Mason, who had lived in Portsmouth, England.

Hampton

South of Portsmouth and slightly inland was the community of Hampton. The people who settled at Hampton were English, but most of them had lived in Massachusetts before they came to New Hampshire. The colonial government in Massachusetts wanted to expand how much land Massachusetts controlled, so it encouraged people from Massachusetts to move to New Hampshire and build a new settlement.

These colonists from Massachusetts formed a community at Hampton in 1638, although the settlement was originally called Winnacunnet, which was based on an Abenaki word. Many more people from Massachusetts moved to Hampton in the 17th century. The people of Hampton were mostly fishermen and farmers. They kept close ties to the people of Massachusetts.

Caption:

This is a smaller piece (known as a detail) of a historical map of Hampton, one of New Hampshire's first four English towns. It shows the part of Hampton that was the original settlement, founded in 1638. The map was made in 1938 to celebrate Hampton's 300th anniversary.Exeter

The furthest inland of all four English communities was Exeter.

The 200 people who settled there in 1638 were also from Massachusetts, but they didn’t get along with the government in Massachusetts very well. People in Massachusetts had to follow a lot more laws than the people in New Hampshire did, especially about religion. The Exeter settlers were looking for more freedom to practice their religion than the Massachusetts government would allow.

The leader of this community was a minister named John Wheelwright.

Caption:

John Wheelwright was an English minister who founded the town of Exeter, New Hampshire. In 1636, he emigrated with his family to Boston and began to preach there. He didn’t get along with the colonial authorities in Massachusetts Bay, though. They disagreed about religion, and the Massachusetts officials didn’t like what Wheelwright was preaching. Eventually he was banished from Massachusetts. Wheelwright, his family, and about 20 other families moved north to New Hampshire in 1638. They signed a deed, or a document, with the local Abenaki sachem, Wehanownowit, to buy a piece of land and build a town. They called the town Squamscott. Later it was called Exeter. Finally, the government of Massachusetts Bay pardoned Wheelwright, so he was able to go back to Massachusetts to live. Even though Wheelwright had left Exeter, the settlement was very successful and continued to grow.

Caption:

John Wheelwright was an English minister who founded the town of Exeter, New Hampshire. He emigrated with his family to Boston and began to preach. He didn't get along with the authorities in Massachusetts, though. They disagreed about religion. Eventually the Massachusetts authorities banished Wheelwright from their colony. Wheelwright, his family, and about 20 other families moved north into New Hampshire. They called their settlement Squamscott, after the Abenaki band that lived there. Later the town's name was changed to Exeter.

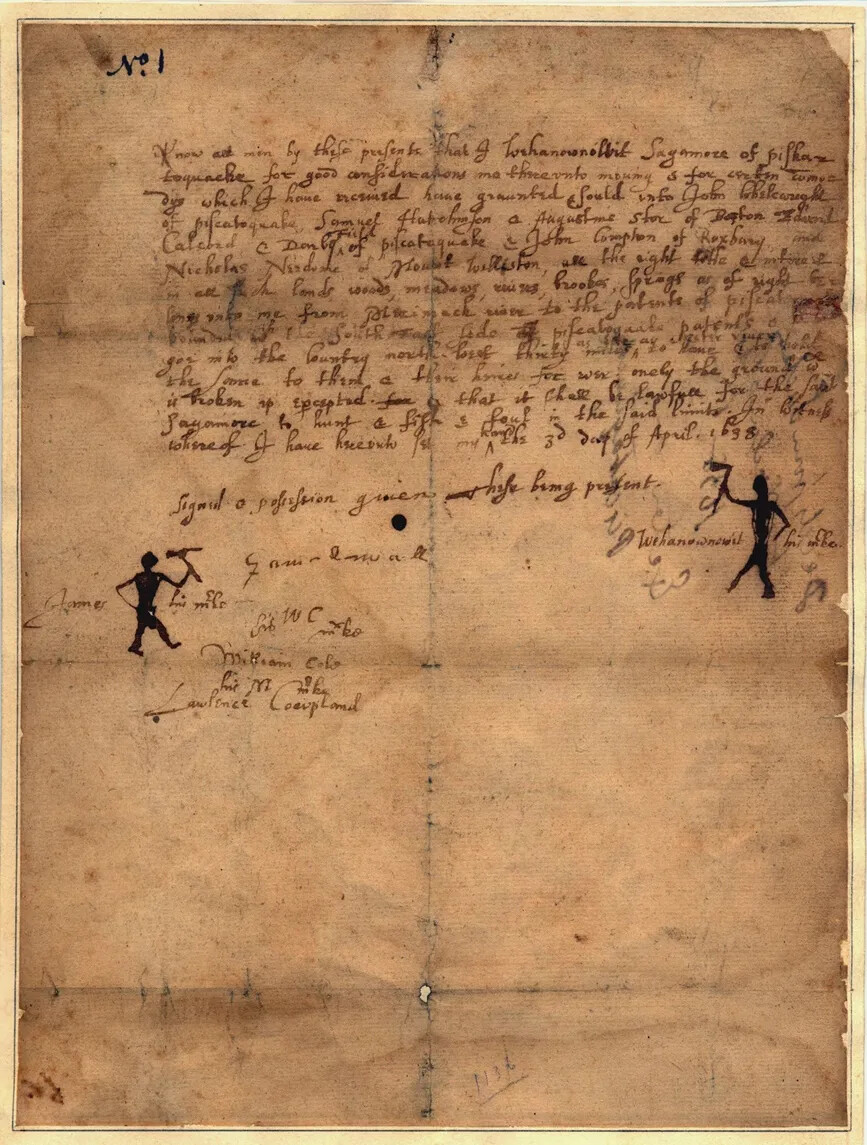

Caption:

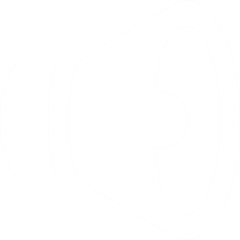

John Wheelwright was an English settler. Wehanownowit was the leader of the Piscataqua group of Abenaki people who lived in the Piscataqua River area of the New Hampshire seacoast. In the spring of 1638, Wheelwright and Wehanownowit signed this legal document, called a deed, so that the English could settle on the land where the Abenaki lived. This eventually became the town of Exeter. The English and the Abenaki had very different ideas about how to use land, so the two groups did not interpret this document the same way.There were more Abenaki who lived in this area of New Hampshire than where the other English settlements were. The hadn’t hit the Abenaki in the area around Exeter as hard as it hit those who lived on the seacoast.

Wheelwright didn’t want any conflict with the Abenaki who lived near the new settlement. He made an agreement with the Abenaki sachem, Wehanownowit, to buy a piece of land so the English could build a town. Wheelwright wrote out a deed for the purchase of the land, and Wehanownowit signed his name by drawing a figure that represented him. The English and the Abenaki had different ideas about what the deed meant, though. The English thought the deed gave them ownership of the land and everything on it. The Abenaki thought it meant they would share the natural resources found on the land and that their communities would work together.

Exeter quickly grew to be the second largest community in New Hampshire. Most of the people who lived there were farmers.

Caption:

Wehanownowit was the sachem of the Squamscott people, a band of Abenaki. During the summers, the Squamscott lived and farmed in the area around where the Squamscott and Exeter rivers meet. Several different bands of Abenaki used to meet in this area to fish for salmon. Unfortunately we do not have a lot of information about Wehanownowit, like when he was born and when he died. We do know that when John Wheelwright and his followers settled in the area where the Squamscott people lived, they wrote a deed, or legal document. The deed gave the English settlers the right to settle the land. It also said that the Squamscott people still had the right to hunt and fish there. Because he was the sachem, Wehanownowit signed the deed on behalf of the Squamscott people. He used a pictograph, or drawing of himself. We don’t know for sure what happened to Wehanownowit after the deed was signed. More and more settlers came to the town, which was eventually called Exeter. It was harder and harder for the Squamscott people to hunt and fish there. Wehanownowit and his people probably moved west to New York.Let's Review!

What are the big ideas in this section?

Dover

There were four settlements in New Hampshire in the first 100 years. Dover is the oldest permanent settlement. In 1623, Edward and William Hilton started it on the Piscataqua River. In the 1640s it grew as people developed industries and farms.

Portsmouth

Portsmouth was originally called Strawbery Banke, and the town sits where the Atlantic Ocean meets four rivers. Because of this location many of the people who lived there became merchants. They would take items from New Hampshire and ship them to other places. They also brought goods from elsewhere in the world to the people of New Hampshire.

Hampton

English people from Massachusetts settled in 1638 in Hampton. People who lived there were mostly fisherman and farmers and were closely connected to Massachusetts.

Exeter

Exeter was further inland than the other three towns. It was settled in 1638 by people from Massachusetts. They were looking for religious tolerance. They had to work with the Abenaki to get land for their town and made an agreement with a local Abenaki leader. However, the Abenaki and the English did not have the same view of their agreement.

Government

How were the towns governed?

Each of the four towns had its own government run by the people of the town. These governments made all the decisions in each town.

There wasn’t a government for the colony of New Hampshire yet. Even the British government didn’t pay much attention to the English settlements in New Hampshire. Instead, each community was independent and could do what it wanted.

Sometimes the Massachusetts government tried to take charge of the New Hampshire towns, but the towns mostly ignored the Massachusetts officials.

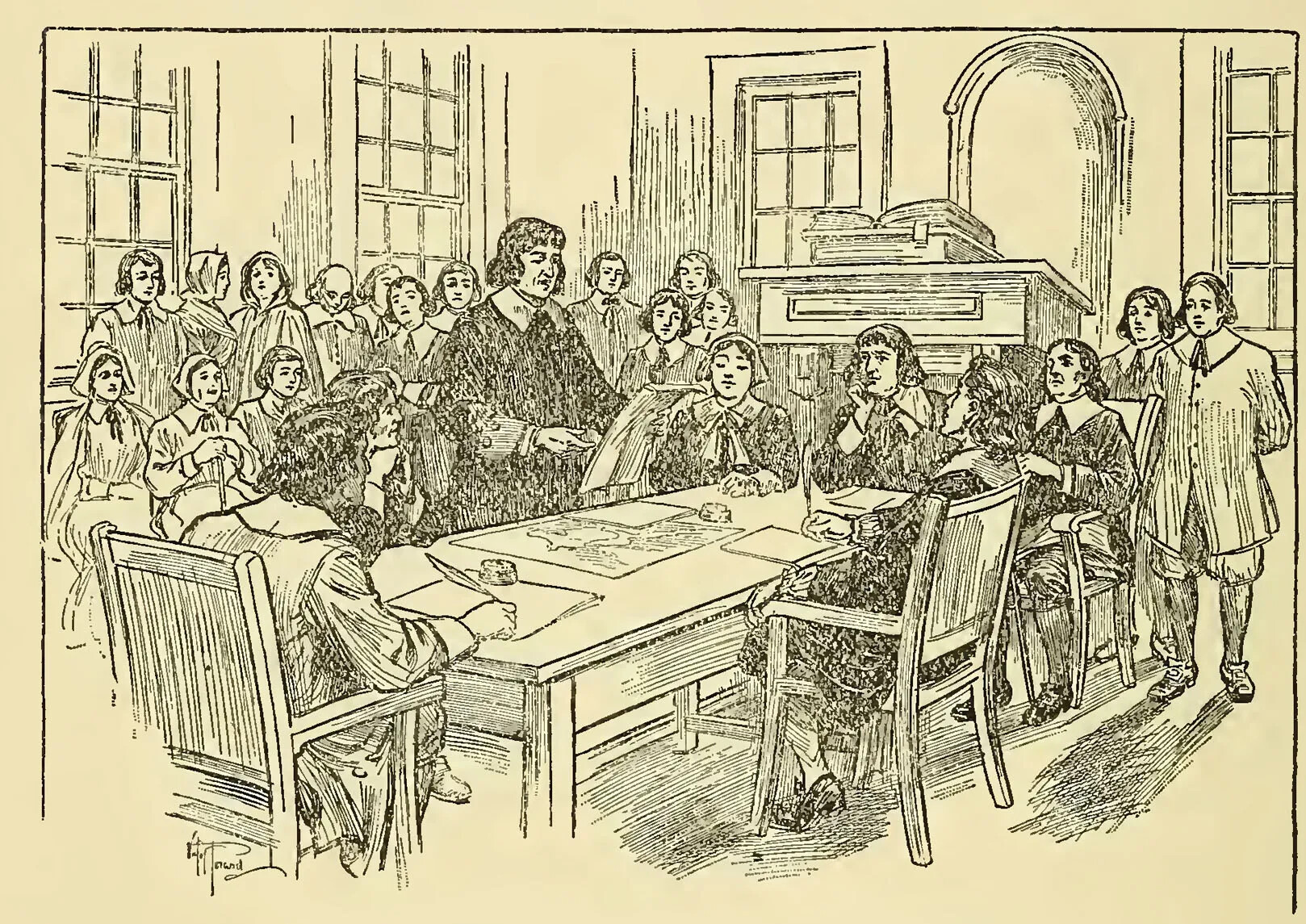

Caption:

New Hampshire's tradition of town meetings started in the 1630s. The townspeople would meet, sometimes as often as once a week, to discuss and vote on issues that were important to the town. For example, they would decide how to divide up the land, how much each person should pay in taxes, and where the farm animals were allowed to graze. All adult men who owned land could vote in town meeting. Women and enslaved people were not allowed to vote. Town meetings usually took place in the meeting house, which was also where church services were held.Church

Church was a very important part of life for most English settlers to New Hampshire. In fact, many of them left England and came to America because they wanted more freedom to practice their religion. In this early period of settlement, most towns only had one church, which was Protestant Christian.

The minister of a town’s church was a very important person. Most people looked up to him for his wisdom and experience. The church was the center of town life. The church helped the poor and the sick, as well as being the social center of the town. Most people went to church on Sundays and spent the entire day there listening to the minister’s sermons. He usually preached one in the morning and another one in the afternoon.

A town’s church and its government were two different things, but they often worked together to provide leadership for a community.

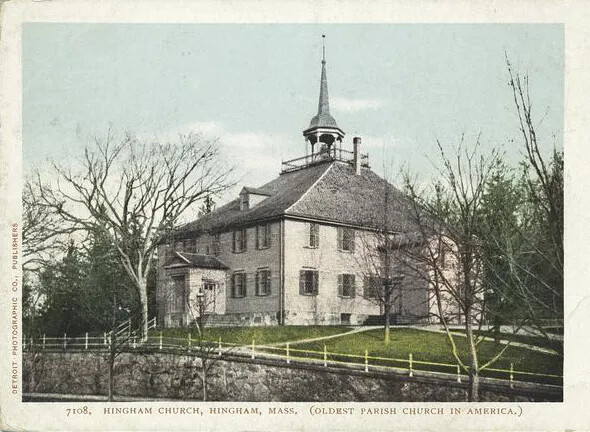

Caption:

Church was a very important part of life for most English settlers in New England, including New Hampshire. This postcard shows Old Ship Church in Hingham, Massachusetts. It was built in 1681 and is the oldest church building continuously used as a church in the United States.Schools

Starting in the 1640s, New Hampshire communities had schools for children so they could learn how to read and write and do simple math. But schools did not meet every day as children had so much work to do on the farms.

Schools were mostly for boys. Girls attended school to learn the basics of how to read and write, but many people thought girls would learn most of what they needed to know at home from their mothers.

Caption:

New Hampshire communities established schools for children starting in the 1640s. It was important to the settlers that children learn to read, write, and do simple math. Children did not attend school every day because they usually had a lot of chores to do on the farms.Farming

How did most people earn their living in these early New Hampshire communities?

Many people worked in those three main industries that were so important to early New Hampshire: fishing, furs, and forests. But there was a fourth industry that almost everyone worked in—farming.

All the English immigrants who came to New Hampshire had to produce their own food. Nearly everyone hunted animals like deer, fox, or rabbit to eat. Vegetable gardens were very common too, even in larger towns like Portsmouth.

Most people in New Hampshire farmed their land to produce food to eat and to trade with others for things they could not produce themselves.

Caption:

Almost every English settler in New Hampshire grew some crops, even if they also worked in other industries. They needed to grow food to eat as well as trade with others. They grew wheat, corn, and barley, vegetables like beans and squash, and also had apple orchards.

Caption:

Most English settlers in New Hampshire had to farm to produce their own food. If they had extra crops, they traded them with other people for the things they couldn't produce themselves.What did farms produce in colonial New Hampshire?

Farming in New Hampshire was very hard. Many crops did not do well in New Hampshire’s rocky soil. And there were so many rocks! Farmers had to dig up hundreds of thousands of rocks and move them out of the way to clear their fields for planting.

The growing season was also very short in New Hampshire compared to other places in America, especially further south. With a short growing season, crops did not grow very big or produce very much. Weather was a constant concern for farmers, as they needed just the right conditions to grow things. Too much water or not enough water could destroy the crops. A windstorm or ice storm could damage the crops as well.

Farming in New Hampshire was known as subsistence farming because New Hampshire farms produced just enough to allow people to subsist, or survive.

New Hampshire farms also produced many different types of crops. Farmers grew crops like wheat, corn, or barley. They also adopted the Abenaki practice of growing the “three sisters,” which was corn, beans, and squash all tangled up together.

Caption:

The Abenaki used a farming technique known as the "three sisters." They planted squash, corn, and beans together. The corn grew straight and tall, and the bean vines grew up around the corn stalks for support. The squash grew at the base of the corn stalks, and its big leaves helped prevent weeds from growing.

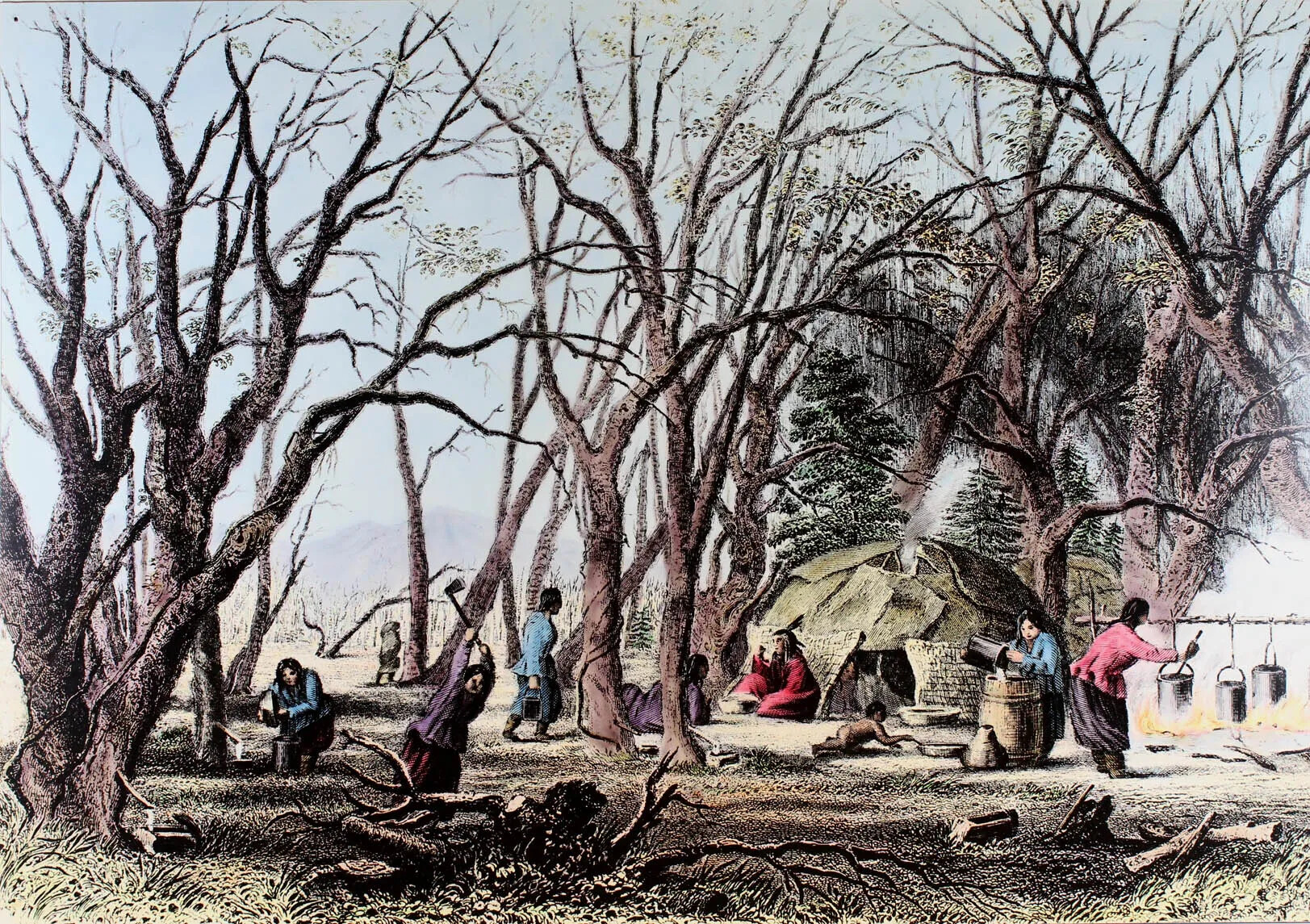

Caption:

The Abenaki learned how to collect sap from sugar maple trees to make maple syrup and maple sugar. The Abenaki believe that the sweet maple sap is a gift from the Creator. They also believe that Gluskabe changed the sap so that it only flows once a year and has to be boiled down. They used buckets made of birch bark to collect the sap and boiled it in clay pots. Maple syrup season is in the very early spring, so the Abenaki would camp at a site with a lot of sugar maples and produce the sugar and syrup, like in this picture. When the English arrived in the early 1600s, the Abenaki shared this knowledge with them. Today New Hampshire is still famous for its maple syrup. This is an illustration from a book printed in the 1800s.They had orchards that produced apples, which did well in New Hampshire. They gathered berries and nuts, just like the Abenaki did.

They raised livestock like cows, sheep, and goats, which produced milk so the farmers could make dairy products like cheese and butter. The livestock also provided leather for shoes and clothing, and the animals could be killed to produce meat. The fleece from sheep was used to make thread that was woven into cloth that was used for clothing and bedding. They also raised chickens, who laid eggs, which was an important source of food.

They tapped trees in the late winter to produce maple syrup once the Abenaki showed them how to do it.

They also had to chop wood to keep the fires going for cooking and heating.

Caption:

This book illustration shows what a colonial farm would have looked like in the 1760s.Farmers tried to produce everything they needed to live right there on their farms. Every member of a family had to learn helpful skills and crafts.

Women not only took care of the children and did all the cooking, but they made soap and candles, and turned fleece into thread and cloth so they could make clothing.

Men hunted and fished, made tools and other farm equipment, built structures on the farm like barns, sheds, or chicken coops, and usually had other crafts or skills, like making shoes or furniture.

Children worked alongside their parents in all these tasks and helped watch over their younger siblings. And everyone took care of the animals and tended to the crops and the gardens.

For most people living on farms, the day-to-day work kept them too busy to do anything else except go to church once a week and attend a few community events, like town meetings or weddings.

Neighbors helped each other when they could, and members of a town would work for the community sometimes, doing things like building a bridge or a meeting house.

Caption:

The Danville Meeting House was built in 1755. A meeting house is a building for gathering for town meetings, worship, and school. It was a very important building in a colonial settlement. Usually it was the first public building in a settlement. The meeting house in this photo was built so that the people in Danville (then called Hawke) did not have to travel all the way to Kingston to go to church or attend town meetings. Other meeting houses have had additions or renovations over the years, but this one looks very much like it did when it was built.Unsettled Government

How did New Hampshire become a British colony?

For most of the 17th century, the New Hampshire towns governed themselves without any kind of government that united all of them. Massachusetts often tried to claim that the New Hampshire towns were part of that colony, but most people in New Hampshire ignored them. For a while in the 1670s, though, the New Hampshire settlements officially became part of Massachusetts as Norfolk County.

In 1679, the British government decided that the New Hampshire towns should be their own colony with their own government overseeing all of them. The British government recognized New Hampshire as a separate colony from Massachusetts. By that time, there were about 2,000 English people living in New Hampshire.

Caption:

New England colonies had a strong tradition of self-government. That means that they made their own decisions about laws to follow. This image shows the Pilgrims from the Plymouth colony in Massachusetts signing a document called the Mayflower Compact. They agreed to make laws that were fair and just, and to follow them. New Hampshire's colonists also made their own laws. They elected representatives to the colonial legislature, which was called the Assembly. The Assembly made laws about taxes and how people should behave in public. Any adult male who owned property could vote for representatives to the Assembly.Once New Hampshire was separate from Massachusetts, it needed its own government. It had grown too big not to have a colonial government for all the people living there.

In 1680, the people of New Hampshire elected representatives for its first colonial legislature, which was called the Assembly. New Hampshire still had a lot of ties to Massachusetts, though. In fact, the two colonies shared the same governor, who was appointed by the British government.

Caption:

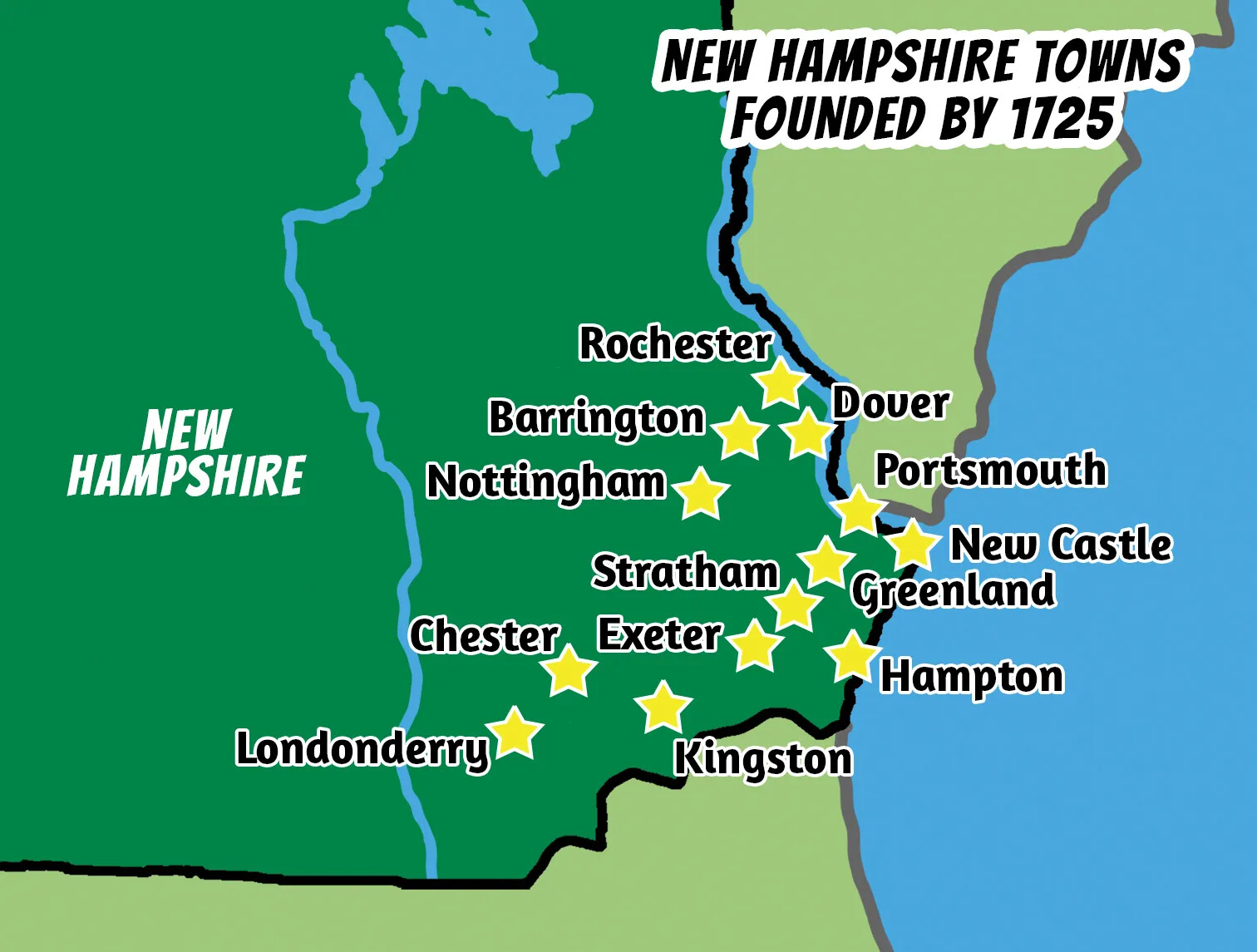

Simon Bradstreet was the governor of both Massachusetts and New Hampshire in 1680, when New Hampshire formed its own colonial legislature. He didn't pay much attention to New Hampshire, though. Instead, he let the New Hampshire Assembly govern the people of the colony.By the early 1700s, the people of New Hampshire were ready to expand their colony. They had settlements spread throughout southeastern New Hampshire. They had industries that allowed people to earn money and drew more people to New Hampshire. They had a government that the people of New Hampshire had a say in running. And they were part of the British Empire, which had many colonies in North America.

Caption:

This map shows the New Hampshire towns founded by English settlers in the early colonial period, up to 1725.Let's Review!

What are the big ideas in this section?

Government, Church, and Schools

Each of the four towns had its own government run by the people of the town, and the church was also very important in their lives. During this time, New Hampshire communities also began to have schools, although they were mostly for boys.

Farming

Farming in New Hampshire was called subsistence farming. New Hampshire was not a very easy place to grow crops. To survive, farmers learned from the Abenaki, raised livestock, and grew what they could, like wheat, fruit trees, or the “three sisters.” Farming families worked hard to produce everything right on their farms that they needed to survive.

A British Colony

During the 17th century, the New Hampshire towns governed themselves separately, although the people of Massachusetts did try to claim the towns as part of their colony. In 1679 the British government recognized New Hampshire as its own colony. In 1680 the people of New Hampshire elected representatives for its first colonial legislature.

Looking Forward

By the early 1700s New Hampshire was established and looking to expand. It had settlements, industries, and a government. It was part of the British Empire and was one of the British colonies in North America.

Conflict between Cultures

How did the relationship between the Abenaki and the English change in the late 1600s?

In the 1660s and 1670s, the Abenaki and the English started to clash more. Passaconaway, who was a very old man by then, stopped guiding his people and turned leadership over to his son Wonalancet and his grandson, Kancamagus.

Wonalancet tried to keep the peace between the Abenaki and the English, but Kancamagus was very unhappy with the way the English treated the Abenaki. There were many English settlers in New Hampshire by then, and Kancamagus realized that there would soon be more English than Abenaki in New Hampshire.

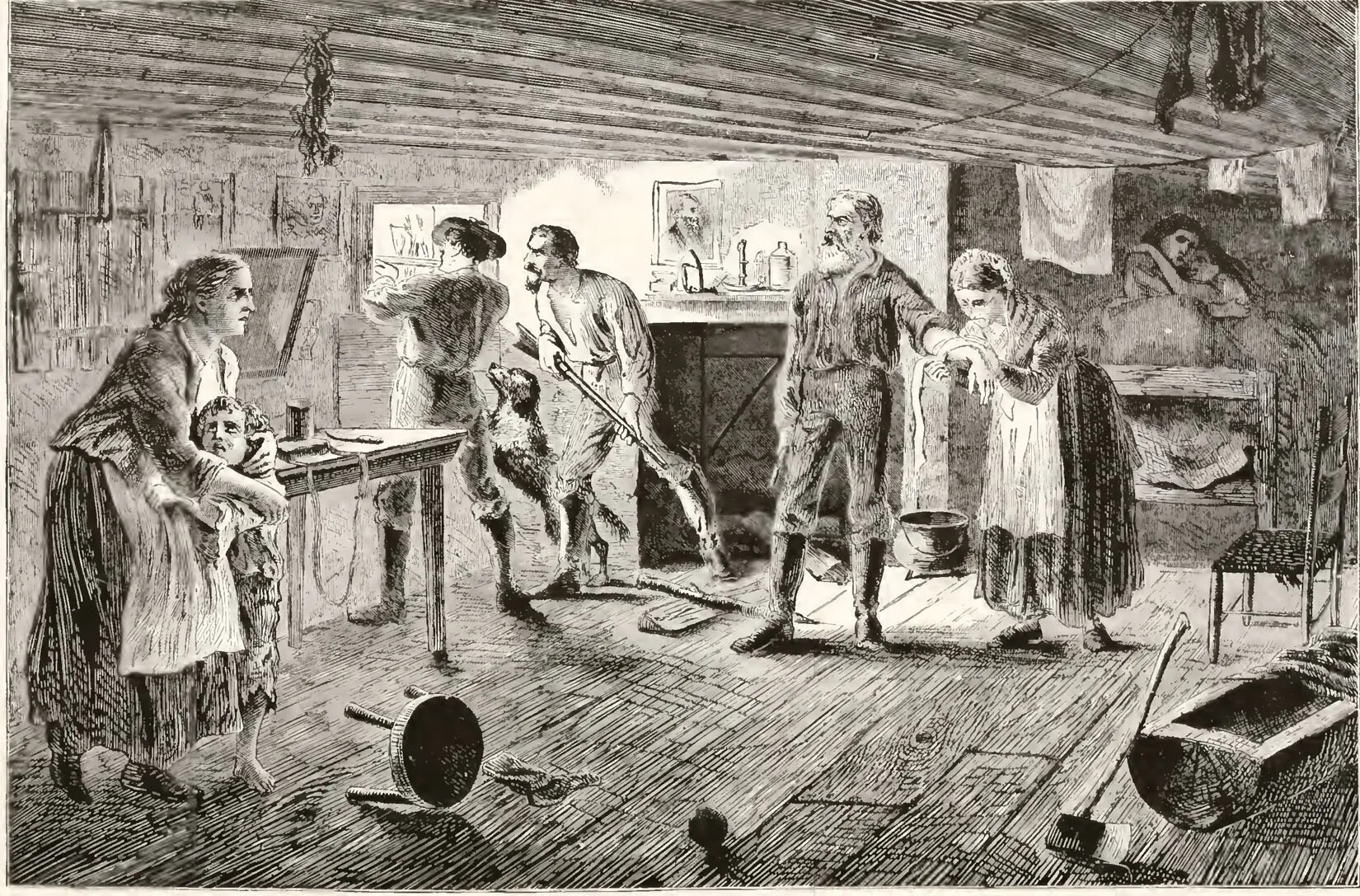

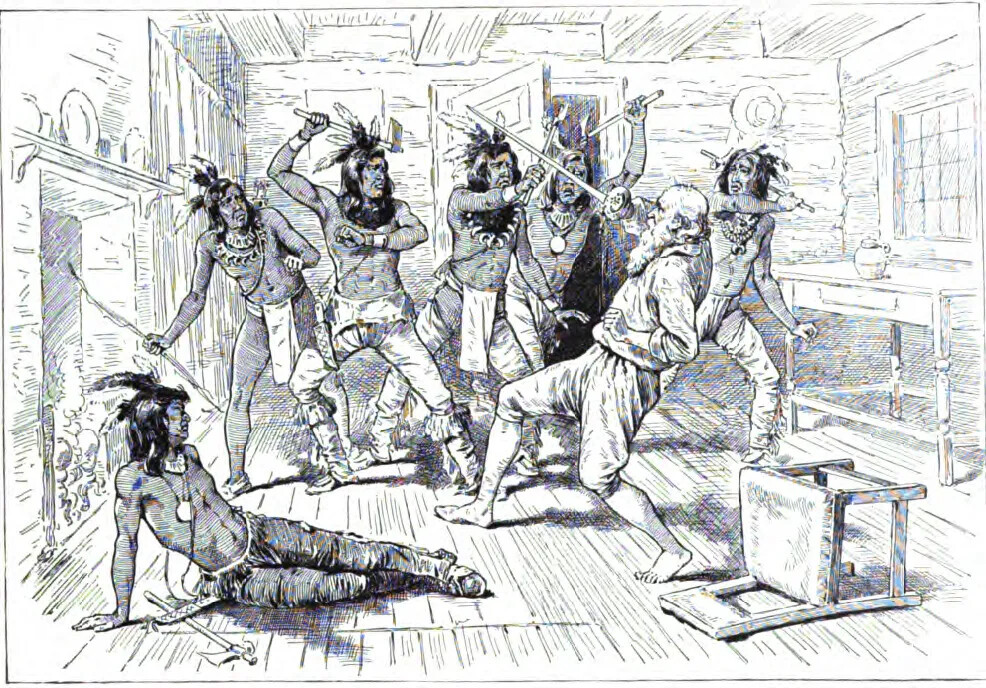

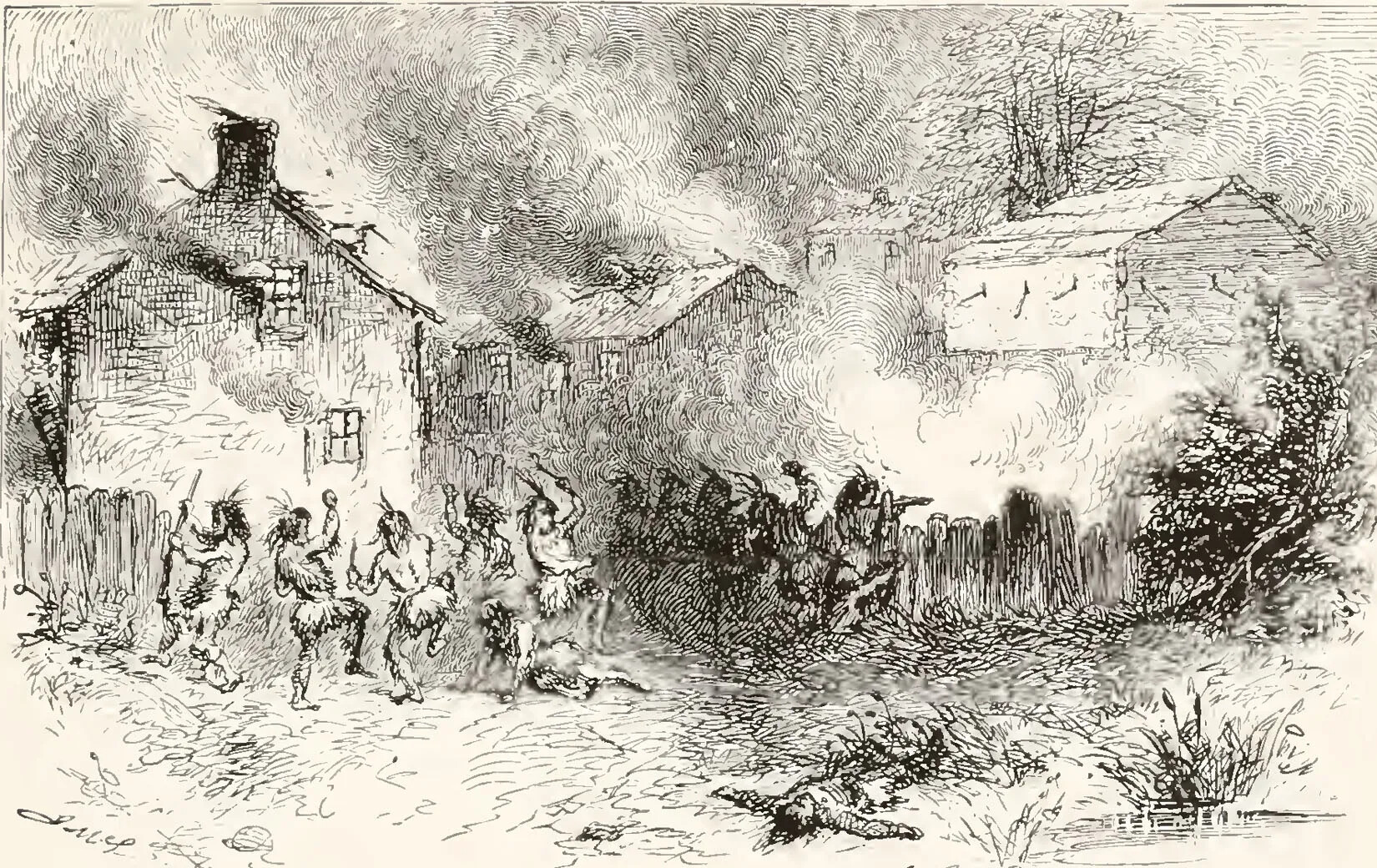

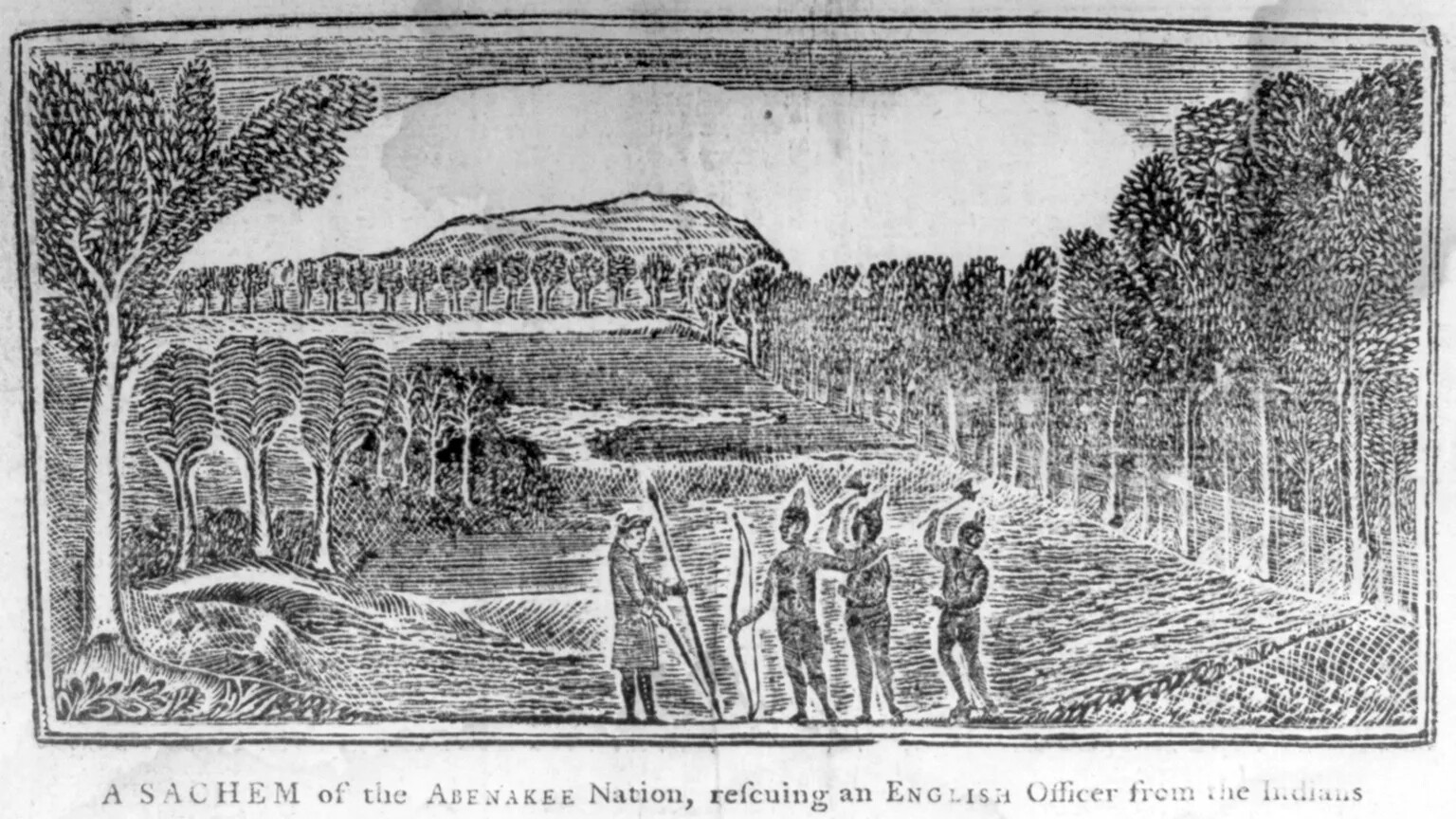

Caption: